WORDS: NATHAN CHADWICK | PHOTOS: GREG WHITE

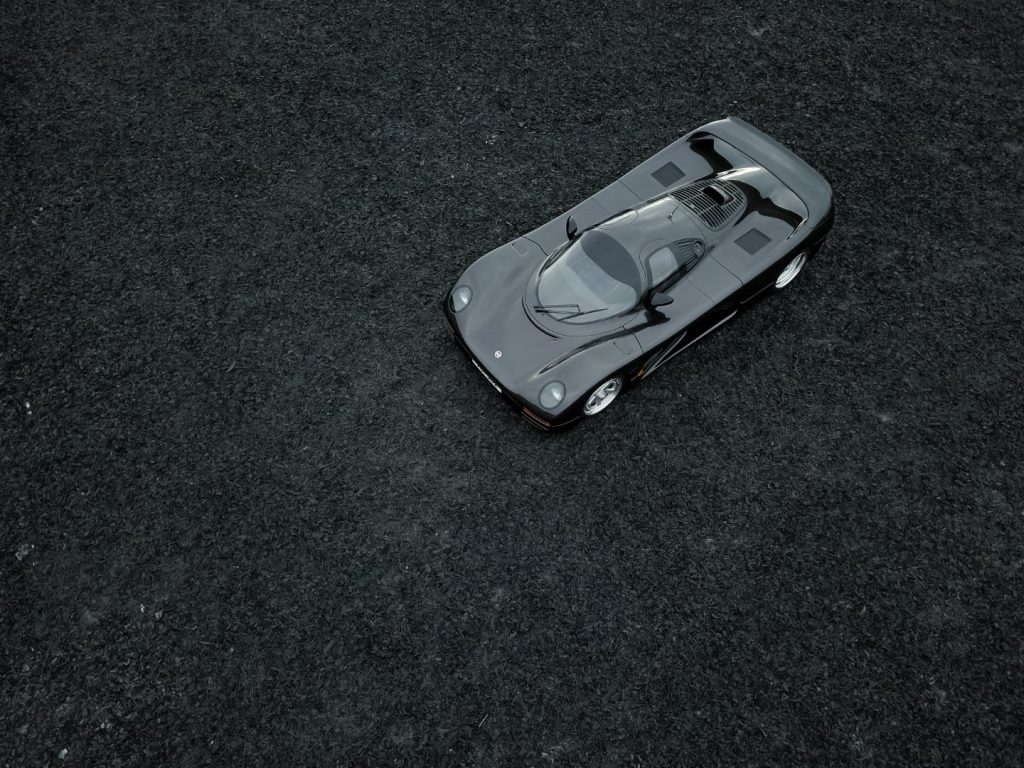

This year, one of just four remaining Schuppan 962CR road cars will make a headline appearance at the London Concours on June 6-8, 2023, leading a special supercar display. In issue 13, Magneto caught up with Vern Schuppan, whose victory at the Le Mans 24 Hours in 1983 paved the way for one of the most ambitious and controversial road-car projects ever undertaken.

This story originally appeared in Magneto issue 13

“People often ask me if I want one now – no, I bloody don’t!” A supercar with your own name on it – for every Ferrari, Lamborghini or Pagani, there are countless numbers of ‘one man, one vision’ passion projects that have started with dreams as lofty as the projected performance figures, only to turn into a waking nightmare for which the PR bumpf has had more mileage than the prototypes.

For Vern Schuppan, however, the prospects of self-named supercar success looked better than most. Although his career spanned Formula 1, USAC, IndyCar and touring cars, he’s best known for his exploits in sports car racing, particularly for Porsche. His 1983 triumph at Le Mans alongside Hurley Haywood and Al Holbert in a Rothmans 956 made him the first Australian to take victory in the event since Bernard Rubin in 1928.

He also won the All Japan Sports Prototype Championship the same year, making him a celebrity during the peak of Japan’s boom years, when conspicuous consumption was king. So when one of his race team’s sponsors knocked on the door in 1988 wanting a road- going Group C car for each of its 50 Japanese hotels… well, why not?

“Kosho, a part of the Nomura company, was building golf courses and hotels across Japan, and the man in charge of that division was a real racing buff, and came to all our sports car races,” remembers Vern. “He approached me about doing a street-legal, pure Le Mans car – to be called the Schuppan 962LM.”

By this point, Vern had already set up Team Schuppan in High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, UK to compete in the World, Japanese and IMSA sports car championships. Alongside this effort, Vern Schuppan Limited supplied services to other race teams and manufacturers. With Vern’s connection to Porsche and his contacts book filled with the cream of motor sport engineering talent, the omens were good.

