WORDS: WINSTON GOODFELLOW | PHOTOS: AUTHOR

‘Bespoke’, ‘one-off’ and ‘exclusive’ are terms often bandied about these days when speaking of ultra-expensive and limited-production models. If such manufacturers and their clients believe cars with double- and triple-digit production numbers are truly ‘exclusive’ and ‘bespoke’, they need to examine a 5000GT to properly understand the words’ meanings. That magnificent Maserati was likely the world’s fastest car in the late 1950s and early ’60s, and it still makes quite an impression when driven today. Most importantly, its story has numerous elements that the ‘moderns’ simply can’t touch.

That list starts with DNA rooted in World Championship endurance racing, an arena in which Maserati had competed since 1947. Starting with the Tipo A6GCS, each successive model gained more power and speed, and by the mid-1950s Maserati was locked in an epic battle for sports-racing supremacy with Ferrari, Jaguar, Aston Martin and others. Its 300S was a beautifully balanced car that visited the winners’ circle, but with Ferrari unveiling new and ever-more powerful V12s in the mid-1950s, Maserati realised its reliable inline six- cylinder couldn’t compete, no matter how well rounded the 300S was.

This article first appeared in Magneto issue 4.

Which is how a second element enters the 5000 story. Tony Parravano had quite a reputation in Southern California’s real-estate construction industry, and he would make an even bigger splash in 1960 by vanishing while owing a very large IRS tax bill. In the mid-’50s he was Maserati’s biggest client, and likely acquired more fast racing machinery than anyone anywhere; as authors Michel Bollée and Willem Oosthoek note in Maserati 450S – The Fastest Sports Racing Car of the 1950s, by 1957 Parravano owned 17 competition cars valued at $500,000 – a hefty sum at the time.

5000 is truly a ‘mailed fist in a velvet glove’ – only this fist is Mike Tyson’s in his prime

During one of his visits to Modena, Parravano learned of Maserati’s still-born Tipo 54 4.5-litre V8, and that’s where the third (and a main) element of 5000GT history enters the picture. Giulio Alfieri was Maserati’s chief engineer and barely 30 years old. Brilliant, dedicated, very focused and driven, he perhaps more than any other individual formulated Maserati’s post-war automotive DNA. He and company president Omer Orsi recognised that the Tipo 54 project had the potential to best Ferrari’s V12s, and Parravano was a perfect means to making it happen. The construction magnate bit on their proposition, and with money now in the picture the 4477cc DOHC V8 powerplant was assembled and underwent development testing.

The engine was a honey. “Output was measured at 412bhp at 7000rpm,” long-time Maserati employee Ermanno Cozza noted in his delightful book Maserati at Heart. “(It) would accelerate up to maximum revs incredibly quickly without the slightest hesitation.”

Alfieri and his men then made a new chassis, and in-house coachbuilder Medardo Fantuzzi created a muscular, sleek-looking aluminium body. In October 1956 the first ‘production’ 450S went to Parravano in California, and the following year the model invaded racetracks in Europe and South America. It was far and away the fastest car in FIA endurance racing, typically running away from the field. Unfortunately that speed did not equate to luck, so while the 450S won two races, it was a DNF elsewhere. The real sting came in the season’s last event at Caracas, when the three 450Ss competing were all involved in freak accidents, causing Maserati to lose the championship to Ferrari.

In 1958, the FIA limited engine capacity to 3.0 litres, making the 450S obsolete on the Continent. Maserati didn’t have the finances to make something new, because its industrialist owner Adolfo Orsi (Omer’s father) took a tremendous financial hit when Argentina’s president Juan Perón was deposed. In April, 1958 Adolfo had to declare bankruptcy.

By now, Maserati had formally (but not completely) withdrawn from racing, but all was not lost. “At this time,” former Maserati employee Aurelio Bertocchi told me many years ago, “we had just started the (3500)GT programme. We decided to concentrate all our energy (in that area), rather than racing.”

A smart move that, for the 230bhp, 130mph-plus 3500GT remained the Modena area’s best-selling model for the better part of two decades. As the corporate turnaround took place and car sales grew exponentially, Giulio Alfieri said Omer Orsi sent a letter to the Shah of Iran, and included brochures of the 3500GT and 450S in the correspondence.

