WORDS: ELLIOTT HUGHES | PHOTOS: CHOPARD, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, PORSCHE, MERCEDES-BENZ

“I never dreamed of becoming a racing driver. In the beginning, I wanted to be a gardener,” recalls Jacky Ickx. Written down, such a sentence could easily be a joke, particularly when the person saying it is a six-time Le Mans winner, Can-Am champion, Formula 1 World Championship runner-up, two-time World Endurance champion, and Paris-Dakar rally winner. Yet I can tell from Jacky’s tone and expression that he is deadly serious.

I’m sitting with the Belgian motor sport legend in the New Bond Street flagship store of watchmaker Chopard, for whom he has long served as a brand ambassador. The sun is shining, and soon Jacky will be speaking on stage at Concours on Savile Row, just around the corner. Reclined on a sofa in the London premises, he is relaxed, warm and engaging.

“I was a poor student with a limited attention span, and at school I used to sit at the back of the class and stare out of the window. My parents felt very embarrassed that I had no idea what I wanted to do in life,” Jacky confesses. “My teacher would say: ‘Your son is very intelligent but so lazy that we can’t do anything with him.'”

Ironically, his reluctant approach to academia inadvertently helped propel him to motor sport stardom. “To encourage me at school, my parents gave me the lovely gift of a 50cc motorcycle. I started doing trials, and discovered that I wasn’t finishing last any more – and that I wasn’t as bad as my teacher thought I was. The smell of victory drew me in.”

In Jacky’s case, the whiff of success proved irresistibly intoxicating as he swept up silverware across an impressively diverse range of disciplines. Racing drivers aren’t generally renowned for their humility, yet Jacky continues to defy expectations as I ask him to recount a few of his many past triumphs:

“I had plenty of victories, yet victories mean nothing if you don’t appreciate the fact that the car or motorcycle is built by passionate people who love what they do yet work in the shade. It’s so much easier to win when the car is easy to drive and comfortable. So, when you are on the podium, you steal the spotlight from those you never see. You are the mirror of those who made it possible.”

Jacky’s humble and philosophical thinking is almost disarming for a driver of his calibre. Yet it starts to make sense when you consider the fact that some of his most prolific successes came in the Le Mans 24 Hours, a race in which teamwork is paramount.

“In long-distance racing, you have to work with your team-mates, so it’s no longer about ‘me, myself, and I’. Instead, it’s about ‘us’,” he smiles. Perhaps that’s why both Jacky and Sir Stirling Moss are often considered the greatest drivers to never win an F1 World Championship; you can argue that for gentlemen such as them, chivalry came at the expense of maximising results.

A prime example of this in Jacky’s F1 career came in 1970, when he came so agonisingly close to becoming World Champion with Ferrari. The title was posthumously awarded to Jochen Rindt, who was tragically killed in his Lotus 72 during practice for the Italian Grand Prix. For his part, Jacky is adamant that the title was Jochen’s and that he’s glad he didn’t take it because it “wouldn’t have felt right to have won in those circumstances”.

Clearly, drivers of Jacky’s generation had to contend with a tragic level of danger that is thankfully inconceivable in modern forms of motor sport. But he also explains that it was the perfect time for a racing polymath such as him.

“Back then, everybody was competing in every form of car racing. You could race at Crystal Palace in Formula 2, then go and race Cortinas at Oulton Park with Jim Clark and Jack Brabham in the British Saloon Car Championship. We were professional mercenaries.