The project began with the Porsche 962 driven by Brian Redman, Eje Elgh and Jean-Pierre Jarier to tenth place at Le Mans in 1988, which would be the mule car. The operation was being run out of the former Tiga factories owned by Howden Ganley. “I used to pop by to see how their project was progressing,” Howden recalls. “Vern asked whether I could help him out. I was burned out after selling out of Tiga, but my wife said, ‘you can’t play golf every day’. I thought, ‘why not?’ – but pretty soon I was doing two days a week.”

Having got the car through emissions standards, and the production moulds ready, disaster struck – the Japanese economic miracle shuddered to a halt and the demand for supercars began to contract. Kosho’s confidence in selling 25 to 50 cars was shattered. It was on the brink of pulling out, but what looked like a saviour appeared. A contact within Kosho, who had brokered several sponsorship deals for Vern’s team, had already got Art Sports (AS) colours on the car via Toshio Terada. “Terada had an elaborate showroom in Osaka, dealing in supercars,” Vern remembers. “It was a big deal to get the first of anything into Japan, so AS had in mind to take over what was initially supposed to be a pure road-going Le Mans-bodied 962.”

AS bought into the project in 1989, but there was a problem. “There was never any talk of changing the design – AS was quite willing to take over the 25-car order [from Kosho],” says Vern. “It was only when we were ready to start producing cars that it said that the longtail LM wasn’t very practical – it wanted to have a more GT-looking car.”

Because the prototyping and pre-production had already been done for the 962LM, AS’s list of changes meant starting all over again. It also wanted more interior space. This meant a brand-new, two-inch-wider chassis and a body to sit atop it; the 962CR was born, with the plan being to develop the 962LM alongside it. Enthusiasm was still high, and Vern had established a crack team. He’d already brought Ray Borrett to the UK from Holden, General Motors’ Australian outpost, for his long experience in prototyping cars. At Borrett’s suggestion, Vern garnered more Australian talent for the 962CR’s design. Alongside proposals from Ken Greenley and IAD’s Martin Read, Aussie Mike Simcoe would also put his hat into the ring. “Mike was the head designer for GM at Saturn in the US – when we looked at the three proposals, his was head and shoulders above the others,” says Vern. “He ended up flying backwards and forwards from the States working on the buck. He’d spend a week just rubbing down the buck, changing a radius here or there. He was fully hands-on.”

It was a frantic time that required plenty of on-the-hoof ingenuity. Recalls Howden Ganley: “Vern said we needed to get the master and the moulds done to get the prototype up and running, and asked me if anyone could do it. The only bloke I knew who would get on it right away was my old mate Bill Stone. [Vern would eventually take over Stone’s company to manufacture the bodywork.] It was an around-the-clock job up at Bill’s Bicester factory. Mike Simcoe came up for a long weekend and didn’t sleep the whole time he was there.”

Trevor Crisp, who worked on the project for two years as a mechanic, recalls it taking a lot of work to get the body to fit. “It was not that symmetrical to start with – I think one guy did the left side and another guy did the right. There was no thought gone into how all the panels were going to be fixed on the car or hinged. I basically got a scribble on a cigarette packet from Howden: ‘We need something this kind of shape, that’ll bolt on like that, we’ll draw it up later.’

“I just went off and made the rear beam, which to Howden’s disgust was a welded-together fabrication. He asked why it wasn’t folded and riveted like a chassis, but I said I’d only had two days to do it. Unlike the prototype, the production cars were nicely riveted, a bit like a sheet monocoque chassis. That’s generally how a lot of parts on the car were developed – you would find a solution, and then it’d go to the drawing department to be sketched and refined.”

Howden picks up the story: “I designed the large structure, which is very light, to be a feature and make it look as though somebody had really thought it through. I was delighted with the result, and it is still on the car.”

The team was already under great pressure, but it didn’t stop persistent meddling from AS and Terada himself. “They’d fly over or send us drawings with changes, such as the shape of the exhaust – more oval or a little more square,” Vern recalls. “It was a host of little things like that; each change would set us back.” The 962CR prototype was finished within 18 months, but then things started to go wrong. “Car Graphic had been following the project, and when we finished the prototype AS brought the magazine over to the UK,” Vern remembers. “We had a big launch in the factory in 1991, and ran the car on the banking at MIRA, more for photographs than anything.”

