Writing a book about a particular design project of mine felt a little strange – mostly because my craft is designing and not writing, but also because the JaguarSport XJR-15 isn’t one of the better-known sports cars of the 1990s.

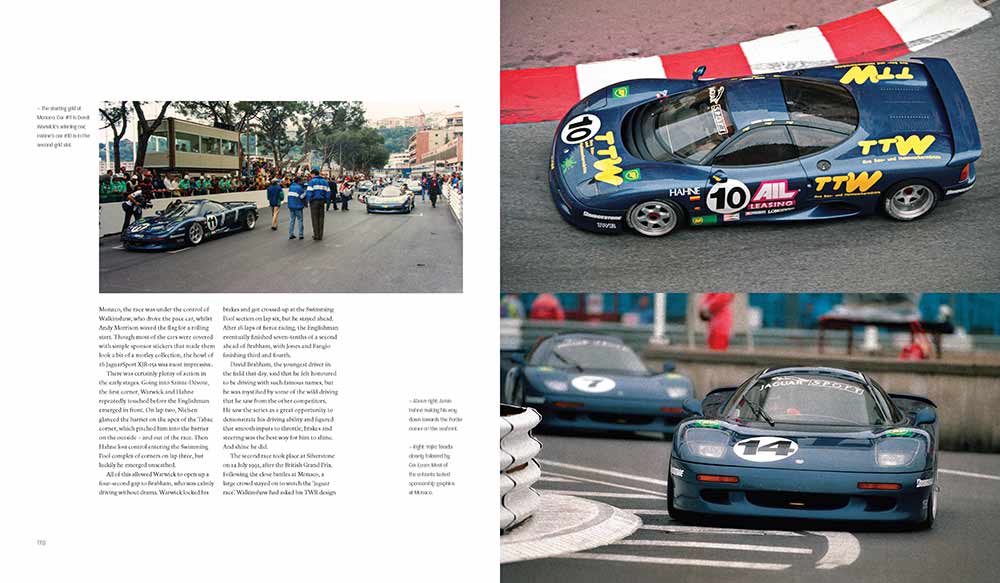

I decided that the tome should be a ‘personal account’, rather than a dry academic work full of chassis numbers and gear ratios, although constant reference to “53 cars built” in virtually every magazine article and online comment frustrated me. So, I should say right now, there were 50 JaguarSport XJR-15s and two TWR R9Rs built.

Much to my surprise, I found that I’d kept a huge number of notebooks, aerodynamic records, sketches, magazines and photos

I didn’t ask writers that I know how one should go about writing a book. And while there are probably many guides on the internet, then my work would not be ‘personal’. The Covid lockdown looked to be the perfect opportunity to concentrate on the book, but – as many people probably found out – there actually seemed to be little time to devote to luxuries such as writing.

However, Porter Press’s Philip Porter persuaded me that when the world had returned to a degree of normality would be a good time to start. Much to my surprise, I found that I’d kept a huge number of notebooks, aerodynamic records, sketches, magazines and photos. But during the past 30 years, virtually nothing complete had been written about the XJR-15 project.

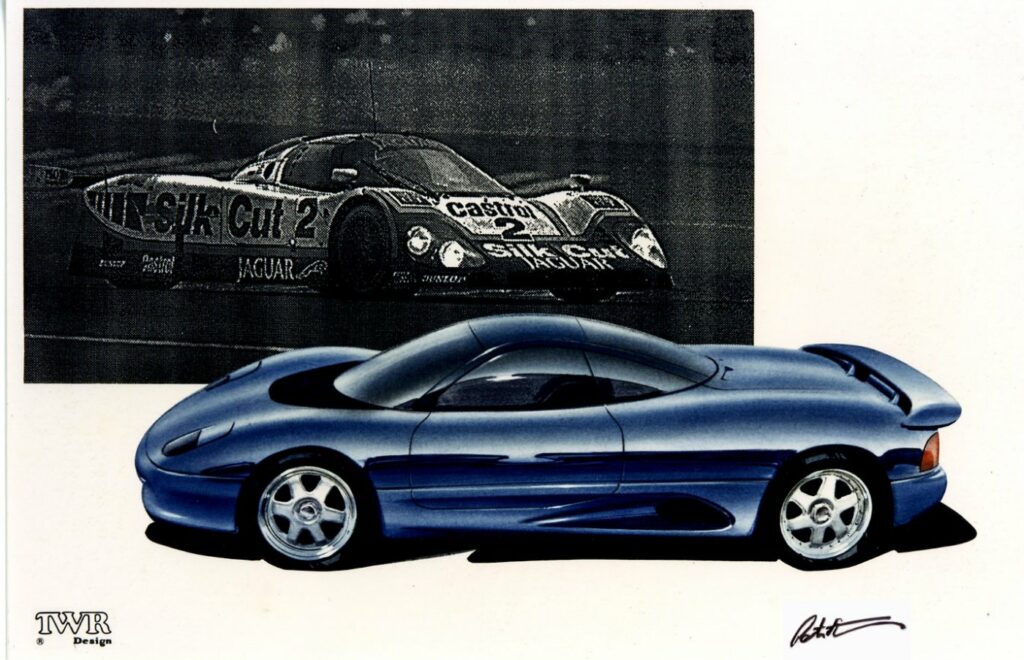

The XJR-15 was designed partly while I was still at Lotus, but dying under the General Motors regime, and, towards the end of the project, when I had joined McLaren Cars to work on the F1. It was at a turning point in my career, when my sketching method had changed as an escape from the Italian school of folded-cardboard designs to more organic forms.

TWR founder Tom Walkinshaw had decided, following a suggestion from right-hand man Andy Morrison, that after Jaguar’s historic 1988 Le Mans win it’d be interesting to build a small number of XJR-9 Le Mans cars for the road. His team had tested a race car that was set up for the road, with ride height and lighting to meet regulations. Not surprisingly, it looked awful. Having worked on other TWR projects, this was where I came in. Walkinshaw asked me for ideas on how the car should look.

The book gave me the opportunity to explain how the car came about, how we achieved so much in one year, my relationship with Tom and how he managed the tough situation he found himself in when his firm was asked to design, engineer and manufacture the Jaguar XJ220. I was also able to show, for the first time, one of Tom’s possible solutions for this dilemma, and clarify his masterful leakage of information to the press to gently introduce the fact that Jaguar had two competing supercars.

Writing the book was a most interesting experience, and I was pleased that I remembered so much. “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there…” The famous first line in LP Hartley’s The Go-Between captures the problems encountered by memory and history that often produce conflicting results. I was also pleased that a lot of it was fun to recall and write.

I was also pleased that a lot of it was fun to recall and write. A designer will always be a designer, whether evaluating his own work, during the design process or after production has begun. For me, it’s the same with a book. Ask me in a year how I feel about it; it took me 15 years to understand what we had achieved with the McLaren F1.

You can purchase JaguarSport XJR-15 here.