WORDS: ELLIOTT HUGHES | PHOTOGRAPHY: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The aftermath of a global pandemic, conflict, recession and high taxes. If it’s any consolation, 2022 isn’t the first time humanity has faced such a cocktail of misfortune; something similar occurred precisely 100 years ago. The silver lining? The creation of one of the most influential cars in motoring history: the Austin Seven.

Moving on from the poetic if somewhat perverse repeat of this seemingly unlikely amalgam of woe, it will certainly be fascinating to see whether the baton is passed to another car that revolutionises human mobility to the extent that the Seven did, particularly when the future of motoring seems just as murky as it did back then.

So, to find the answer, let’s journey back to 1922 to discover how the little Austin managed such a feat, and celebrate its contributions in shaping the rich automotive culture of today.

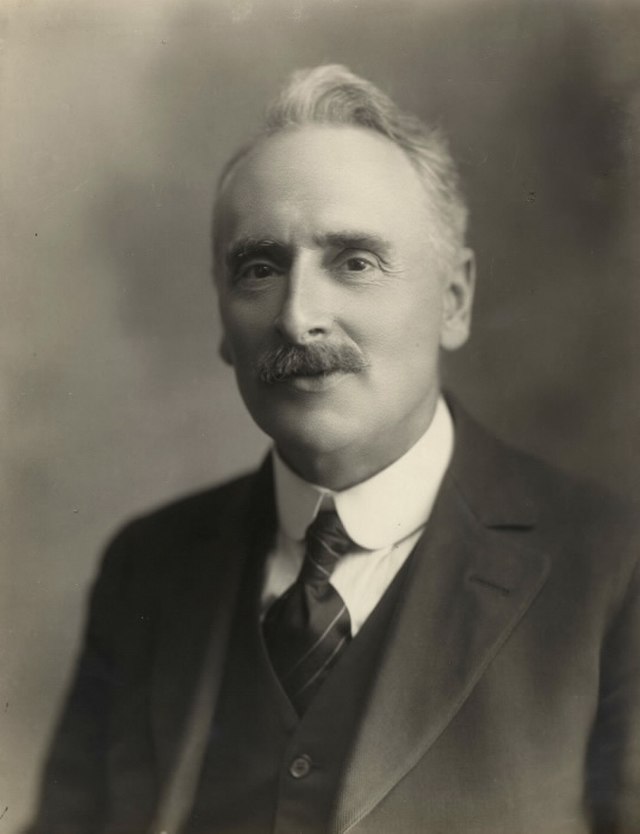

In 1922, marque founder Sir Herbert Austin had a problem. Britain’s post-1918 boom had come to an abrupt end, and as a consequence, car sales had contracted by an alarming 50 percent. Helpfully, the RAC also decided to increase vehicle excise duty to £1 (£40 today) for every horsepower produced – working on a strange classification system determined by engine format rather than measured brake horsepower.

Predictably, Austin’s catalogue of large, expensive and relatively powerful cars was not conducive to strong sales in such an economic climate, and everyday Britons turned to loathsome cycle-cars and motorcycle-and-sidecar arrangements to fulfil their logistical needs.

Sir Herbert’s back was against the wall. His once-successful company was on the brink of bankruptcy and languishing in receivership. Something had to be done. It’s at this point that he identified a gap in the market for a small, utilitarian machine that could affordably solve a family’s transportation needs.

