Words: David Lillywhite | Photography: Praga

Romain Grosjean is sat in Praga’s new road-legal Bohema track car, making himself comfortable again for a second day of testing at the Slovakia Ring track. He jokes about the scars on his hands, a result of his horrific accident at the 2020 Bahrain F1 Grand Prix, grins like a schoolboy when the team laugh about his on-the-limit driving, but goes all serious when he’s talking about his input developing the car that he helped to inspire.

“When I was driving it, if I hadn’t looked down to see that I was wearing jeans, I wouldn’t have remembered I was in a road car, because it really behaves like a race car – more like a single-seater in fact, because there’s the aero and the downforce. I was driving it thinking ‘this could be a prototype, I could actually be testing to go to Le Mans’. And then you come into the pitlane and drive it away on the road. It’s amazing!”

So, Praga? There’s a fair chance you’ve not heard of the company, or simply have a dim recollection of it as a name from the distant past. In motor sport though, it’s a brand that’s been growing in stature over the past two decades – first in motocross, then karting and Dakar Rally trucks, and since 2012 in modern sports car racing around the world with the championship-winning R1.

With the success of the R1 race car, the obvious next step seemed to be a road-legal, track-focused model, which is what Romain and others challenged the Praga team to attempt. Initially, it tried converting the R1 race car to road spec, resulting in the 2016 R1R, but the team wasn’t happy with the compromises needed, and started to develop an all-new design – which we now know as the Bohema.

Thankfully it’s not ‘just’ another hypercar, with the ever-increasing power and weight that goes with that territory lately. The Bohema’s focus is all about light weight rather than ultimate power, and that makes for uncomplicated, basic but high-performance thrills on road and on track. We’ve been following its progress for the past couple of years, intrigued by the 115-year history of the brand, and taking early rides in the prototype – most recently alongside Grosjean – during the past few months ahead of this week’s big reveal.

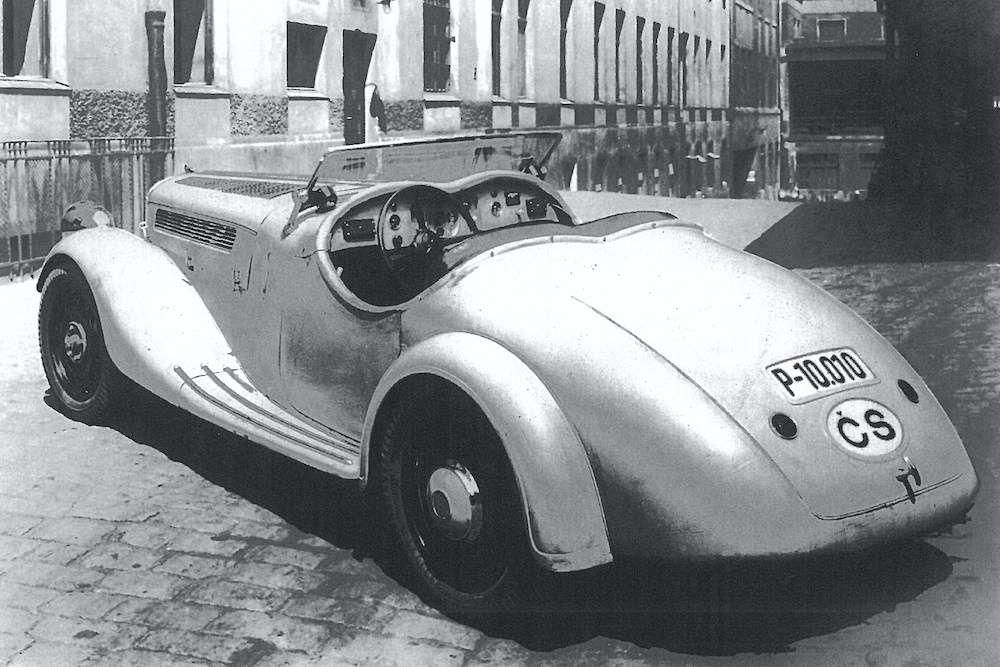

So a brief history lesson to set the scene: Praga, named after – and always based around – Prague, has its roots in a heavy-engineering company of the late 1800s. It built its first cars in 1907, initially as licenced copies of Isotta Fraschinis before developing its own models. By the mid-1920s it had a sizeable range, and in 1933 one of its six-cylinder Alfa models won the inaugural 1000 Miles of Czechoslovakia road race.

Alongside the cars, Praga was also building tough, go-anywhere trucks, which became its focus from 1947 when Czechoslovakia’s new Communist government instructed the brand to leave car building to Skoda and Tatra. It wasn’t until the fall of Communism that Praga was able to set its own agenda again, which came with its own problems after years of being state run. Eventually its new private owners introduced motocross bikes alongside the venerable trucks, then bought a kart factory, which has since grown to such an extent that Praga now makes more than 7000 chassis a year.

With an aero division as well, the company finally went back into cars in 2012 with the V8 R4S, quickly followed by the more race-focused Renault Alpine four-cylinder-powered mid-engined R1, for which there is now the popular Praga Cup as well as eligibility in sports car racing worldwide.

And so we come back to the new Bohema, which Praga’s small team of engineers and designers have been working on for the past five years. It’s a composite monocoque, designed with aerodynamics and light weight foremost in priority – the Bohema weighs just 982kg. Suspension is by race-style pushrod-operated horizontal dampers, braking by carbon-ceramic discs and six-piston calipers, and the engine is a Nissan PL38DETT twin-turbo V6, as used in all GT-R models since 2007.

