WORDS: ELLIOTT HUGHES | PHOTOS: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

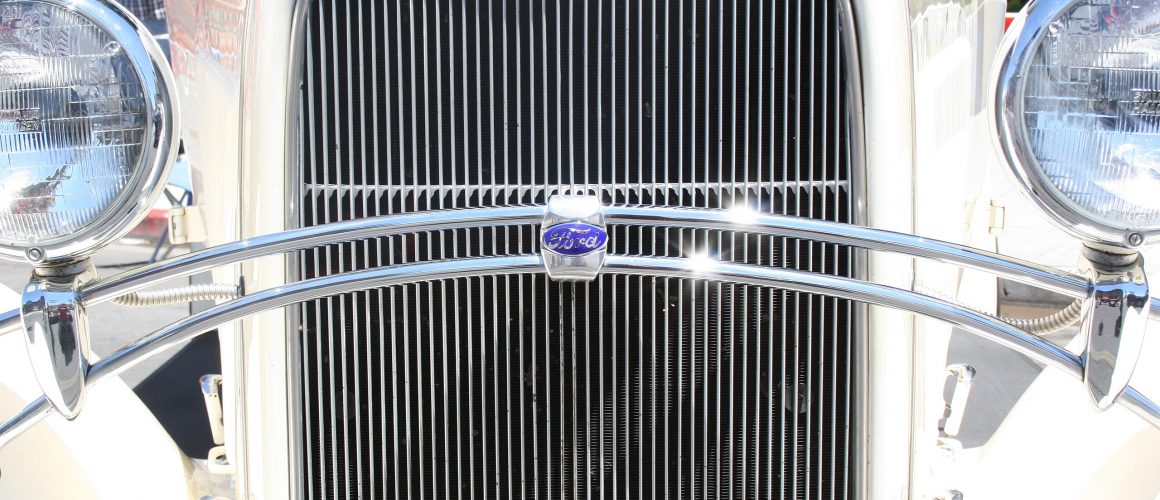

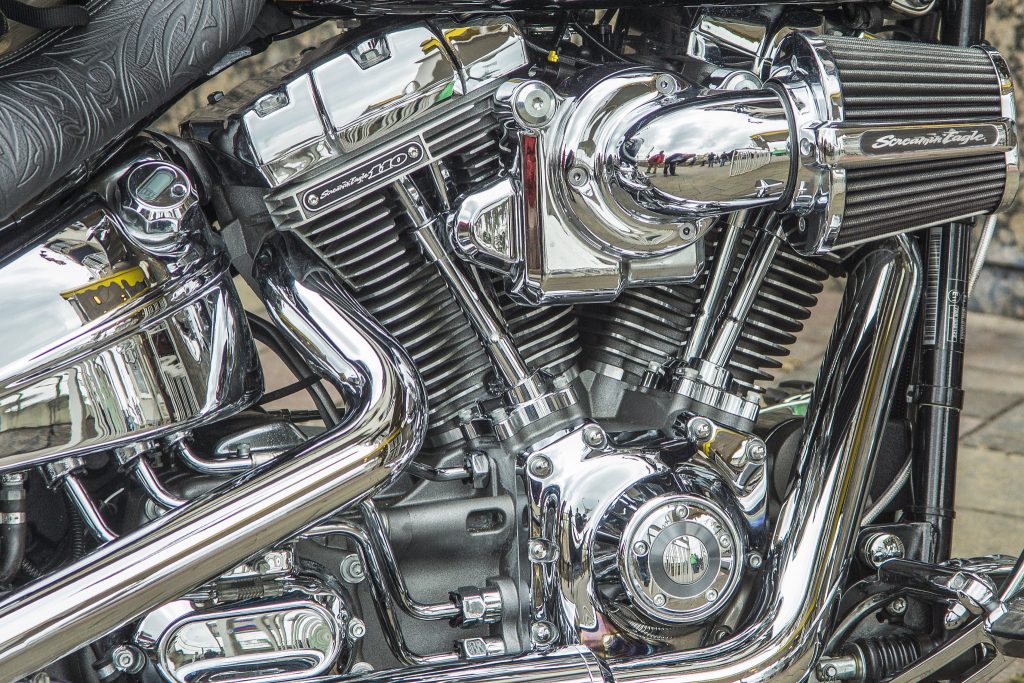

Lustrous chrome has been a staple of glitzy automotive styling ever since Colin Fink and Charles Eldridge developed a commercially viable plating process at Columbia University in 1924.