That’s how royalty – the fourth and likely most important element in the creation of the 5000GT – entered the picture. Then in his late 30s, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi had been king of Iran for nearly 20 years, and was a noted auto enthusiast. At 1957’s Paris Auto Show he purchased a Ferrari 410SA, and how quickly he responded to Orsi’s query surprised the two Maserati men: “My family had received a number of calls from the Iranian embassy in Rome,” Alfieri told me. “It was around 9pm on Saturday when my wife handed me the phone, saying they wanted to speak with me.”

During that call a meeting was set for the following day at the naval academy in Livorno, and Alfieri and Omer Orsi drove out to the coastal city. The Shah and his entourage met them at the academy, and after brief pleasantries the Shah “pulled out a sales sheet on the 450S”, according to Alfieri. “He said: ‘I want a car, using this as the basis. I’d like to have something special I can use on the street.’”

Just like that, Maserati had found another ‘Parravano’, someone who could bankroll a new project. The Shah, Orsi and Alfieri now identified the car’s parameters: a special, sporting two- place coupé with the powerful 4.5-litre V8 and a usable trunk. Alfieri then told the Shah he’d guarantee the model would touch 280kph, or 174mph. In the late 1950s, that would make it the world’s fastest production car.

With the concept determined Alfieri returned to Modena, where he had his men modify and reinforce the 3500GT’s chassis to handle the bigger, considerably more powerful V8. Suspension up front would be coil springs, telescopic shocks and an anti-roll bar. In back it was much the same, but with semi-elliptic leaf springs. Brakes were discs up front, and large drums at the rear.

Intriguingly, Omer Orsi’s personal diary showed his first choice for the 5000’s coachwork was Carrozzeria Bertone. The two companies had never worked together, but Orsi was likely captivated by Bertone’s avant-garde designs on Alfa’s BATs, Sportiva and prototype Sprint Speciale. Here, he wanted a more sober design. “This car must be viewed as a serious proposition for a real gentleman,” he noted in a December 9, 1958 letter to Bertone. “So do not incorporate too much fantasy.”

