WORDS: RICHARD HESELTINE | PHOTOS: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, JAGUAR, AUDI, TOYOTA, FERRARI

The momentous 100th year of the Le Mans 24 Hours gets underway this weekend. To celebrate, we’re sharing the top ten from our Top 50 Le Mans Moments feature, from Magneto issue 11.

10: LEVEGH’S HEROICS

His name is forever associated with the 1955 Le Mans inferno, but ‘Pierre Levegh’ (Pierre Bouillin) merited more. His efforts in 1952 deserve veneration, not least because he came close to being the only solo victor in the race’s history. A year earlier, he’d finished fourth with René Marchand, and in 1952 they fielded a Talbot-Lago T26C sports-racer.

The ’52 running was one of high attrition, and during the night he had a healthy four-lap lead over his Mercedes-Benz pursuers. He refused to yield to his team-mate, and appeared set for a fairytale win – only for the car to expire with just an hour left to run. At the time it was assumed that fatigue had set in; that he wrong-slotted, which prompted a massive over-rev. However, following his death in 1955, The Autocar reported that Levegh had become aware of a vibration emanating from the bottom end early on. Doubting Marchand’s mechanical sympathy, he opted to stay behind the wheel for the duration.

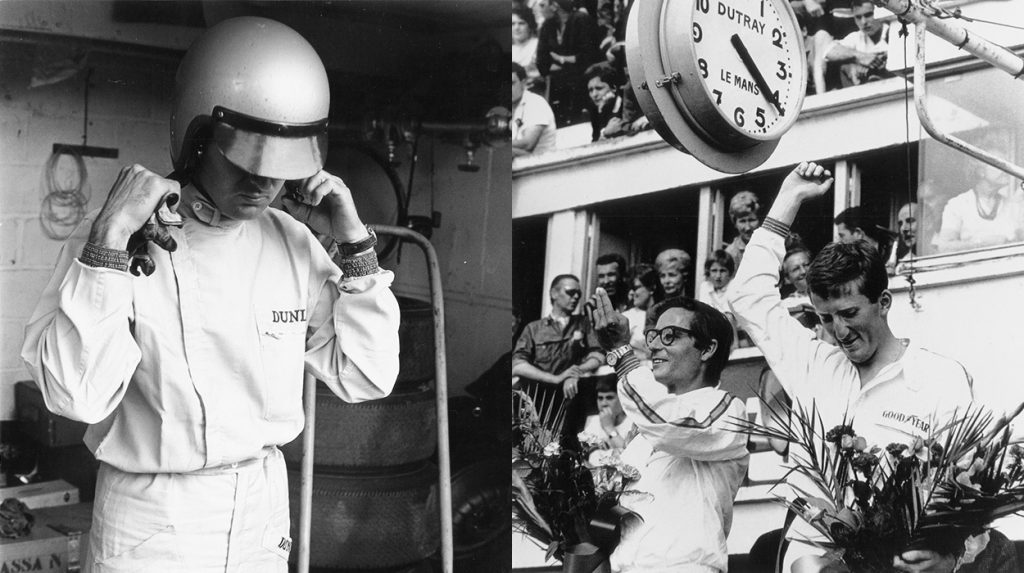

9: ICKX’S PROTEST

The 1969 event was full of memorable moments, not least Jacky Ickx’s slow saunter to his car at the start. A year earlier, Willy Mairesse had crashed on the opening tour while he attempted to close the door of his Ford GT40. Fellow Belgian, the mercurial Ickx, staged a one-man protest against the classic Le Mans sprint. He took his time doing up his belts, and his JW/Gulf GT40 was the last car away.

Porsche was tipped to win, and the Richard Attwood/Vic Elford 917 dominated much of the race. At one point, they held a five-lap advantage; however, the car dropped out on the Sunday morning. The GT40, which Ickx shared with Jackie Oliver (who tends be ignored whenever this race is discussed), assumed the lead. However, the final three hours descended into an epic battle between the blue-and-orange car and the works Porsche 908LH of Hans Hermann and Gérard Larrousse. Ickx and Hermann slipstreamed each other to the end with barely 120 metres separating them. It marked the first of six wins for Ickx.

8: PORSCHE WINS, FINALLY

You had to feel for Hans Hermann. The 1969 event in which he had come so close to winning was his 13th attempt; class honours were scant reward. In 1970, he was armed with a 917K and new team-mate Richard Attwood. Despite the language barrier, they gelled brilliantly, theirs being one of nine examples of the flat-12-engined monsters entered in the race (seven started). They were up against a legion of Ferrari 512s.

