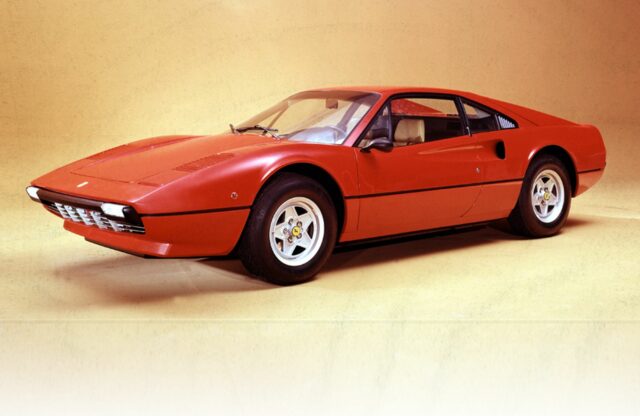

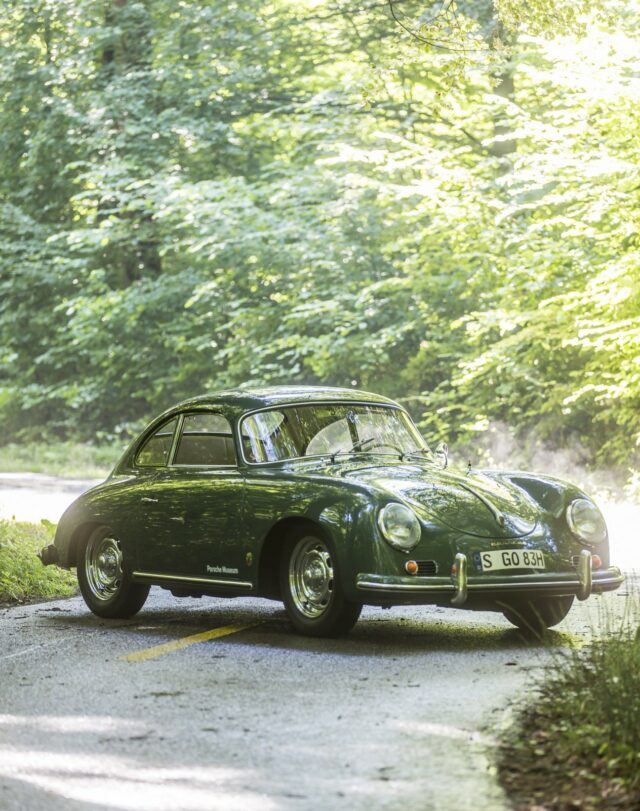

To denigrate a Porsche 356 as ‘an uprated Beetle’ is to sell the whole car short. Fastidiously honed during a 17-year run, it prepared the ground for the 901/911 series that moved the German manufacturer into the big league of volume sports-car production.

It was a slow job to get the first 356 – named for the engineering consultancy’s 356th project – off the ground in 1948; Porsche’s factory was occupied by US troops, and Germany was still reasserting itself economically. The firm had begun to crystallise its ideas for a lightweight sports car before World War Two; the very first 356/1 was built on a spaceframe.

Realising that series production would demand a simpler method of construction, Porsche built 356/2s out of an inner/outer monocoque whose floorpan resembled (but differed from) that of the Type 1 Beetle. The consultancy fees for the VW model would fund future 356 development.

To denigrate a 356 as ‘an uprated Beetle’ is to sell the whole car short

Box-section sills, a central reinforcement tunnel and strong bulkheads fore and aft moved the 356/2 away from the Type 1. Even its engine and transaxle, thoroughly revised with bigger heads and re-angled valves, was turned through 180 degrees.

As Germany’s economy improved, so did Porsche’s prospects. While the last Austrian cars were completed in 1951, a year earlier the firm had moved into the factory of Reutter, a renowned Stuttgart coachbuilder that would later produce the lion’s share of 356 coupé bodies. Other coachbuilders, such as Drauz, would help build cabriolets, a bodystyle that had been a 356 mainstay since production began.

Evolution was fast and frequent; between 1955 and 1957, the retrospectively named ‘pre-A’ series was discontinued and the first 356A Type 1s were produced. Flat-four engines, of both pushrod and four-cam variety, to Porsche’s own design, grew from 1100cc to 1600cc via 1300cc and 1500cc variants; the four-cam Carreras, in 1500cc and 2000cc form, are outside the scope of this guide. In 1955 the limited-run, rakish Speedster was introduced – a cut-down cabriolet now accessible to only the wealthiest of collectors. And 1957 saw the 356A T2 revision arrive, with reworked doors and trim, and cabriolet quarterlights.

The 356B was launched in 1959; production had really ramped up by this stage and this was the most plentiful of the model. There were very few interchangeable VW parts left on cars by now – the rear trailing arms, halfshafts, crown wheel, pinion and differential housing were all that were carried over.

Porsche didn’t use the T3 or T4 designations, so Bs were known as T5s, picked out by their raised headlights plus bumpers fore and aft. Quarterlights finally featured on the coupés; T5s lasted until 1963, when the final T6 variant of the model, the 356C with a larger, squarer rear window, was unveiled. The newly renamed 911 was looming large, but the old model was upgraded with four-wheel disc brakes.