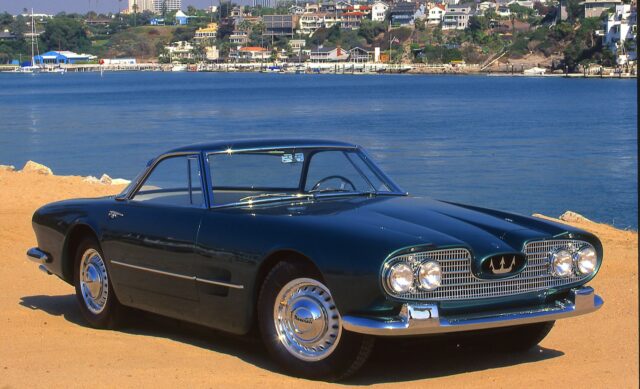

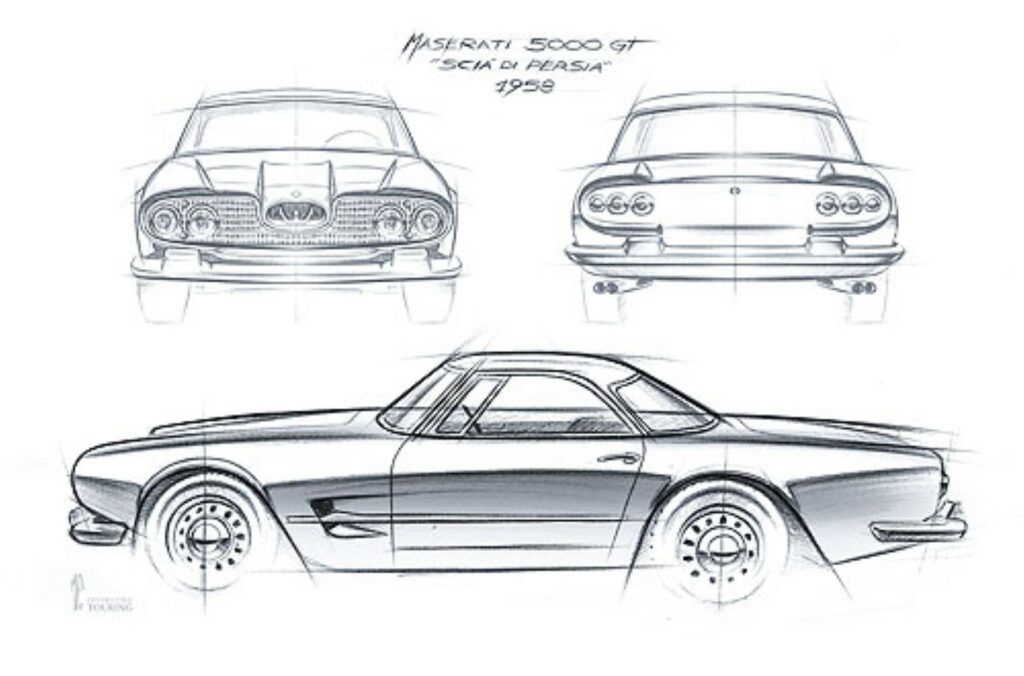

Bertone responded with a sketch that was included in Orsi’s December 20 letter to the Shah. His Imperial Highness wasn’t impressed, though, for in January 1959 Orsi reached out to Carrozzeria Touring. The stalwart styling house had been at the forefront of Italian design for three decades, with many of Alfa’s most famous pre-war models in its portfolio. When company co-founder and chief stylist Felice Bianchi Anderloni unexpectedly passed away in 1948, his son Carlo ably took over the design reins. His very first work was Ferrari’s seminal 166MM Barchetta, and other notables followed, including Alfa’s Villa d’Este and Disco Volantes, the Pegaso Thrill and the production Maserati 3500GT.

After being briefed by Orsi on the 5000GT’s parameters, Anderloni assembled his design crew and went to work. “With the 3500,” he told me, “that car was supposed to be understated – something that said you were important but not a star. The ‘Shah of Persia’, as the model came to be known, was a different school of thought. Here we wanted something imposing… to show the person inside was of wealth and importance.”

The coachwork Touring created had some design dichotomies. For instance, the side profile and proportions were clean and eye catching, while the front grille, oversized trident and headlight treatment were quite gaudy. But Carlo Anderloni was both perceptive and well travelled, so there was a method to the madness. “In retrospect,” he noted, “the style was baroque and heavy. As we liked our designs to reflect the culture of the customer, when we referenced examples of Persian architecture, it was often ornate and heavily embellished. While the front was a bit difficult for us, it clearly announced ‘an outstanding car is arriving’.”

By mid-February 1959, Touring’s sketches were completed. After their review at Maserati, they were forwarded to the Shah. Two weeks later a telegram arrived in Modena, His Imperial Highness very much liking what he saw and complimenting the coachbuilder’s efforts. Now the hard work began – engineering, building and testing the actual car.

“When you look at the problems the Shah was having with his 410,” Alfieri recalled, “the clutch gave him trouble, as did the ignition system (since) its power was correlated directly to the number of rpm. With a big engine like this, the electrical output could be a problem, especially if you are running at low rpm in top gear… This was a shortcoming with all of the era’s GT cars, and Italy’s industry in particular didn’t have the availability of some subsidiary elements to develop these components. So proper electrical systems and big clutches weren’t available.”

Maserati and other GT constructors thus turned to component suppliers in England and Germany. For the first 20-plus 5000GTs, ZF provided a four-speed transmission. Other external items included a Borg & Beck clutch, Girling shocks and front suspension components, plus a Salisbury rear end.

The Shah was kept abreast of his car’s build, and by early June he gave Maserati his colour choices. After a number of labour strikes delayed the model’s completion, in early September ace test driver Guerino Bertocchi was tearing up the autostrada; in testing, Alfieri recalled the 5000GT’s top speed slightly exceeded his 280kph ‘guarantee’. One month later, 5000GT chassis number 103.002 was at the coastal city of Genoa, and shipped to Tehran.

