WORDS: PAUL CHUDECKI | PHOTOS: DAVID MONTGOMERY

Print article from Magneto issue 16

It marked a major moment in the motorcycle world; the arrival of the first British ‘superbike’ in two decades. Not only was it this that drew the attention of the global press, it was also that this exclusive, hand-built machine was to be produced by no less than a peer of the realm. Not just any old peer, either, but one already famous – indeed, infamous – for his successful activities in the top echelon of the four-wheeled world of motor sport.

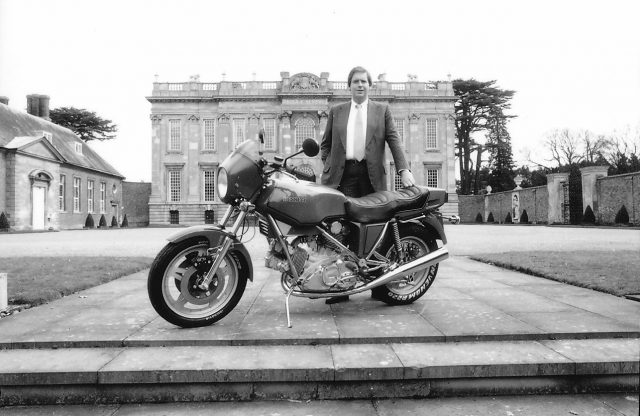

Lord Thomas Alexander Fermor- Hesketh had formed the agreeably non-conformist Hesketh Racing Formula 1 team in 1973, at Easton Neston House, the 1702 Nicholas Hawksmoor-designed stately home set amidst a 3300-acre estate near Towcester, Northants. Known for his extravagance, eccentricity and hospitality, the just 22-year-old 3rd Baronet Hesketh financed the team solely from his personal fortune.

F1’s naysayers wrote off Hesketh Racing as the plaything of a bunch of party-loving toffs, but that attitude swiftly changed when the in-house- designed Hesketh 308B-Cosworth beat Niki Lauda’s Ferrari 312T to 1975 Dutch Grand Prix victory. The team finished fourth in the World Championship, putting driver James Hunt on the road to F1 stardom.

Following Hesketh Racing’s 1976 withdrawal from F1, it continued with its well established engineering development and consultancy work for car and racing fraternities. It also ran a busy operation rebuilding many teams’ Cosworth DFV engines. To fill the F1 void, in late 1977 Alexander along with MD and business partner Anthony ‘Bubbles’ Horsley decided to create a new, entirely hand-built superbike, complete with an in-house engine and gearbox made by Weslake. It was just the sort of fillip the home motorcycle industry needed – a sentiment shared by Alexander.