By 1965, precisely 76,302 examples had been made – the last ten cabriolets delivered to the Dutch police. Uncannily attractive, precisely built and dynamically capable, the 356 did more with less, winning Porsche a legion of fans.

ENGINE AND GEARBOX

Mick Pacey, owner of Bedfordshire-based specialist Export 56 expects that most 356 engines will have been rebuilt by now. However, he warns new recruits to leave the four-cam engines to the most serious of collectors: “I doubt there are many first-time buyers willing to jump in at the deep end with the four- cam (Carrera); those engines cost tens of thousands of pounds, and are very complex race engines,” he says.

For the most part, spares availability is very good – but the earlier you go, the harder it is to find components, ruling out the pre-A cars for all but the most dedicated. Mick urges anyone to inspect the history files of a potential purchase and check just who has done the work.

Any general concerns? “They’re quirky engines and complicated mechanically. They all have a tendency to shed some oil. End-float wear (at the crankshaft) also needs to be checked,” says Mick. “They tend to suffer from engine fires, too; the alternator/dynamo, voltage regulator and carburettor[s] are all pretty close to each other on the right-hand side under the bonnet; there could be evidence of a fire on the right-hand bank of the engine.”

New carburettors and/or rebuild kits – Zeniths for the lower-powered models and Solexes for the faster machines – are available, but tuning and setting them up properly is a laborious task. Gearboxes are pretty robust; rarely are there any issues. Pre-A ’boxes were a little clunky, but as power increased they rose to the task. A lot of the problems people initially encounter with Porsches is the location of the motor and transmission; being rear engined, there’s some distance for the gear linkage to travel to the driver and stick. If it feels like the change is sloppy, it’ll be down to worn nylon bushes in the ’box couplings rather than anything inside the transmission itself.

Synchromesh units were introduced between 1952 and 1953; parts for earlier set-ups are hard to source.

SUSPENSION AND BRAKES

Wear occurs in the front kingpin and rear arm bushes, while dampers can also suffer from age. Steering boxes, which were originally Volkswagen derived, were later replaced with a Porsche-designed ZF unit; both are adjustable, but make sure they haven’t been ‘corrected’ down to the last shim and are simply worn out.

Drum brakes on pre-A, A and B models are more than up to the job, provided they’re not neglected. Heat build-up can crack or warp their alloy casings and cast-iron linings, and their scarcity is borne out by the preferences of specialists to refurbish these units rather than replace them. Later, disc-braked Cs give little trouble; their parts are often used as the basis for which to uprate earlier 356s. “Just check everything that you normally would on any old car,” advises Mick.

BODYWORK AND INTERIOR

“The metalwork can kill a 356; the biggest single drama is the bodyshell,” says Mick. “You can easily spend £100k restoring a ’shell if it’s knackered. Panels are expensive. It’s not one part of the body – it’s all of it.”

Specialists such as Roger Bray, PR Services and Karmann Konnection do have repro panels and parts, but none of it is cheap. Right-hand-drive cars were made in tiny numbers for the UK; their specific parts, such as dashboards, may not be easy to find if they need replacing. It all gets easier from the B onwards, because as it is the most common of all 356s, a big enough parts network exists to make a viable used market, in both Europe and the US.

The arches and door edges are vulnerable, as is the area under the front-mounted fuel tank. Mick says: “The bodies are a complex monocoque; anyone who says ‘the 356 is just a Beetle’ couldn’t be further from the truth. They are a body-within-a-body, and you can only get to the inner body by cutting the outer panels away.”

He continues: “There isn’t a front wing as such; it’s all undulating curves into other curves. The only removable panels are the doors, bootlid and bonnet. You have a front nose section and a front wing and a rear wing section; they’re all welded together and lead-loaded to get the shape right, and there’s no adjustment at all.”

Replacement cabin parts are available for most models, but the pre-A and A are more difficult. Not all repro seat covers are made to the correct style, so compare them with images of original cars. Radios are sought after, but again check that they’re the correct type for the model.

WHICH TO BUY

A good convergence between mechanical refinement, styling and price, the 356B T5 – in left-hand drive – would be Mick’s choice for a first-time buyer, owing to good parts availability and survival rate.

He says: “Porsche built over 30,000. Anything pre-A, or right-hand drive, will carry a premium; not many were made. The B T5 is attractive, with a nicely curved bonnet and smaller screen. Porsche also introduced a Super 90 model; they are drum braked, but these work incredibly well because they’re nicely engineered.”

WHAT TO PAY

UK (1964 356C 1600 Coupé)

FAIR: £43,400

GOOD: £60,000

EXCELLENT: £84,500

CONCOURS: £111,000

US (1964 356C 1600 Coupé)

FAIR: $53,000

GOOD: $79,000

EXCELLENT: $125,000

CONCOURS: $168,000

SPECIFICATIONS

1.6-litre flat-four

Power: 60bhp

Top speed: 103mph

0-60mph: 14.1 seconds