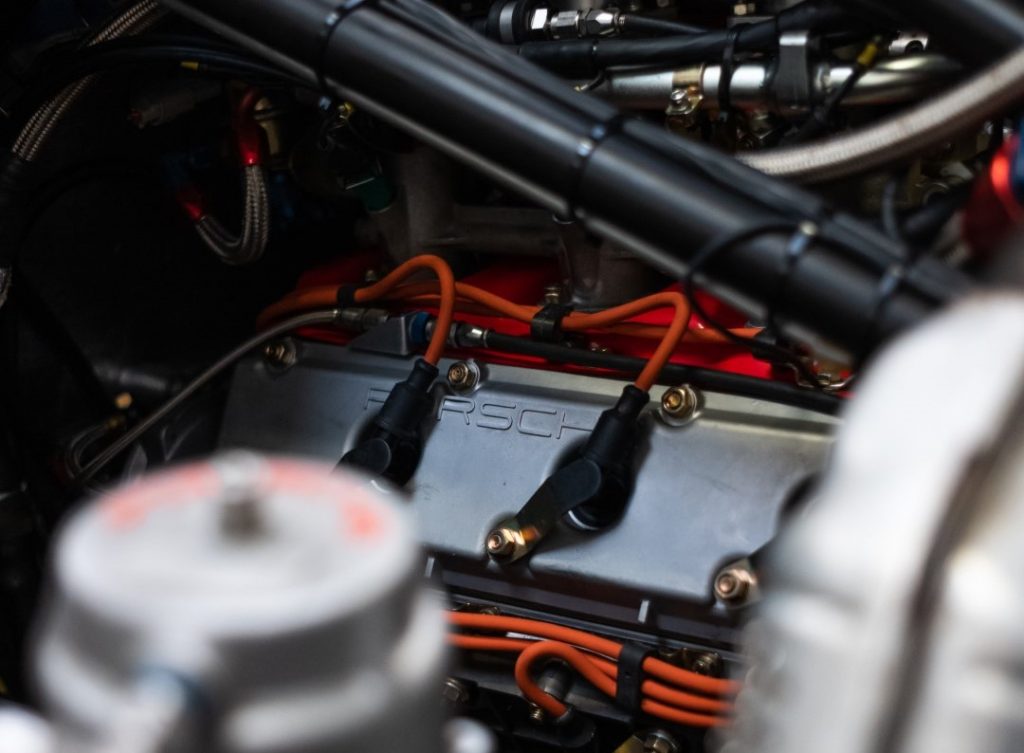

The day after the MIRA shoot, the car was packed up and sent to Japan. “Unbeknown to us, AS had taken our Schuppan badge off and put a Porsche badge on,” says Vern. “When it showed the car in Japan, and in the Car Graphic article, AS claimed it had worldwide rights on this ‘Porsche’ supercar. Porsche was livid. We had a contract for 25 water/air engines, and had received five, but after the article it wouldn’t supply us with any more parts.”

Vern then turned to Andial, who’d prepared Porsche’s cars for the IMSA series, to provide the engines. The aircooled, twin-turbocharged 3.4-litre flat-six produced between 500bhp and 600bhp. Thanks to a carbon-composite body and a Reynard-built carbon monocoque (for the production cars) that in all weighed 1050kg, performance was brisk, with a projected top speed in excess of 215mph. Unfortunately, the project was about to go pear shaped as quickly as the 962CR could accelerate.

“In 1992 I was passing through Japan on the way to Daytona, and I had a meeting with AS just before boarding the plane. The bombshell was just dropped,” says Vern. “Terada wasn’t in the meeting; it was the head of finance. They had decided to can the project because they hadn’t sold the 25 cars.”

A shell-shocked Vern managed to negotiate ten cars, the minimum needed to keep the project going, to which AS agreed. “Then AS decided to take just three – it was almost impossible for us to remain in business and build those cars, but we did it,” Vern recalls. “We did it on the condition that AS issue letters of credit for the three cars, which it did.”

Howden adds: “When I was given the responsibility of building that last car [CR04, the one you see before you], we just got on with fixing any problems. It was a killer effort – I was 95 percent happy with what we’d achieved. We put it together in less than a month.”

“I don’t think AS thought we could do it, so when the cars were finished it came over to the UK to inspect them,” says Vern. “If AS cancelled the contract there was a £6 million clause – so its people brought their lawyers over with them, and started picking out faults with the car.”

“They claimed that the car would overheat if they ran it for more than five minutes,” recalls Howden. “We started it up, and it ran for 25 minutes and didn’t overheat.”

Cars CR04 and CR06 (the ADA-built LM with the CR rear bodywork) were due to go on a British Airways flight to Japan that night, but the AS lawyers called an emergency High Court session. That was postponed until the morning after, yet the cars had already been loaded. The judge gave AS the right to make further inspections, and ordered the cars to be unloaded, but by this point the aeroplane was full of passengers and heading out onto the runway – British Airways declined to bring it back in.

“As soon as the ’plane took off, AS’s lawyer was straight on the phone to Barclays, saying it couldn’t cash the letters of credit because I was in breach of a court order – something that was impossible for me to fulfil,” Vern remembers.