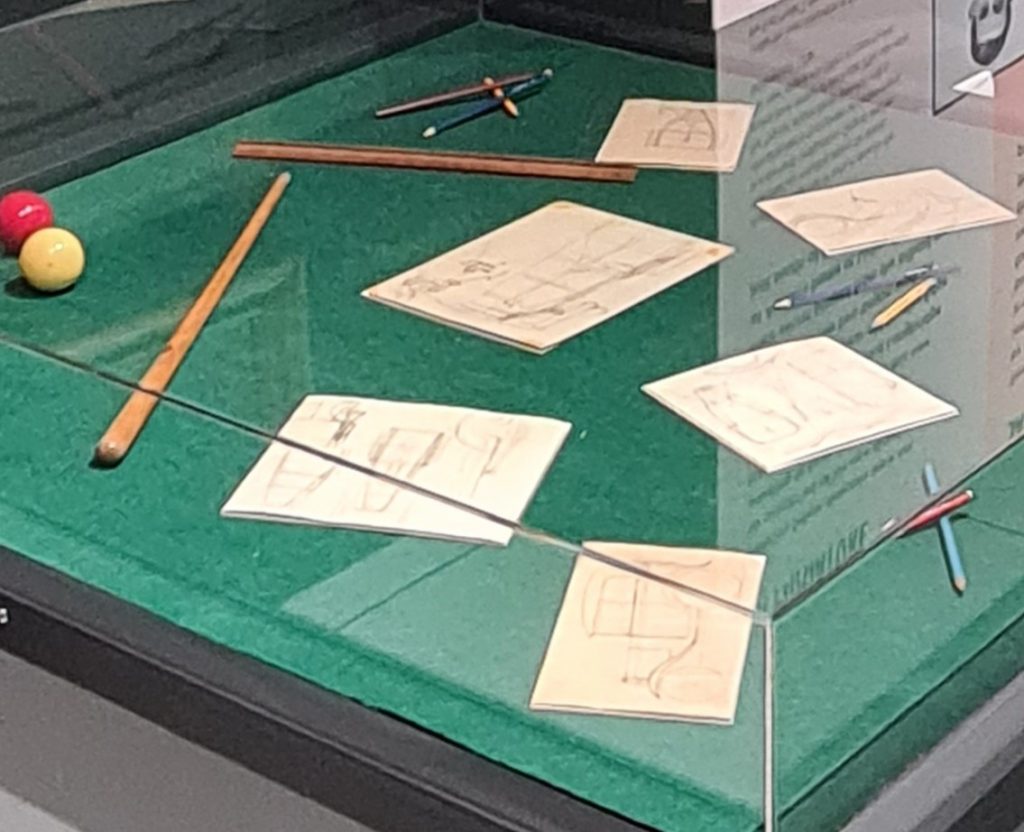

The success of the Ford Model T in the US demonstrated the precedent for such a car, but the Seven was met with vehement opposition from Austin’s backers, who rejected the idea. Undeterred, Sir Herbert enlisted the help of a talented 18-year-old draughtsman named Stanley Edge from Austin’s Longbridge factory, and set to work in his billiards room at home.

Those billiard-room blueprints would lead to something extraordinary. Artfully simplistic, the design was underpinned by a basic chassis with two main beams running the length of the car, leaf-spring suspension, four-wheel drum brakes, four seats and a three-speed manual transmission controlled by today’s ubiquitous clutch, brake, accelerator pedal layout that was by no means conventional at the time.

Initially, a miniscule 696cc four-cylinder side-valve engine resided under the bonnet, but it was enlarged to 747cc shortly afterwards for a power output of 9.8bhp. That meant that the bravest drivers could take the tiny 350kg Seven to 47mph (which is a terrifying prospect, as anyone who has driven one will tell you).

Priced at just £225 (£8930 today) at launch, the Seven mirrored the cost of a motorcycle and sidecar – and the public response was enthusiastic to say the least. Austin sold 2500 Sevens in the first 12 months, and by 1926 so many had been bought that the price dropped to just £145 (£6200).

The Seven’s popularity continued, and 100,000 had been sold by 1929 with the model capturing a remarkable 37 percent of the British car market, sentencing sidecars and cycle-cars to obsolescence. Longbridge had produced 300,000 examples by the time production wound up in 1939, and around 7000 are believed to be extant today.

Yet accessibility is not the sole reason for the Seven’s lasting greatness, nor is its precocious control layout and simplicity. It’s the combination of these attributes with the car’s sheer versatility that meant its influence is still being felt 100 years later; Sevens permeated all walks of life and were used by the military, delivery drivers and tradesmen.

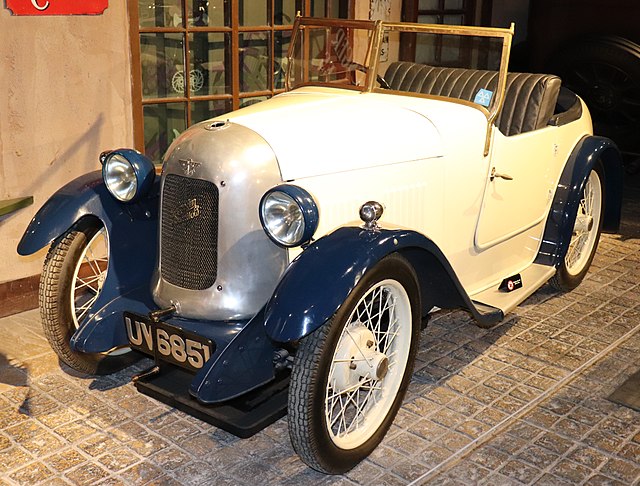

The Seven’s versatility was partially down to its conventional body-on-chassis design that allowed coachbuilders to create their own bodies for the car. These qualities attracted the attention of various manufacturers that are now among the world’s largest and most significant marques.

