Words: Nathan Chadwick | Photos: Heveningham Concours/AUDI

“That race really put me on the map,” reflects Allan McNish. “It opened the door to all that followed.”

A third place at Laguna Seca in 1997 might not seem like a stunning result in the Scotsman’s stellar career, which has seen three Le Mans 24 Hours victories, three American Le Mans series wins and triumph in the World Endurance Championship. However, back in 1996 Allan’s single-seater career had drifted into the doldrums. Yet in the space of two years, he’d claimed victory at the 1998 Le Mans 24 Hours.

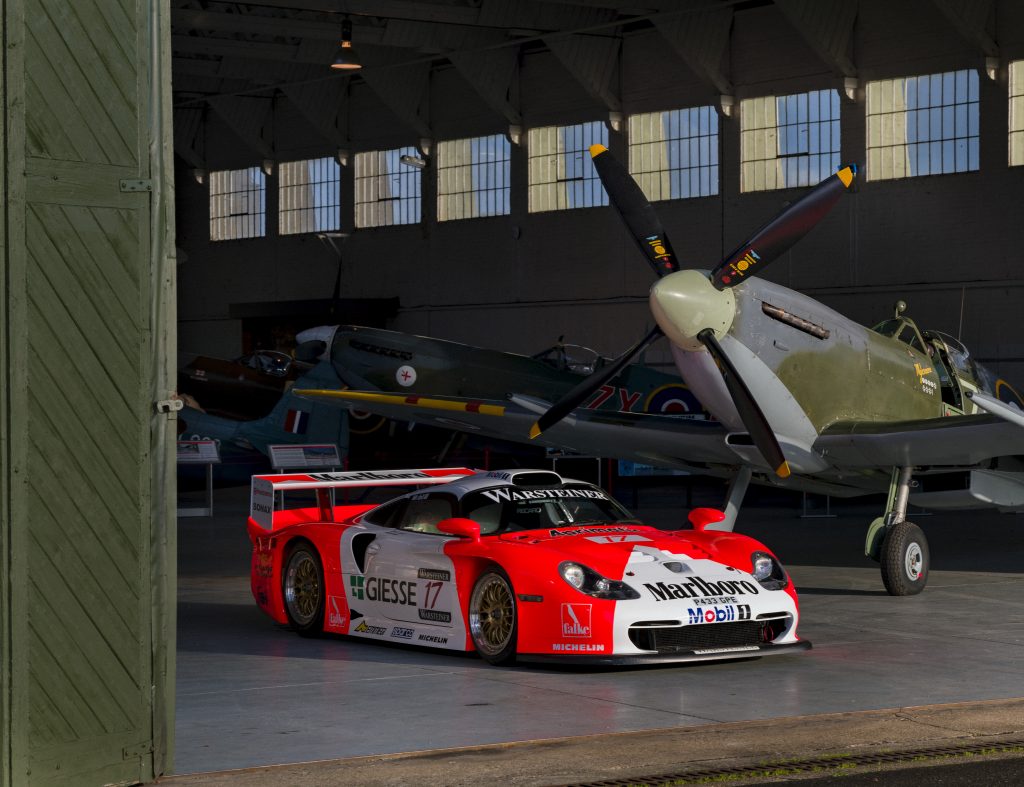

The key to it all was an appearance at the final round of the Mercedes-Benz-dominated 1997 FIA GT Championship in a Works-prepared Porsche 911 GT1 alongside Ralf Kelleners. That car, now sporting a different livery, will be appearing at the Heveningham Concours in Suffolk, UK on July 8-9, 2023.

Allan’s route to Porsche started in 1995, via Jost Capito, most recently the team principal of Williams F1. “He was running Porsche Supercup in 1995, and asked me if I would like a race; I couldn’t do it then because it clashed with an F3000 event, but I said yes, no problem, next year,” Allan remembers. “I did it the next year, at Silverstone – but it was the hardest thing I ever drove in my life, that bloody car!”

Jost and Allan kept in touch, and Allan’s name was repeatedly mentioned to Jost’s successors and, critically, Porsche Motorsport boss Herbert Ampferer, which led to two tests. “I wasn’t really sure about sportscar racing – I thought you drove at 50 percent, nursing it around like you’re driving to the shops – only a bit quicker if you’re in the middle of France,” admits Allan. “But when I got into the car… it had massive power, and a lot more downforce than I expected – it really did make me smile.”

Allan signed for Porsche in 1997, acting as a back-up driver for the Works team alongside a season in the US with Andy Pilgrim for Rohr Motorsport in a customer 911 GT1.

The difference in environment between the cut-throat world of single-seaters and endurance racing was stark. “I definitely didn’t want to share my toys – initially I would set the car up solely for me. While that was a good attitude for qualifying, it was crap for the race.”

Allan credits the likes of Stéphane Ortelli, Yannick Dalmas and Pilbeam for showing him the ropes, and the wider team. “Coming via the single-seater ladder you’re focused entirely on yourself, and for the teams you’re kind of a plug-in for the space that sits between the seat and the steering wheel,” Allan says.

“At Porsche I felt that I was part of a team; the 1997 season was a case of them understanding whether I could actually race and overtake people, and was as quick as I said I was. I also had to think about whether this was something I wanted to do.”

It was a challenging year for Porsche, with the car evolving as the season progressed, leading to the GT1 Evo package, as seen on no. 004. “It was all aero,” says Allan. “It had more downforce and was therefore more stable. The platform had to be a bit stiffer, too, so it was better for me – the feedback was much sharper, more aggressive, and I could feel the tyres better, so I wasn’t sliding over the top of them. I could feel the edge of the tyre, so I could run a softer compound – so for me it was a little bit here that gave a lot in the total picture.”