By midday on the Sunday, only 19 of the 51 starters were still running amid the murk. At the end, only seven were classified, with Hermann and Attwood having finished five laps clear of 917-mounted Gérard Larrousse and Willi Kauhsen. It wasn’t the most glamorous of endings, mind. Denis Jenkinson wrote in Motor Sport: “…The winners were put in the back of a sand-and-gravel lorry, and it set off on a lap of honour. It was actually a lap of dishonour, for the lorry looked like a dustcart setting off to pick up rubbish.” Hermann had promised his wife he would quit racing if he won. He kept his word.

7: MYTHICAL DRUNKEN ANTICS

The Jaguar C-type won first time out in 1951. However, the following year’s race was an embarrassing failure; the remodelled body resulted in chronic overheating and all three works entries retired. A year on, the much-developed C-type was armed with disc brakes (a Le Mans first), and a line-up of Duncan Hamilton/Tony Rolt, Peter Walker/Stirling Moss, and Ian Stewart/Peter Whitehead. However, an incident during practice led to one of the 24 Hours’ more colourful legends; that Hamilton and Rolt were suffering the ill effects of drink come the race.

All three Jags had dipped under the lap record during the build-up. However, the Hamilton/Rolt car had been on-track at the same time as the spare C-type, which happened to wear the same race number (Norman Dewis needed to qualify to act as reserve). Ferrari protested, a fine was levied, and Jaguar took the hit. Yet folklore has it that Hamilton and Rolt, believing they had been disqualified, drowned their sorrows – only to earn a reprieve. They won, of course, ahead of Walker and Moss, but the ‘driving under the influence’ bit is fiction.

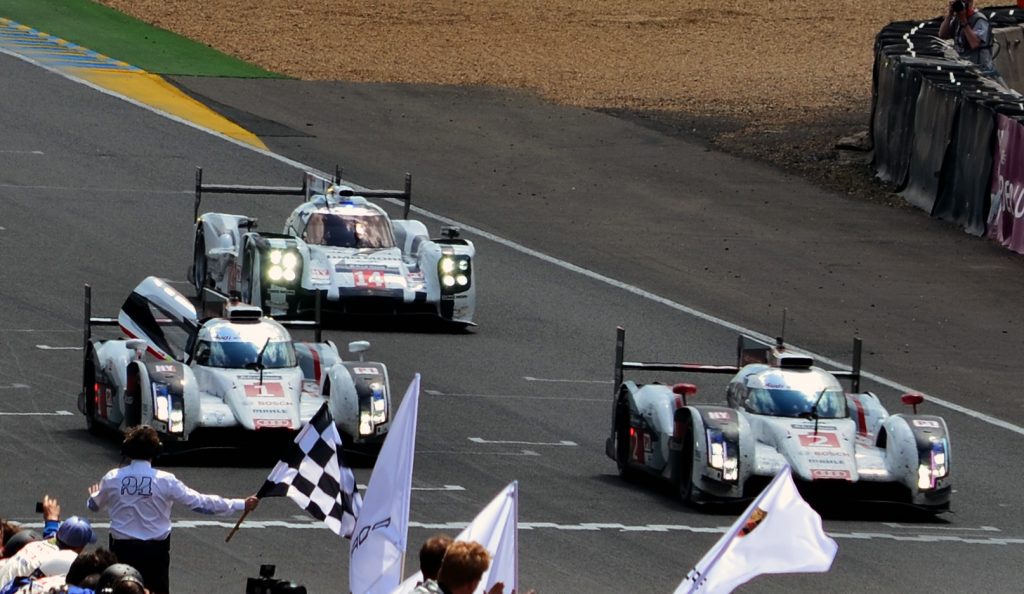

6: AUDI’S DOMINANCE

You have to feel for Audi. The problem with manufacturer involvement in motor racing is that they tend to be fickle; they’re likely to pull out at a moment’s notice. That is certainly true of the 24 Hours, but not for this resolutely German brand. True, for the first decade and a half of the new millennia, the identity of the winning marque seemed preordained; that it was simply a case of guessing which Audi was going to win. But you can’t blame it for the lack of competition – and it isn’t as though Audi had it easy all the time.