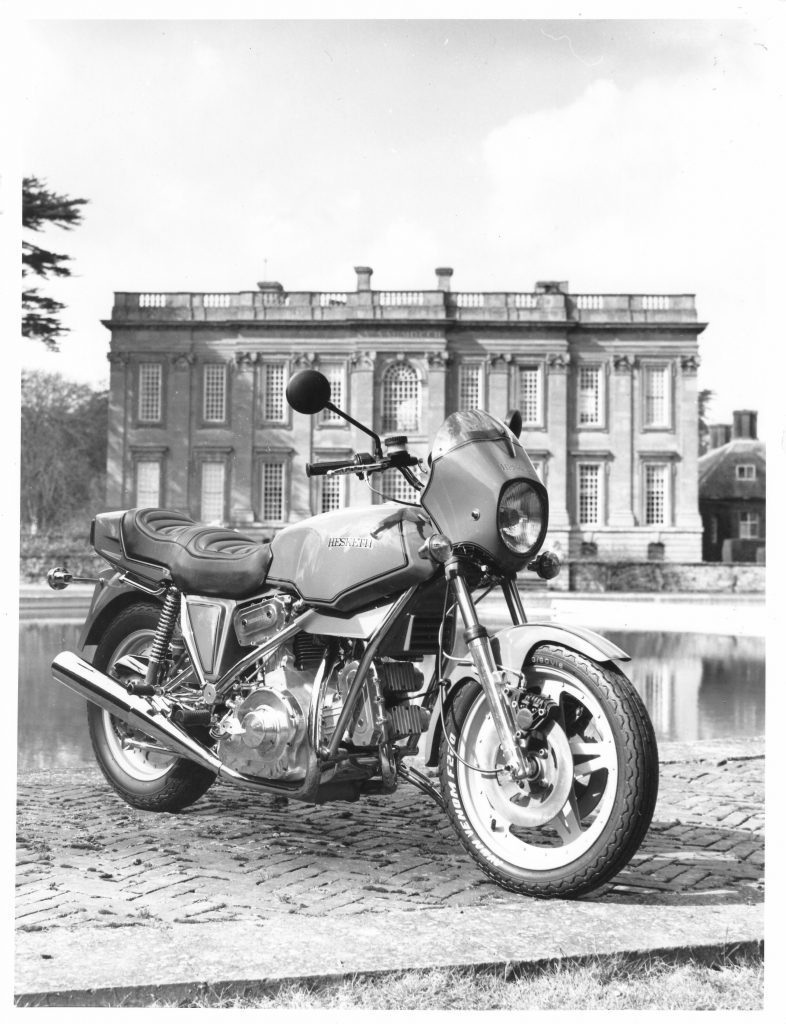

Yet this aristocratic, two-wheeled roadster-cum-tourer would not be designed by motorcycle engineers, but by Hesketh F1 luminaries such as Frank Dernie and Nigel Stroud, while its glassfibre bodywork would be styled by John Mockett. And it would boast several notable features, including a rigid, Reynolds 531, nickel-plated frame with entirely straight tubes, a semi-stressed engine eliminating the need for tubes in front and below it, and sophisticated rear suspension co- axial with the ’box output sprocket to maintain constant chain tension.

Of his decision to build a two- wheeler, Alexander – who has twice failed his motorcycle test – recalls from his Kensington home: “We sort of talked about it. I was never a biker, but Bubbs was; a lot of people at Hesketh Racing rode bikes. I’ve never really had much interest in motorcycles to be honest. They scare me.

“The closest we ever got to doing any market research was we bought a BMW, a Laverda, a Yamaha and a Ducati, to have a look at them. I don’t know why we wasted the time or money, because in principle we decided a traditional British bike must be a 90o , inline V-twin, in order to get as low vibration as you can.”

So it was no coincidence that Cosworth’s legendary F1 DFV V8 would provide key elements of the Hesketh’s quad-camshaft, eight- valve, all-alloy 992cc twin: “Basically, if you look at the cross-section of the engine it’s the end two cylinders of a DFV,” continues Alexander, who has a deep appreciation for excellent engineering as well as aesthetically appealing mechanical components.

“We went for that because we knew how much power we got out of the DFVs. The four-cam was there for marketing, because we had to have something that was exotic. We thought: ‘We know what a DFV does, we know that DFVs are reliable, so why don’t we dimension it exactly like a DFV?’ Because that’s what it is. It’s a V-twin DFV, to the extent that the prototype engines at Weslake had DFV pistons, because dimensionally it was identical. It also happens to do with the primary vibration problem, so all of that went in.”

Weslake’s contract had been to build, develop and deliver five pre- production engines and ’boxes, after which development continued at Easton Neston. The drivetrains were fitted into five prototype bikes; production machines would then be built at Hesketh’s Oldham factory.