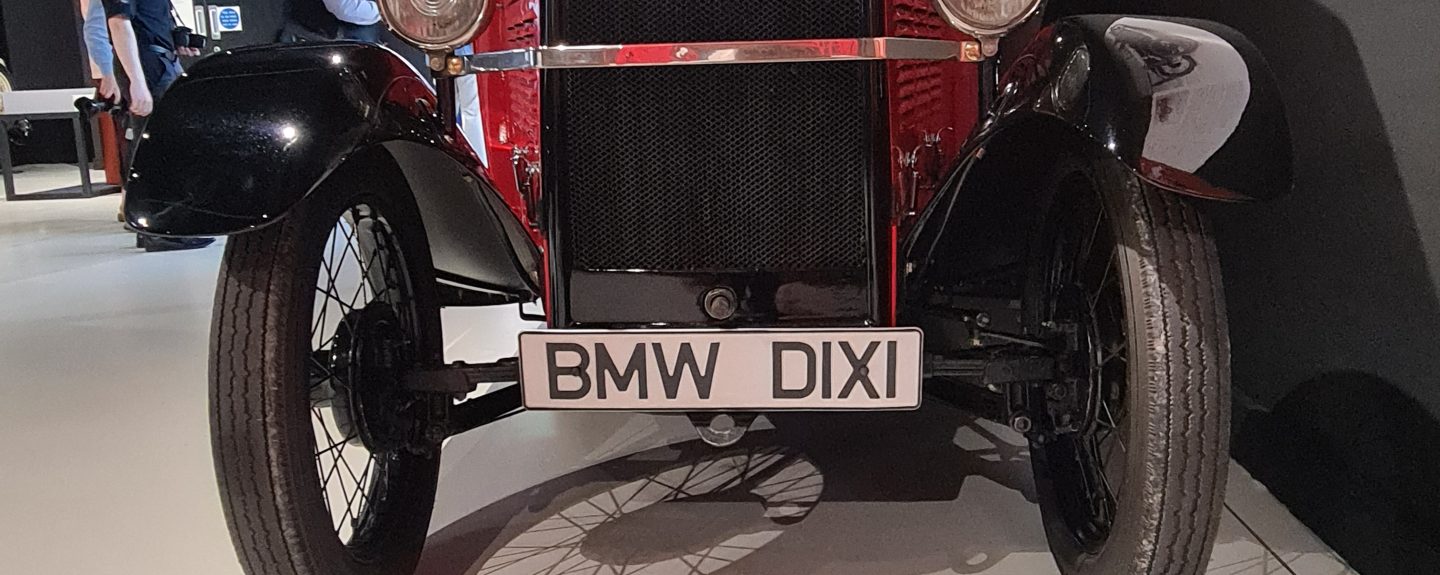

One of Nissan’s earliest cars, for example, was the Datsun Type 11, which was an Austin Seven built under licence, and over in Germany the car was built under BMW as the Dixi. If that wasn’t enough, the Seven also made cameos at the dawn of Holden, Jeep and Jaguar.

Perhaps the Seven’s unlikeliest legacy is the role it had in fostering Britain’s standing as a pioneering motor sport nation. In period, the car became the first 750cc machine to achieve 100mph on the hallowed banking of Brooklands. It even competed at the Le Mans 24 Hours. Meanwhile, private owners used their Sevens for circuit racing, hillclimbs, rallies and trials events – a tradition that continues today.

Soon enough, now-venerated pioneers such as Colin Chapman and Bruce McLaren began experimenting with the Seven by chopping down its rudimentary chassis and modifying its powertrain and suspension components to create racing specials.

Although Seven production ceased in 1939, its philosophy of compact, affordable and cleverly packaged transportation lived on when Alec Issigonis created the Austin Seven Mini in 1959 – better known as the classic Mini.

Maybe the challenges confronting today’s world will give rise to a 21st century equivalent of the Seven; a panacea to the economic and environmental hurdles that face today’s car builders. If history is cyclical then the baton won’t be passed to an expensive EV from the likes of Tesla or Lucid; it will be a humble, unassuming car built from necessity, whose impact will be celebrated in 2122.