It didn’t need to go down the diesel route in 2006. It made life difficult for itself, but it was out to prove a point – and it did. And in 2008, Peugeot had the quicker car, and there was a scintillating inter-marque battle in the final hour, but ultimately it was the Audi’s stability in variable conditions that contributed to yet another win. All told, Audi won 13 times from 2000-14. It is now second only to Porsche in terms of victories.

5: TOM KRISTENSEN: THE KING OF LE MANS

Good fortune seemed to rain abundant on Tom Kristensen in the great race. The Dane won on his debut in 1997 driving a Joest Racing Porsche WSC-95 alongside Michele Alboreto and Stefan Johansson. Even then, he was a late substitute for an injured Davy Jones. He then drove for BMW in 1998-99, before claiming 2000-02 honours alongside Frank Biela and Emanuele Pirro with Audi.

A gap year with Bentley in 2003 resulted in another win, and the following June he equalled Jacky Ickx’s record of six victories aboard an Audi R8. In 2005, he claimed a seventh victory, and he then extended his tally in 2008. In 2013, he furthered his run with a ninth win, again with Audi, before calling time on driving after the following season. Kristensen made 18 starts at Le Mans and won 50 percent of the time. He also placed second twice (2012, 2014), and third three times (2006, 2009-10). He retired from the other four events. Records are meant to be broken, but we can’t see his being eclipsed any time soon.

4: LOCAL WINS RACE

In 1949, a three-year-old local boy looked on entranced as racing returned to Le Mans. He vowed that one day he’d win the 24 Hours. There were few early indicators that Jean Rondeau possessed any great skill as driver, though. In 1972, he raced a Chevron B21 in the 24 Hours alongside Brian Robinson. The car dropped out on the Sunday morning. A year later, there was a failure to qualify aboard an aged Porsche, and in 1974, he placed 19th – out of 20 finishers – in the same car. In 1975, his weapon of choice… a Mazda S124A (RX-3 in the UK).

However, he was nothing if not persuasive, and with considerable assistance from aerodynamicist Robert Choulet, Rondeau’s eight-man crew rocked up at Circuit de la Sarthe in June 1976 with two beautifully prepared cars (they were named in honour of the main sponsor Inaltera, which made wallpaper) and the cream of French driving talent. After a change of name to Rondeau, the team/constructor regrouped and, in 1980, the local boy with big dreams won alongside Jean-Pierre Jaussaud.

3: 1955 LE MANS TRAGEDY

It was a race that lives on in infamy. June 11, 1955 was – and remains – the darkest day in motor sport history. That year saw 83 race-goers killed and many multiples of that injured after Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes-Benz was launched into the crowd before disintegrating, fire raging through the spectator area sited across from the pits. The fallout was seismic, not least for those whose actions led to the catastrophe.

Levegh, whose breakdown at the last gasp in 1952 had gifted Mercedes-Benz a 1-2 finish, joined the works team for 1955. The 300SLR had already claimed honours elsewhere, not least in the Mille Miglia, and they were a threat from the outset. Star driver Juan Manuel Fangio (sharing an SLR with Stirling Moss) vied with Jaguar’s Mike Hawthorn during the early running, repeatedly swapping the lead and dipping below the lap record.

At 6:26pm, the accident occurred after the latter pitted. Hawthorn raised his hand to indicate his plans and pulled to the right. He braked hard, his D-type being equipped with discs. Lance Macklin swerved to avoid him, which placed his Austin- Healey 100S in the path of Levegh’s 300SLR. The Frenchman had nowhere to go, the British roadster acting as a launch ramp. Fangio, who was in close proximity, somehow missed the carnage, slightly brushing Hawthorn’s Jaguar that was by now stationary. Levegh’s charred body initially lay in full view on the pavement.

Mercedes-Benz withdrew from the event, much to the vocal annoyance of Moss, but the race wasn’t red-flagged. Instead, Hawthorn and team-mate Ivor Bueb emerged victorious. Recrimination was never far away thereafter, and Macklin brought a libel suit against Hawthorn following the release of the latter’s 1958 autobiography Challenge Me the Race, in which he effectively absolved himself of responsibility. It remained unresolved due to Hawthorn’s fatal road accident that same year.