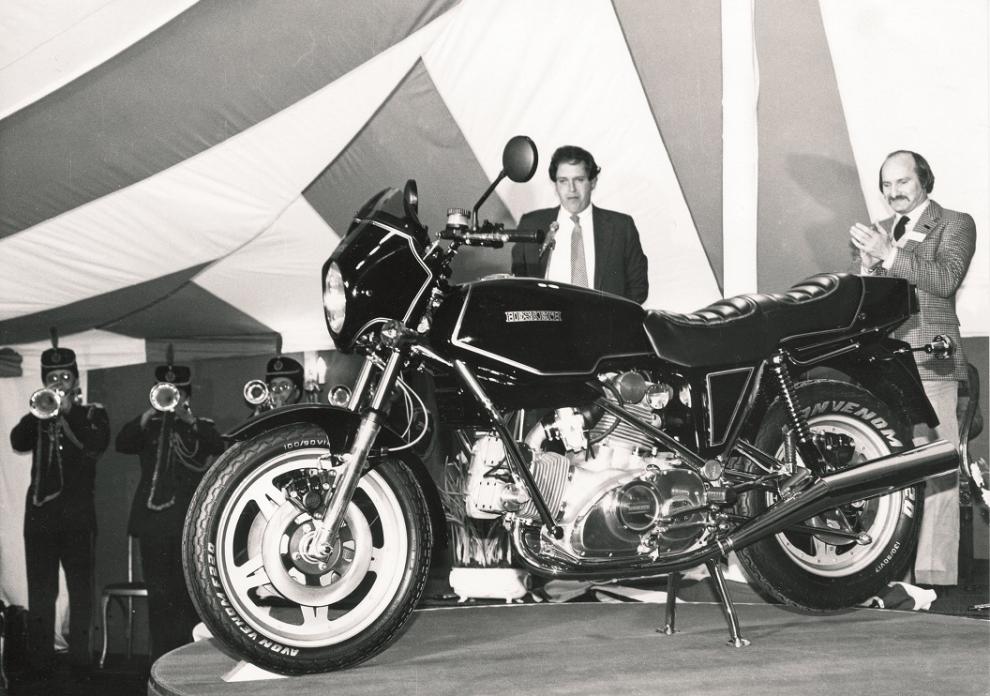

The resultant V1000 model’s April 1980 press launch was a naturally extravagant affair, with a brass band, glamorous women and great quantities of Champagne. It was all in keeping with both Alexander’s inimitable style and his exquisitely crafted and expensive motorcycle (£4500 – £1500 above BMW’s top RS100 model), and oh so British in character.

The strikingly handsome machine and its imposing V-twin drew gasps of approval. Its 90 percent British content was highlighted, including Astralite wheels (as seen on the F1 cars) with Avon rubber and Girling rear shocks. Only the Marzocchi forks, Brembo brakes, Dellorto carburettors and Nissan Denso instruments were sourced beyond home shores. Motorcycle legend Mike Hailwood demonstrated the bike on Easton Neston’s driveway.

But the V1000’s launch, at a time when the economy was on the back foot and Japanese bikes dominated, belied two major issues. The first was a lack of money to proceed, leading to a successful floatation in September.

“We didn’t have a choice,” Alexander explains. “I couldn’t afford to put it into production, so we had to raise money – and you can’t raise money unless the world is aware of it. The one thing that mucked us about was there was something wrong with the casting in the production bike; someone had tragically changed a drawing, and so there had to be a change on the cast. We had to raise another £400,000-£500,000.”

The second issue was impending engine and gearbox-selection troubles – specifically an overheating rear cylinder due to excessive crankcase pressure that reduced top-end lubrication, and also a design flaw that baulked first-gear engagement.

Shortly after February 1982’s first customer deliveries, these issues were overcome by the EN10 engine conversion, retrospectively fitted to the initial batch. Nonetheless, this did not help the V1000’s reputation, already tainted by early road tests the previous August that varied from praiseworthy to derogatory.

All riders, however, were impressed by the bike’s stable, nimble handling, which belied its hefty 500lb (227kg) weight, and the power and torque – 86bhp at 5000rpm and 72lb ft at 6750rpm – of its lusty, beautifully presented engine. Each unit was blueprinted to Cosworth spec, and the combination was akin to the punch and agility of a heavyweight pugilist, while the five-speed gearbox received a major revamp.

By August, however, when just 139 bikes had been produced, in the midst of a recession and with superbike sales falling through the floor, Hesketh Motorcycles Limited entered receivership. It simply lacked further finance. Following an auction of £250,000 of stock, including five unassembled bikes, the company reformed in December as Hesleydon Limited.

Back in 1978, highly experienced engineer and racer Mick Broom had been the first motorcyclist to join the engineering team – a mere two or three in those early days, based in Easton Neston’s stable-yard laundry, the unlikely former F1 team setting for the beating heart of development and testing of an exquisitely crafted motorcycle; later, operations would overflow into the indoor tennis court.

After Hesketh’s floatation, the team – with Mick heading engine development and serving as one of three test riders – grew to seven or eight people. The man who has since done more to keep Heskeths on the road than any other, remembers that auction well.