For Maserati, the Shah had indeed helped to underwrite a new product, so before his car was shipped a second Touring-bodied 5000GT was in the pipeline. “We constructed these type of cars with an artisan mentality,” Alfieri pointed out. “In a few short months we could go from the beginning to the end of a project. The cost to us was very small, almost nothing… because it was in the interest of the coachbuilder to do a joint venture with us.”

The second 5000 (chassis 004) debuted at 1959’s Turin Auto Show carrying a $12,500 price that was quite a bit higher than the 3500GT’s sticker. It was worth every penny, based upon what Hans Tanner wrote for the February 1960 issue of America’s Sports Car Graphic. He rode shotgun as Bertocchi put it through its paces, all while timing a kilometre run at 172mph.

“If anything can be said about this fabulous car,” Tanner concluded, “it is only that these speeds are too easy. At 170mph the car seems to be doing 90mph, and I feel without a skilful driver at the wheel the effect could be disastrous.” It was a most prescient observation, considering the number of today’s corresponding supercars that end up wrecked in photos and videos online.

Following the Turin show introduction, it took a while for the word on Maserati’s newest and most exclusive car to get out, as only two 5000GTs were made in 1960 (a third Touring ‘Shah of Persia’, and the first of two by Monterosa, a small coachbuilding firm headed by ex-Bertone shop foreman Giorgio Sargiotto). Nine 5000GTs were produced in 1961, and with that spike in volume Italy and the automotive world had its ultimate canvas for creating true custom coachwork. That year the big-name carrozzerias and some smaller ones made bodies (Pininfarina, Ghia, Bertone, Allemano, Monterosa with its second car, and Michelotti), while many of the top stylists (the aforementioned Giovanni Michelotti, Giorgetto Giugiaro, Sergio Santorelli, Filippo Sapino and more) designed the coachwork.

A greater number of 5000GTs were made in 1962 (14), with production settling down between Carrozzeria Frua (two that year), and Allemano. In fact, it was the latter that bodied the most 5000GTs, with 22 in total – the unique Indianapolis that was shown at Turin in 1961, and 21 ‘production’ versions that weren’t quite as sleek but still eye catching.

Mechanically, the 5000GT was refined and updated throughout production. The first two cars had an enlarged version of the 450S’s V8, where a larger bore bumped capacity to 4935cc. The compression ratio was dropped to make the powerplant more suitable for road use, and the 340bhp engine was topped with four dual-throat Weber carburettors. All subsequent 5000GTs had a fuel-injected 325bhp 4941cc V8, and a good number were fitted with Girling discs front and rear. A ZF five-speed trans became standard in June 1962 on the 23rd 5000GT built, chassis 044.

In total, 34 5000GTs were produced from 1959 through 1965, and the list of commissioning clients was a literal who’s who of global commerce, show business, politics and more. First owners included business magnates Ferdinando Innocenti and Gianni Agnelli, US sportsman Briggs Cunningham, film and stage actor Stewart Granger, an Italian count, an Italian prince, King Saud of Saudi Arabia, a Saudi prince, the president of Mexico, and Prince Karim Aga Khan, the spiritual head of the Ismaili community.

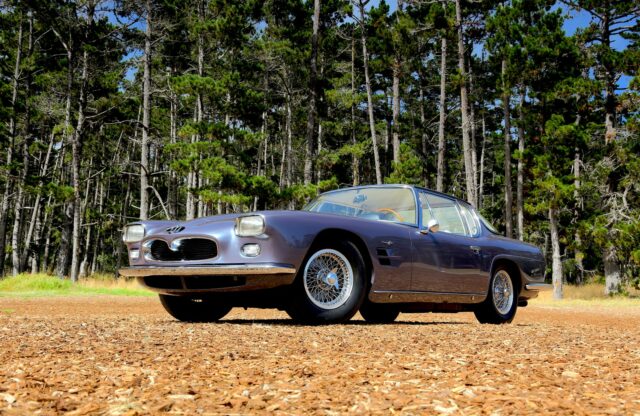

Featured here is the Aga Khan’s 5000GT, chassis 103.060. Its intriguing and influential coachwork came from the fertile mind of 49-year-old Pietro Frua, who founded his carrozzeria in 1946 after stints at Stabilimenti Farina as a designer and manager, and Carrozzeria Viberti. Frua specialised in custom coachwork and small production runs, and in the 1950s had designed and created bodies for 26 Maseratis on the A6/2000 and 3500GT chassis. His 5000GT’s design became the basis for Maserati’s Quattroporte that debuted in 1963, and also heavily influenced the Mistral berlinetta.

