WORDS: JONATHON BURFORD | PHOTOGRAPHY: SOTHEBY’S

I’m very aware that in the modern world a mechanical watch, especially a vintage one, can be perceived as an obsolete and often expensive indulgence by those who don’t understand the passion many of us feel for these mechanical marvels. Our attachment is often based in romance, in our belief that watches tell us stories about these incredible watchmakers and the times they were working in, and the people who owned them. This helps to explain the desirability of watches with military-, diver- or explorer-related provenance.

Another way we connect these stories is through the first retailer. Who was buying these beautiful, complicated Patek Philippes from Venezuela’s Serpico y Laino or Uruguay’s Freccero? Before wide international travel and brand boutiques in every city, these small retailers were the gatekeepers, selling the most important watches to the most interesting collectors.

Take Gondolo & Labouriau. In the early 1900s, Brazil’s gambling ban led to the creation of the private-members’ Gondolo Club. Each member was required to buy a Patek Philippe for 790CHF, and they also received a unique number via raffle. Each member then paid 10CHF per week until their watch was paid for; however, Gondolo & Labouriau would host a weekly draw in which the initial winner received his watch for free, the second week’s winner had to pay a minimal amount and so on. By the 79th week, the remaining members had to pay the full amount for their watch – an ingenious circumvent of the gambling laws.

For years the brands’ retailer was their only access to these clients located all over the world, and the retailer/client relationship was as strong as that between brand and client. Primarily, these retailers would add their names to only the most important watches they sold, such as complicated Pateks or Audemars. However, there are also some unexpected and rare retailer- stamped watches such as Hermes’ unique gold Rolex Daytona with Paul Newman dial, and another by Van Cleef & Arpels, or seldom-seen examples of sports Rolexes with Cartier-stamped dials retailed from the brand’s Fifth Avenue flagship for a short period in the 1960s.

London’s Asprey not only added its name to the dials, but struck a unique agreement with Rolex and other brands where it added the Sultan of Oman’s Khanjar to the dial, sometimes even replacing the Rolex text below the coronet.

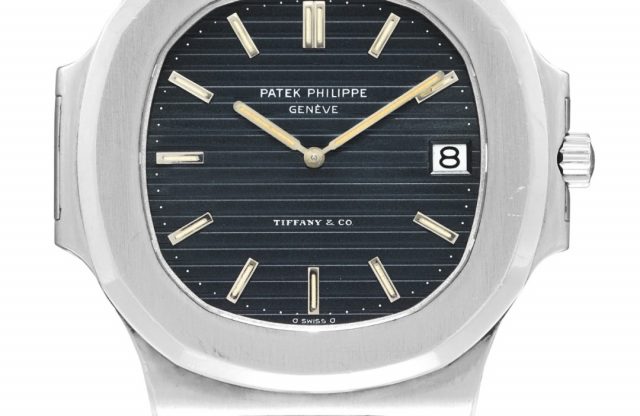

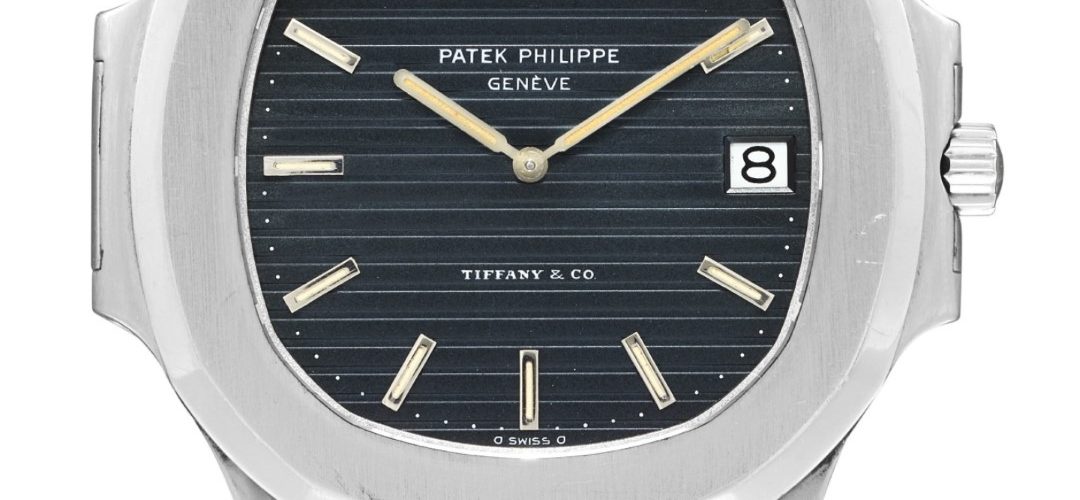

Probably the most famous and continuous relationship is between Patek Philippe and Tiffany & Co. Their formal agreement started circa 1876 with a handshake between Charles Lewis Tiffany and Antoni Patek, and Tiffany & Co remains the only retailer worldwide allowed to dial stamp Patek’s watches with its logo.

Given their inherent rarity on an already supply-restricted market, examples that come to sale publicly achieve significant premiums. In 2019, Sotheby’s auctioned two Patek Philippe Reference 2499s in the same auction. Both came from the same original owner, who had taken delivery of them 11 days apart in July 1984, and both remained in matching superb condition. Going under Sotheby’s hammer an hour apart, the standard watch ended up selling for $450,000 while the Tiffany-dialled example went for $800,000.

Tiffany also used to retail Rolex watches, but the relationship ended in 1990, apparently acrimoniously. Again, retailer-stamped Rolexes sell at a significant premium to standard variants, often up to double or more if they retain their papers. Given such premiums and continued demand, it is no wonder that some unscrupulous forgers have taken to ‘recreating’ retailer logos on standard dials. So, how do you avoid these watches?

Firstly, buy from a respected seller, as recourse in the event that an issue is discovered is essential. Also, don’t expect the brands or retailers to have kept sales records; as a rule, they don’t (Beyer in Germany being an exception). Scrutinise any paperwork that a watch may come with, because the retailer’s details are often noted on the certificates or warranty papers. This isn’t foolproof, however; I’ve seen many badly added inauthentic retailer stamps on vintage papers.

Secondly, inspect the dial print under magnification. Retailer fonts used on Patek and Rolex dials vary greatly, and the location of the stamp is era and model specific. For instance, Patek stopped retailers from placing their logo above the Patek one c.1960; Tiffany had a habit of doing this. Also look for blotchy or sloppily applied text, and check the alignment. Retailers apply their names locally, using the décalque technique of transferring the ink from an engraved metal plate via a silicone stamp, so these are not always perfectly executed.

Also, check for case engravings. Tiffany usually scratched, and Argentina’s Joyeria Ricciardi often engraved, inventory numbers under the lugs, while Asprey (opposite) engraved its name on the case back. Serpico Y Laino did similar with its initials and a metal designation (18k, or ACERO for steel).

Another thing to check is that the retailer in question was both in business and an authorised retailer when the watch was first sold; I was recently offered a Rolex with the stamp of Cuba’s Joyeria Riviera; it was an early 1970s watch, years after the retailer closed. In general, if you have any doubts, walk away. But if you can acquire a good one, you will have one of the more storied, evocative and interesting niches in watch collecting.

Jonathon Burford is vice president and specialist at Sotheby’s watch department. For its ongoing Watches Weekly sales see www.sothebys.com.