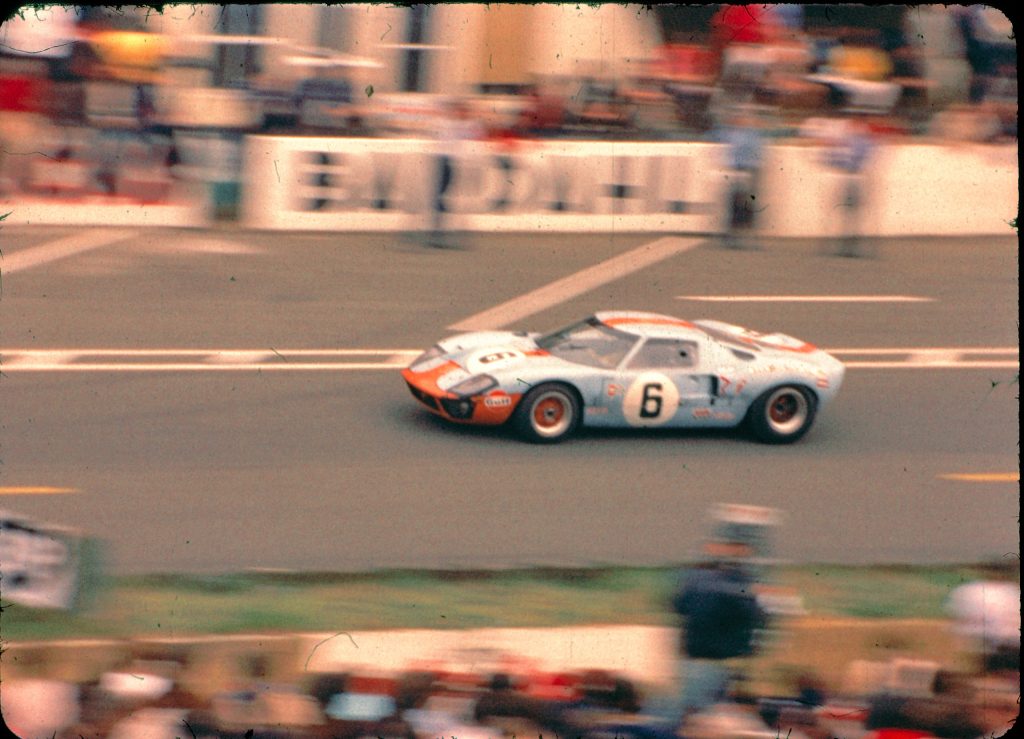

2: FORD V FERRARI

It was a battle for supremacy the likes of which had never been seen before. Henry Ford II, having been jilted at the altar by Enzo Ferrari, vowed revenge. He got it, too. However, the legend behind how the Blue Oval bested the Old Man is precisely that. It has been embellished beyond recognition in print, and reimagined by Hollywood to the point that it’s hard to differentiate the actual from the apocryphal. What is undoubtedly true is that victory for the Ford GT40 wasn’t the work of a moment.

Ford’s budget for its Le Mans bids, let alone the Total Performance programme as a whole, was astronomical. One insider likened it to that of the Moon Landing. Nevertheless, the first attempt at the 24 Hours in 1964 ended with retirement for all three cars. A year later, it was another washout. Then, in 1966, the 7.0-litre Mk2 scorched to victory with a staged close-formation 1-2-3 finish. It marked the end of Ferrari’s run at Le Mans, the Italian marque having won year after year since 1960. However, it is worth pointing out that Ferrari did sports cars, Formula 1 and various other disciplines, spending the sort of lira that wouldn’t cover Ford’s catering budget.

It is also worth recalling that while Ferrari got its bottom kicked on hallowed ground in 1966, it did return the favour at Daytona the following year. It finished 1-2-3 – but we have yet to see a film about that…

Joking aside, though, there is no denying the fact that Ford set itself a goal and achieved it. And how. The 1967 Le Mans race saw AJ Foyt and Dan Gurney win in the mighty Mk4, while JW Automotive/Gulf squad famously claimed honours in 1968-69 using the same GT40 (no. 1075). ‘The Deuce’ got his revenge on Il Commendatore. We should all be grateful that Enzo got his back up in the first place.