Frua’s first 5000GT broke cover at the Geneva Auto Show in March 1962. Maserati’s French importer John Simone bought chassis 048, and according to Maurice Khawam in Maserati 5000GT: A Significant Automobile, the Aga Khan also used it, and was quite fond of it. This led the Aga Khan to commission his own car, which returns us to the true meaning of terms such as ‘bespoke’ and ‘exclusive’. Chassis 060 is the second of just three Frua 5000s, and while they are all similar in appearance each was indeed unique. This 5000 is the most custom of the trio, ordered with lovely light metallic blue penombra (‘twilight’) paint, and a record player installed in the dash.

Why someone would have a giradischi in a machine with a powerplant as musical and charismatic as this is a good question, for on the road a properly running 5000GT is one very impressive gran turismo. Open the large, hand-formed door and slip into a comfortable seat, and behind the artful three-spoke wooden wheel is a fabulous dash dominated by a large central tachometer. The car’s superb greenhouse gives you an expansive view all around, especially over its sculptured nose.

Fire up the Maser, listen to it burble at idle and feel its subtle shimmy and minute vibrations; as it talks to you while sitting still, it exudes something most of today’s ultra-fast cars lack – a truly distinctive character and aura that are unlike anything else. A slightly grabby clutch is the only real shortcoming, and you master this by using the Porsche Carrera GT technique of minor throttle input with a fluid clutch-release motion.

In low rpm at slow speeds you can feel the burliness of the V8’s brute power and competition breeding, and how it just wants to go. It’s like a racehorse constantly tugging at the reins; I soon succumb to its urging, and floor the throttle. Take-up is instant, linear and unrelenting, its powerful musical roar like a thousand handmade, perfectly pitched and tightly compacted aluminium canisters shaken in unison. It’s simultaneously melodic, mechanical and brutal, and it magnificently increases in amplitude as the large needle quickly sails around the tach.

This engine has barely 200 miles on a complete rebuild, and because of that I pay close attention by shifting a bit short of the indicated 5000rpm red line. This is necessary, for this mighty V8 revs so freely it feels like it will rip right past the red line and easily romp up to the comp motor’s 7000rpm power peak. That DOHC fuel-injected engine’s symphony and its smooth but fierce acceleration are utterly addictive, and several times I slow to a crawl, mash the throttle and run the Maser through the gears. The five-speed ’box is a bit notchy and tight, which makes for precise throws. The suspension is quite compliant, and possesses that elusive pillowy ride found in the best of the upper-crust 1960s’ GTs.

At almost every speed there is a magic-carpet feel that cossets (but does not isolate) the driver and passengers from the road, and absorbs bumps beautifully – which includes when you are forced to slowly potter behind tourists on Pebble Beach’s famed 17-Mile Drive. Add how the car surrounds you with hand-built, luxurious craftsmanship, and Ferrari’s 410SA feels crude in comparison; the 400SA even a little milquetoast.

In sum, this 5000 is truly a ‘mailed fist in a velvet glove’ – only this fist is Mike Tyson’s in his prime. If I’ve harboured any doubt about the car’s ability to seriously captivate and beguile (which I don’t), my friend Shane Mustoe soon dispels any such misgivings. A fast and smooth driver, when Shane gets out of the Maser after a brief stint at the wheel he is literally beaming and talking a mile a minute.

Making his ebullience particularly noteworthy, and speaking volumes about the car’s unique, enthralling character, is that he is much more of a Lotus Elan type than a 5000GT driver… Special thanks goes to Adolfo Orsi for help in researching the 5000GTs and their history, and his guidance in all things Maserati.

Magneto drives Maserati’s Ghibli 334 and Levante Ultima – the marque’s V8 swansong – here.