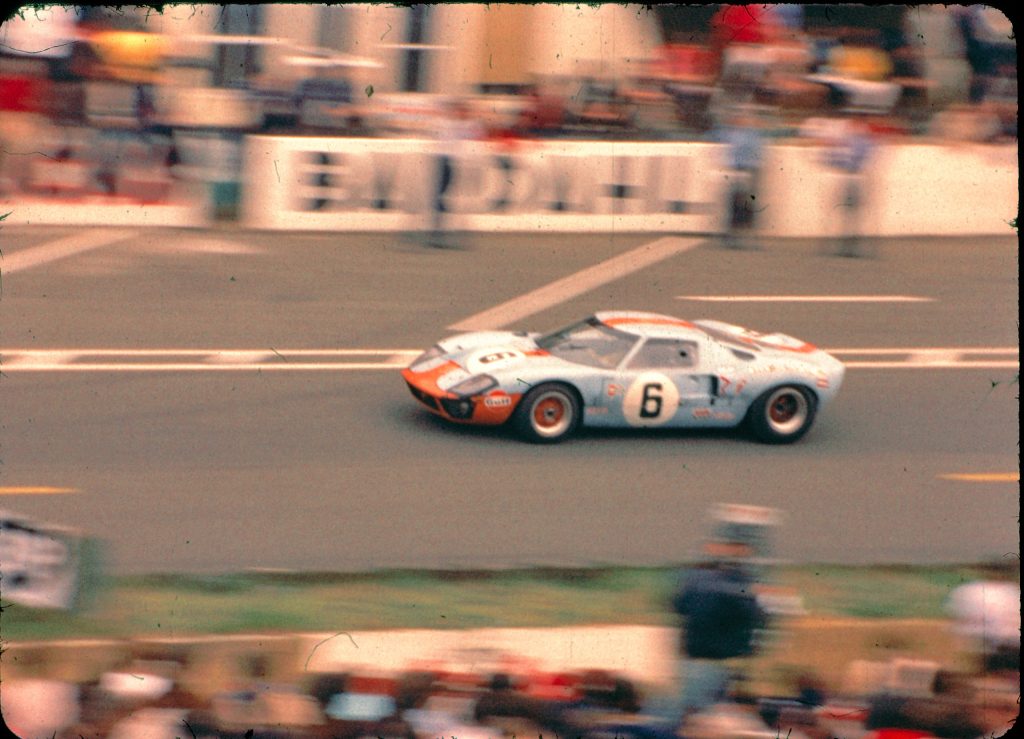

“In 1968 I was driving for Ferrari in F1, and I was doing endurance races at the same time, and then I won Le Mans in 1969. This era does not exist any more, so the sort of statistics I have will never be reached in the future because modern drivers focus on only one discipline.”

The recent endeavours of Fernando Alonso have drawn parallels to the versatile drivers of yesteryear. Alonso, while taking a break from Formula 1, achieved victory at Le Mans with Toyota, competed in the Indy 500 and ran in the Dakar Rally.

In contrast, the Dakar Rally holds far greater significance in Jacky’s career. While he secured victory in the arduous race in 1983 for Mercedes-Benz, it is his campaigns with Porsche, driving the iconic Rothmans-liveried 959, that most people associate with him in Dakar Rally lore.

“For me, the Paris-Dakar is the hardest race you can do. It’s between 10,000km and 14,000km, and most of it is a special stage. There’s no traffic lights, no signs, there’s nothing. Just small tracks in the sand,” he explains.

Philosophical as ever, it isn’t the challenge of the race or the taste of victory that Jacky found so rewarding about running motor sport’s most punishing gauntlet: “You discover another aspect of the world. You see another continent, and you discover other humans with such a different way of life who are in a different type of fight to survive.

“Dakar allowed me to separate myself from just racing, racing, racing and winning, winning, winning. It allows you to see everything, when before you’re almost blind. When you go into the desert, you come back down to earth, you realise your value as a single human being on this planet when you’re in such emptiness. That’s why Dakar is so valuable.”

In this line of work, it’s not unusual for top racing drivers to be tricky to interview. Yet Jacky is the total opposite; he’s friendly, enigmatic and fascinating to listen to. When he said at the start of our conversation that he “never planned to be a racing driver”, it seemed tricky to believe. Once our interview ended, however, it’s much easier to see why. Gardening’s loss.