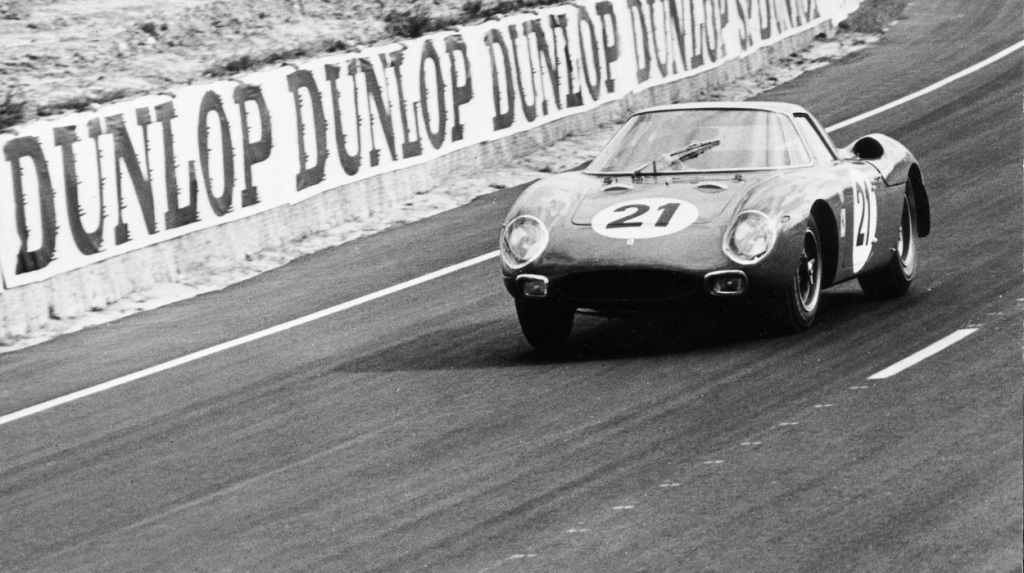

1: THE THIRD MAN

Oh, where to start? The 1965 Le Mans 24 Hour race has long since passed into legend. It’s a story of how a privateer squad upheld Ferrari’s honour while the works team fell apart, and Ford’s mega-money bid foundered. Even then, victory was only secured late in the day. The thing is, that is only the amuse-bouche to the big story; that a third, uncredited, driver got behind the wheel of the winning car for a stint. That, and the reasons why he was installed in it in the first place.

Predictably, the GT40 army led the charge come 4:00pm on June 19 of that year. It didn’t last long. Ferraris blanked the top six positions as darkness fell. By the early hours of Sunday morning, the 250LM entered by Luigi Chinetti’s NART squad, and shared by Jochen Rindt and Masten Gregory, was lying in a distant third place. By midday, just 14 of the 51 starters were still lapping, with the Franco-Belgian partnership of Pierre Dumay and Gustave Gosselin seemingly on target to take the win aboard their 250LM.

However, Rindt was lapping faster than Dumay in the NART 250LM that was now in second place. And then the leader’s luck took a tumble late in the day; Dumay somehow managed to control his car after it developed a puncture while travelling flat-chat down the Mulsanne Straight. Five laps were lost making repairs. There was no way the deficit could be clawed back, so Rindt and Gregory came home the victors, Chinetti adding a win as an entrant to the three he had accrued as a driver.

That would be a great story in itself, but the narrative surrounding how the race was won has since taken on a credibility-stretching life of its own. These days, reliability tends to be of the bulletproof variety. Way back when, cars tended to be nursed, coaxed and cajoled into completing the distance – and the 250LM’s transmission was notoriously fragile. Some state as gospel that Rindt and Gregory fully expected their car to retire early, so deliberately beat on it. Why flog your guts out and prolong the inevitable?

Somehow, though, it stayed together. Asked about this, Luigi Chinetti Jr, who was on site that year, said: “If dad thought for a moment that they were trying to break his car, he would have broken their asses.”

Additional intrigue surrounds claims made by NART regular Ed Hugus that he had picked up the slack during the night; that Gregory didn’t enjoy driving in the dark because he wore glasses, so Hugus took his place. His involvement was purportedly glossed over because it would have led to the car’s disqualification. His version of history has, astoundingly, been accepted as gospel truth in certain circles – and in print, too. However, there isn’t an iota of a scintilla of a nuisance of evidence to suggest that any of it is true.

A lack of proof doesn’t mean something didn’t happen. However, without corroboration you have to doubt the veracity of Hugus’s claim. But what is really telling isn’t so much that the 250LM triumphed at Le Mans in 1965, more that Ferrari hasn’t won there since. Given that the brand is set to field a new weapon in the hypercar class in 2023, maybe we won’t have to wait too much longer for outright win number ten.