He recalls: “Bubbles had a word with me, and said: ‘Look, if we do anything more, do we need anything from the factory?’ I said: ‘Well, the only thing that you wouldn’t be able to get round is the gearbox jig,’ so that’s the only thing I bid on. But then, these guys who had bought stuff, I’d go and buy it back off them, and so we got forks for a few quid. They had got all the gearboxes, probably for two quid a time; I gave them £50, and we got the residue back. I finished up going round the North Yorkshire Moors pulling gearboxes out of chicken sheds.”

Alas, exacerbated by the market downturn and increased production costs, a severe lack of finance intervened again in September 1983; many staff redundancies ensued. By January, Hesleydon – which had sold some further 50 bikes, mostly the well received, £6500 Vampire, launched in February with Mockett’s stylish and effective full fairing – was reduced to fewer than a caretaker handful. These included Mick and engineer/test rider Pat Devlin. In 1984-85, Mick would take over the operation as Broom Development Engineering.

As Bubbles reflects: “We were able to use a lot of what had been bought from the receiver for what was a bargain price, so we were able to make a reasonable profit out of each bike. This gave us the money to have stores, basically support the owners and sell a few more bikes. It was a plucky effort.”

Indeed, both Bubbles and Alexander remain good humoured about the experience. The ‘Good Lord’, as Hunt called him, remembers 1980’s flotation on the unlisted security market, having already invested his own £400,000.

“That’s very important, because there were four companies floated; one of the others became O2,” he says, bursting into laughter. “There were only four companies that went onto it, and it became the AIM market. We disappeared into a scrapyard somewhere outside Milton Keynes.”

And as for Hesleydon finally making some money: “Well, we may have done, but it all got ploughed back in. I’ve never seen a penny,” he roars.

Mick Broom’s company, however, continued with limited production, steadily selling bikes to the most far-reaching worldwide destinations, with prices starting at £12,000. In 1985, the firm built the one-off, V1000-based Vortan, a stripped- down single-seat ‘streetfighter’.

And in 2012 – having moved from Easton Neston to Turweston in Bucks in 2005, when financial issues forced Alexander to sell his family home of 400 years – it announced a new, £20,000 V1200 Vulcan, with re- engineered brakes, suspension, engine management and wire-spoke wheels.

“I came to an arrangement with ‘V1000’s press launch was an extravagant affair, with great quantities of Champagne’ Alexander,” explains Mick. “I’d got enough bits, pieces and knowledge to do a batch of six. He wasn’t interested in getting involved, for understandable reasons.”

Cruelly, a major burglary deprived Mick of £40,000-worth of spares, kit and bikes, crushing his Vulcan production plans: “As a one-off sort of businessman, that killed the idea.”

Thereafter he retired – he would later complete the sole Vulcan for a customer – and sold his operation to Paul Sleeman. Having formed a new Hesketh Motorcycles Limited, in 2014 Sleeman launched the N24 (Hunt’s race number) with a 2000cc American S&S twin, followed four years later by a supercharged 2100cc Valiant and, last September, a 450cc Honda-engined model.

One of the V1000’s major points of appeal, of course, was its in-house engine. “That’s why it’ll last; that’s why it gets in the books,” says Alexander. “But the reality was that you’ve got to make the engine to get in the classification. Look at Vincent; it didn’t make many bikes, but people look at them like Cartier watches. They are seen as works of art.”

In stark contrast to those heady Easton Neston days, the once- maverick bon viveur who shook up F1’s establishment later became a Government minister, House of Lords chief whip, leading Conservative peer, UKIP fundraiser and keen Brexiteer. Today, he retains many business interests; he’s been Hesketh Owners Club president since its 1982 inception.

And of what might have been? “To be perfectly honest, the only thing I got wrong – I mean, we got everything wrong, but everything right – the biggest mistake I think, we looked at two versions of the engine. One was using Weslake to do an air-cooled V-twin, and the other was to get Brian Hart to do a water-cooled V-twin.

“With the benefit of hindsight, I think the bike would still be in production if it had been water cooled, for a very bizarre reason. You could have put a turbocharger on it and gone berserk. Because of that, rather like Harley-Davidson, it would have got a following that would have ensured its survival.”

Now that really would have been something else.

Print article from Magneto issue 16

Thanks to Lord Alexander Hesketh, Bubbles Horsley, Mick Broom, David Sharp and the Hesketh Owners Club.