Praga buys the engines new from Nissan – a unique deal – and ships them to the renowned Litchfield Engineering in the UK to be rebuilt with a dry-sump system (allowing the engine to sit lower in the car), stronger turbos and other mods that are expected to unleash 700bhp or more, depending on the specification chosen for the final production models. The car you see here is one of the prototypes.

On a rainy day in May 2022, I first experienced the then-camouflaged Bohema prototype at Praga’s UK HQ in Cheshire. A brief test on wet, bumpy local roads revealed startling performance, a lot of mechanical noise from the famously tough Hewland sequential transmission, and a remarkably good ride – not just by track-car standards, but compared against any modern performance car. It was clear that the light weight was complicit in the surprising ride quality and the ballistic acceleration. If there’s anything that really gave away the track focus, it was the lack of subtlety of the paddle-shift gearchanges, which felt violent under hard acceleration.

Praga had realised from its R1 experiences that some of its customers wanted track cars but felt daunted by the basic, aggressive feel of pure racers. The Bohema manages to keep on the just-civilised side of a competition car mannerisms, despite the compromises brought about by the dedication to extreme weight saving and aerodynamics.

To climb into the cabin, you swing up a tiny lightweight door, sit on the wide side pod and swing your feet into the footwell, using neat steps moulded into the carbonfibre tub to ease yourself down into the seat. The steering wheel is removable to ease the task, and picking it up off the passenger seat to refit onto the column gives a chance to admire the engineering that’s gone into the wheel alone – it’s tiny but weighty, with full digital display, indicator and wiper switches, and neat mode-selection dials all built in. As Romain points out a few months later: “A steering wheel is one of the hardest parts to design in a race car. Everyone has different hands – and mine are burned! – but the ergonomics of this are really good.”

There are various clever pockets and storage areas inside (plus luggage areas in the exterior pods), and the trimming in Alcantara and leather is to a really high standard. The same goes for all the neat cast and 3D-printed metal components, such as the sprung cradle that holds a smartphone for use as sat-nav or data-logger. Air-con controls are in a tiny roof console, and doors are released using an electronic release button, although there’s a mechanical release in the roof in case of failure.

On that first experience, it was clear that two adults can sit in the Bohema without feeling cramped, thanks to the long footwells and sculpted cut-outs for the passenger’s elbows and forearms. For the driver, seat angle as well as pedal box and steering-wheel position are all adjustable. Even at speed it’s possible to talk normally, although the sharp exhaust and throaty intake soundtracks intrude under heavy acceleration – this isn’t a quiet car, but it’s not uncomfortable.

On my second visit, this time to Prague, I get to see the more finished version, resplendent in blue metallic, and hear more of the history of the brand from lead engineer and Praga authority Jan Martinek, who grew up in the shadow of one of the mighty Praga truck factories. The decision has been made to offer 89 examples of the Bohema, each made to customer specifications, for £1.1m (€1.28m) each. Why 89? Because it’s 89 years since that historic, marque-defining victory in the 1933 1000 Miles of Czechoslovakia race.

It’s clear on that visit that the levels of finish are high, a result of final assembly and set-up being the responsibility of former WRC rally driver Roman Kresta at his obsessively clean Kresta Racing HQ, following development work there of the R1 race cars.

My third visit is to Slovakia Ring, where former F1 and now IndyCar racer Romain Grosjean has been busy on-track in one of the Bohema prototypes. Time is tight, and I have the choice between driving a couple of tame warm-up laps or getting the full flat-out experience with Romain. What would you do? I opt to be a passenger, and Romain is off, the wide smile gone, concentrating hard as he slides the Bohema around the twisty circuit.

At these speeds, the aero comes into play – up to 900kg of downforce at 250km/h. As with any aero car, this makes for otherworldly cornering speeds, but Romain is able to slide the car, catch it quickly, accelerate hard out of every corner and brake heavily into the next time after time without any sign of the car suffering. No soft brake pedal or smells from hot pads here.

“It’s really balanced on entry of the corner, then a little bit understeery mid-corner,” says Romain afterwards, which corresponds with Praga development driver (and former F2 and F3 racer) Josef Král’s policy of setting up the car to be exciting but safe for less experienced drivers.

“There isn’t 1000bhp, but on exit it’s good because of the power-to-weight ratio,” continues Romain. “It’s got good traction, but you need to manage your throttle, otherwise the traction control comes in, although it’s very subtle. It [the traction control] is quite late; I like it. It’s not like it stops you. We’re discussing different traction control maps and how many maps they want to use. Maybe two… Race and Race!

“Braking has been really good. There was a bit of vibration, but this is a car that has been pushed to the limit. I was out for six, seven, eight laps at a time, really pushing it, so I was amazed at the brakes; the pedal doesn’t go, and that’s the first thing that goes in many cars when you’re on a race track. But not in this car! If I’m really picky here, the ABS could be slightly fine tuned, although it was the first time it had been run with the ABS on track.”

He continues: “Maybe the gearbox on the road could be smoother, too. On track, it’s really good, but it needs a map for the road. It’s just a question of the ramp and the cuts to the ignition before it re-engages the clutch. These are the fine details that they’re going to get onto.”

A couple of weeks later, the prototypes are back in the UK, this time in the hands of the former Stig, Ben Collins, at the Dunsfold aerodrome better known as the Top Gear test track. Ben carries out a full assessment of the Bohema, which he summarises with this: “Fabulous car! I’m actually missing it. Overall the car is really addictive to drive fast. I don’t know of any other super/hypercar that you drive relentlessly, without any mercy, until you run out of fuel, and then do it again.”

Personally, I’m looking forward to driving not just the production version next, but also some of Praga’s historic models. There’ll be more of those in the next print issue of Magneto, out in early February 2023.