While CR06 and CR04 were en route to Japan, AS got another court order preventing Japan’s border agency from offloading them. They sat in storage at Narita airport for months before Vern Schuppan Limited managed to fly CR04 back home.

Matters soon got worse. Vern had taken out a personal loan to buy the 60,000sq ft factory necessary for the project and part funded by AS. If Vern Schuppan Limited failed, AS could call that loan in within 14 days. “We had a huge number of suppliers, and we simply couldn’t pay the bills,” explains Vern. “The hardest thing to face was telling the many people working on the project they didn’t have jobs anymore – I was getting hate phone calls.”

Undeterred, Vern chose to fight AS at the High Court. Work on converting the factory stopped, and production returned to Howden’s buildings. “The first big law firm we talked to told us to sell everything and see if AS would settle,” Vern recalls. “I said I’d rather sell everything and fight it.”

The court case was set for two weeks, but the AS lawyers applied for two months. “The judge settled on five weeks, and I had to find £260,000 extra as security against court costs,” Vern says. “I had to put up my Martini Lancia as collateral, which was accepted as enough to cover it.”

This was only the beginning of the pain. “These lawyers were putting people outside our house, phoning at 2am in the morning, waiting till Friday night to send 30-page faxes of what they were going to use against us the next week. They had someone sat outside my gate at all times, ready to serve me papers.”

Suspicions were strong that there was a mole inside the factory, or at least close by. “It seemed they knew an awful lot about what was being said in the office,” Howden recalls. “I’d noticed a different car parked across the road from the factory every day – I said to Vern, maybe there was a radio-listening device in it.”

The breaking point came when they came for Vern’s house in Berkshire. “We had completely rebuilt it, and the kids had ‘designed’ their own rooms – it’s unbelievable how they and my wife Jennifer managed to cope,” says Vern. “One day we were walking the dogs, and my son turned to me and said that at least we had each other.”

Although Howden Ganley wasn’t part of the management team, he did sit in on some of the High Court sessions. “I was once told by a barrister that even the best case in the world has only a 70 percent chance of winning,” he muses. “Vern had a 100 percent watertight case – I couldn’t believe he lost it.”

At the time, Vern had been offered a job running Stefan Johansson’s Indy Lights team in the US. “We’d run out of cash, and Jennifer and I both thought we really needed a complete change, so we’d decided to move,” says Vern. “I went over pretty quickly, while Jennifer had to stay back and go to court every day while the house was being snatched. Even the judge apologised for the way she was being treated.

“They waited five days until Christmas Day to serve bankruptcy papers on us,” he recalls. “An old pal phoned and said, ‘look, you have to come to some kind of settlement, or it’s going to wreck your marriage or kill you’.”

The opposing side’s barrister intimated that AS was looking to settle, and Vern’s house in Portugal was the prize. “We had to pass all the deeds over unless we could come up with the settlement AS was looking for. If I could make this payment to the creditors, my bankruptcy would be annulled – and that’s what happened.”

With the court case wrapped up, Vern focused on his new life in America. The factory and its equipment were sold, and eventually a UK buyer bought chassis CR04. It has never left the UK since then, but it did appear in Alain de Cadenet’s Victory by Design TV programme.

It was then bought by a windscreen firm boss, who commissioned Group C Ltd to undertake modifications to make it more usable. In 2006 Group C Ltd under Trevor Crisp’s direction performed a host of changes to meet UK single- vehicle type approval. At time of writing it has covered just 35 road miles and is now up for sale with Maxted-Page.

The factory was bought by an automotive PSV glass distributor. In 1997 former ADA director Chris Crawford set up Group C Ltd with Trevor and two other ADA employees in a portion of the same factory to restore 956s and 962s. Following the closure of Group C Ltd in 2012 and with all the assets sold off, Trevor set up Katana Ltd, and has restored seven of the works Rothmans chassis. In the end, just four 962CRs were built.

Understandably, Vern was happy to wash his hands of the project. “They broke me. Going to the US was the clean break that saved us. However, I’m still sad that, as well as our own staff, our suppliers and creditors suffered terribly from our inability to repay them.”

Howden’s still a fan of the car. “The steering was light, the gearchange was good – the ’box had synchromesh, which was perfect for a road car, unlike some other supercars of the era that used straight-cut racing gears. The engine would pull from nothing, too. I took LMs to the supermarket to demonstrate you could go shopping with them, and you really could. It’s so usable, that’s what makes it. It’s very tractable and very quick – it’s just a magical car.” Thanks to Lee Maxted-Page (www.maxted-page.com), Trevor Crisp (www.katanaltd.com), Vern Schuppan and Howden Ganley.