So it is not surprising that articles in the new-car press on the EU’s ostensibly contentious decision to outlaw chrome plating in 2024 over health and environmental concerns has raised more than a few eyebrows.

An outright ban on chrome plating would have consequences that extend far beyond the classic car world, as the material is prevalent in products ranging from kitchenware and light fittings to aviation components and firearms.

An outright ban on chrome plating would have consequences that extend far beyond the classic car world

News of the EU’s proposed ban follows a similar yet more drastic move by the California Air Resources Board (CARB), which intends to ban hexavalent chromium in decorative plating by 2027. More significantly, CARB’s ban also prohibits hexavalent chromium’s use for industrial durability plating commonly used in aerospace, by 2039.

According to CARB, the ban is necessary because harmful emissions from the plating process disproportionately endanger the health of people living in disadvantaged communities. The gases emitted during hexavalent chrome manufacture have been found to be 500 times more toxic than diesel fumes. Harmful emissions from the process can be lessened by chemical depressants, but these contain Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), which are also highly toxic and have been irresponsibly released into waterways.

Significantly, the impact of the EU’s own intended legislation on decorative chrome plating in the automotive industry is lessened by the existence of an alternative process, known as trivalent plating. This means that the notion of the EU banning chrome plating outright is a red herring.

Magneto spoke to Nottingham Platers director Simon Revelle, who explained that his company was the first in the UK to master trivalent chrome plating:

“My father-in-law set up the company in 1982. He was a qualified chemist, and heard about trivalent plating after it was developed in the US. He knew that at some point, hexavalent plating would be banned because it isn’t very environmentally friendly, so he took a gamble and decided to have a go at trivalent plating. It took him two years to master the finish, and at one point he nearly decided to give up and go back to hex chrome.

“Switching to trivalent was a risk, because it’s a totally different process that requires new equipment and a completely different mix of chemicals. The government has talked about banning hexavalent for years, and now they’re finally doing it. So chroming companies are either switching to trivalent or they’re going to stop chrome plating altogether.”

In other words, if the legislation passes, companies will be forced to invest significant sums of money in new chemicals and equipment, as well as being required to master a completely different process. For consumers, there will be a few consequences.

The first is cost. Trivalent plating is more expensive than the traditional hexavalent method. “We pay about £1000 a week extra in chemicals, but that’s the cost of being more environmentally friendly,” Simon explains. That said, some of the extra cost is offset by the fact that the trivalent plating requires less energy, while the reduced amount of harmful by-products are easier to dispose of.

More controversially, there is also a slight cosmetic difference between hexavalent and trivalent chrome. The chromium deposits produced from hexavalent electrolytes appear silver with a subtle blueish tinge, while those formed from trivalent chromium baths typically have a subtly smokier appearance. Even so, Simon explained that it is also possible to introduce various chemicals that can alter the appearance of trivalent chrome finishes:

“My father-in-law developed several trademarked finishes. He was messing about with chemicals one day, and came up with a duller chrome finish that mimics the appearance of stainless steel. We can also replicate mild steel that’s a third of the cost to the customer.”

The main drawback of the trivalent method is that it can’t yet be used to manufacture the hard chrome required for aerospace components, for example. This, however, is largely irrelevant in the context of automotive styling, as large manufacturers can simply make the switch from hexavalent to trivalent chrome once the ban is enacted in 2024. Aerospace firms, meanwhile, could well be given special exemptions that allow them to continue to manufacture hex chrome until a viable alternative is developed for certain components.

Those hardest hit by the legislation will be small chrome-plating firms without the means or expertise to switch to an entirely new manufacturing method.