There were more developments under the skin. “We started to play around with sequential gearboxes, more in testing than racing,” Allan recalls. “The first GT1 had a big old H-pattern gearshift, and was a bit of a truck. We started racing the sequential gearbox at Daytona at the start of 1998 – it wasn’t very fast or particularly good.”

Although Allan would hop across the globe for the Works team in the FIA GT series at Zeltweg, Suzuka and with the Roock customer team at the Le Mans 24 Hours, his best results came alongside Andy Pilgrim for Rohr Motorsport in IMSA with three victories. IMSA was a culture shock for Allan.

“There’s one fundamental difference between racing in Europe and in the US: in America, the racing is for the people watching on television and in the grandstands, whereas in Europe it’s for the people in the paddock, in the teams,” he explains. “The regulations are built up in the same way. With full course yellows you can get your laps back if you fall behind – at my first race in Vegas in 1997, I thought ‘what the hell is this?’ I thought that if I drive the fastest, and so does my team-mate, we should win by X. But after being in America, I realised that wasn’t good for the team or the driver.”

McNish has come to regard his American drives as some of the best racing in his career. “They’re the ones I remember, where you pick out the trophy, or the pictures, or I’ll phone up Dindo Capello and reminisce about Petit Le Mans races,” Allan laughs. “What you’ve got to understand about racing in America is that you’re never out of the game until the chequered flag.”

That mantra also means a certain sharpening of the racing attitude. “You’ve got to be ruthless – the fans like a bit of rough and tumble. They love the fact that you will spin going out of the pitlane and kick up smoke everywhere, and they like the fact you come in and, you know, ‘have a discussion’,” Allan says. “In Europe, all of that’s frowned upon – that’s not to say that Europe’s bad, because the racing is very clean and clinical, and super high level – but there is a very big difference.”

Come the year’s end, Allan had come to a conclusion. “It was pretty bloody clear [sportscar racing was] what I wanted to do, and they thought I was worth the risk of throwing in the Works car for the FIA GT race at Laguna.” Damage to the Rohr 911 GT1 meant McNish got a chance in a Works 911 GT1, which meant a lack of practice time.

While he had visited Laguna Seca to see his good pal and fellow Scot Dario Franchitti race there in 1996, he hadn’t driven it in anger: “I remember asking Dario about the Corkscrew. He said: ‘When you go up the hill, everything’s fine – you turn in and when you see the tree, you go for it. That’s the point to go down the hill.’ I thought, fair enough! What he didn’t say was that there were five trees, all lined up – so which do you go for?”

Despite this (it was the middle one, incidentally), Allan took to the track well, despite it not aligning to what he terms his “skill-set”. “It was very low grip, and normally I’m not very good on such surfaces – despite being from Scotland,” he laughs. “However, it needed a lot of precision, and it required you to attack it to get tyre temperature – that worked for me, because I really attack corners. I throw cars into corners, and really hang it out – I wasn’t one to sit and wait on the front end. I would try to get the rear into the corner – and it worked for me.”

While Allan was quick all weekend, he did tweak the set-up slightly. “I wanted a little more stability down into the first corner – you’re coming downhill, and you’re starting to brake as you turn left,” he muses. “The car was a little bit soft and it moved around underneath me, so Norbert Singer and Brad Kettler knocked on a bit more wing.”

After that, it was all about tyre pressures and compounds. “I think we had three different tyre compounds on four corners of the car when it came to the race.”

Against the dominant Mercedes-Benz team, McNish and Kelleners lined up fourth on the grid behind the three CLK GTRs – not bad considering the Porsche GT1 had been largely off the FIA GT Championship pace all year. Things soon got much better, though. “I suppose I was quite good with rolling starts because of karting, but I also realised I had to get stuck in,” Allan says, although the conservative Benzes came as a surprise. “I thought they all braked far too early – I just ran around the outside of one Mercedes-Benz (Alessandro Nannini), and let it roll around the outside of the second one (Wurz) in the double left-hander. Then I nudged up the inside of Bernd Schneider, who made it a lot easier by sliding off the road a bit.”

From there, Allan was able to build a gap of around four seconds. “I was easily quick enough in all of the sections of the circuit, apart from the final corner, so they couldn’t get close to me,” he remembers. “We had the performance and speed to win the race.”

It wasn’t to be, however. After handing over to Ralf Kelleners at the end of his first stint, there was a problem with a wheelnut that dropped the car to third place, with the GT1’s low-speed pick-up hampering Ralf and Allan’s attempts to move further upfield. “Laguna’s not a circuit where you can overtake easily, and we weren’t the quickest out of slow corners because the turbo restrictor was right beside the turbo itself,” explains Allan. “That hampered us a lot coming out of the last corner, which meant [overtaking on the] run down to the first corner was impossible.”

Schneider would take the win and the driver’s title for Mercedes-Benz, while McNish would finish third. “It was bittersweet – we went out and drowned our sorrows, but it was also a bit of a celebration,” says Allan. “I was satisfied with my performance, I couldn’t have done more.”

It certainly made the Porsche hierarchy sit up and take notice. “It confirmed to them that it was worth taking the risk on a young kid who thought he was the fastest thing in the world,” Allan reflects. “Ultimately it led to 1998 and everything else – Laguna Seca was my first big knock on the door.”

The Heveningham Concours takes place on July 8-9, 2023 – more details are available here.