WORDS: WINSTON GOODFELLOW | PHOTOS: AUTHOR

What makes a car worth a million dollars, and more? A key attribute is mystique, and this grouping of Shelby Mustangs is a concise treatise into a potentially murky subject.

At the centre of their tale is a character straight out of central casting – to which we can now say ‘literally’. Carroll Shelby’s run from 1959 to 1969 may be the best ten years by anyone in automotive history, for he went from Le Mans winner with Aston Martin in June 1959, to a washed-up and nearly broke racing driver on October 24, 1960. Within two years of a heart condition forcing his retirement, he achieved his long-held ambition of becoming a sports car constructor, and within two years of that his Cobras had won multiple SCCA and USRRC championships in America.

In the following 24 months, his Cobra Daytona Coupes defeated Ferrari for the FIA endurance-racing crown, and in 1966 he became the only individual to win Le Mans as a racer, team owner and constructor, when a Shelby American-prepped GT40 took the chequered flag. In between were other projects such as the King Cobra, 427 Cobra and Sunbeam Tiger – all this engineering and creating taking place under sun-kissed skies not far from southern California’s mythical Pacific coastline.

When the difference between cars and how they feel vanishes, will such mystique survive? Or will it become even more revered?

Such accomplishments form an impressive heritage, but what separates Carroll and Shelby American’s legacy from that of numerous other great marques is approachability. To wit: if the nameplate had only produced approximately 990 Cobras, the six Daytona Coupes that won 1965’s World Championship, and the GT40s that twice won Le Mans while dominating endurance racing from 1965 to 1967, it would be as highbrow and untouchable as the revered names from Italy, the UK and elsewhere.

But in the second half of 1964, Carroll’s special ‘pixie dust’ found its way into something most anyone could buy. That’s when Ford vice president Lee Iacocca called to see if Shelby could turn the recently released – and selling like hotcakes – Mustang into a sports car. “It was a secretary’s car that sold for $2395 and had a three-speed transmission,” Carroll told me. “I said to Lee: ‘I don’t think that’s a very good idea.’

“Iacocca said: ‘I didn’t ask you that.’”

Several Mustangs were sent Carroll’s way, and he and his men took that ‘secretary’s car’, applied said pixie dust, and created the GT350 “that is all that most of us wanted the original Mustang to be in the first place,” as Car Life’s road test concluded. More remarkably, its competition sibling was victorious in its first-ever race, and the GT350R won a number of championships over the next several years besting Corvettes, Alfa Romeos, Porsches, Jaguars and more.

By the summer of ’66 the letters ‘GT’ were part of the motoring public’s lexicon, and Ford’s management tapped the phenomenon with its second-generation, restyled and more refined Mustang. For Carroll, that meant: “The Mustang got bigger and heavier. I couldn’t build a race car out of it; I couldn’t build a sports car out of it, so we had to have a bigger engine.” For 1967 Shelby debuted the 428-powered GT500, and sales soared 50 percent-plus over 1966’s totals to top 3000 cars. Then Carroll’s landlord called, unexpectedly terminating the company’s lease.

A mad scramble ensued, and production moved to Ionia, outside of Detroit. Although purists feel Shelby lost its southern California mojo from the move, what they tend to overlook is that the unquenchable desire to create hotter-performing cars never left Carroll, and his key personnel. Experimentation continued apace, and in 1968 Shelby’s muscular GT theme advanced when the GT500KR became available with a more powerful 428 Cobra Jet V8, extra bracing, different exhaust and, on four-speed KRs, staggered shocks.

In 1969 the GT350 and GT500 gained new bodywork that was vastly different from all other Mustangs, but with the Mach 1, Boss 302 and Boss 429 also in Ford dealerships, the end was approaching. In February 1970, with no fanfare whatsoever, Shelby and Ford parted ways, and over the next several years Shelby Mustangs were simply used cars, continually depreciating so most anyone with desire and a little spare change could acquire one. Indeed, back in the mid-1970s 1965-66 GT350s could be purchased for less than $1500.

Which is when the first oil crisis hit, and enthusiasts wondered whether they would ever see engaging performance cars again. Interest in Shelby Mustangs started to blossom, and a mystique that surrounds something special was becoming recognised. This was especially true in the mid-late 1970s malaise of interesting, new automotive offerings.

That awakening raises a question: What causes such mystique to originally form?

In what may seem a blasphemous comparison on first glance, we can identify many of the elements by examining the Modena area and its famed constructors, and comparing them with Shelby and these Mustangs. We’ll start with a broad picture; both central Italy and southern California have long-standing cultures of speed stretching back into the 1920s. In Modena, testing was done on the street, competitions were held at circuits in town and later, the Aerautodromo di Modena; in southern California, the dry lakes and local circle tracks were the proving grounds. Following World War Two, both locations saw a large influx of engineers and craftsmen looking for places to apply their skills, and word quickly got out that speed shops and specialist manufacturers were hiring.

Some constructors’ reputations would become lofty enough to spread around the world, and over the years people flocked across multiple time zones to work for them. For instance, Bob Wallace left New Zealand and would spend time at Ferrari and Lamborghini; several years later Phil Henny travelled from Switzerland to southern California to work for Carroll. When each left their home country, neither spoke the tongue of the land to which they migrated.

For locals the process was far easier, some arriving at factories in cars that inadvertently became ‘resumes’. In 1957 Giotto Bizzarrini was interviewed at Ferrari, travelling in his modified Fiat Topolino that was his graduating thesis from college. The engineer later told me it was Ferrari’s seeing the car that got him hired. Some seven years after that, southern Californian hot rodder Bernie Kretzschmar drove to Shelby to apply for a job. He pointed out that not one person reviewed his application; instead, they crawled over and under his ’32 Roadster that had appeared on the cover of Rod & Custom. He, too, got a job.

Luring them were the charismatic characters behind the companies. Shelby, Lamborghini, Ferrari… employees would walk through fire for these larger-than-life figures to be part of the special atmosphere they and their organisations created. Racer John Morton told me about foregoing evening activities to head back to the Shelby factory: “I would return after dinner, because those employees that were of any value… had something going on they had to get finished, and I would come back just to watch them.” That sounds much like what former Lamborghini chief engineer Giampaolo Dallara said about working on the Miura and 350GT: “We were there all the time. It was so exciting, and happily we did not realise how difficult it was.”

These ‘individuals of value’ were people such as Maserati’s chief engineer Giulio Alfieri, who could “create something from nothing” according to Dallara. At Shelby the magician was Phil Remington, whose uncanny ability to devise a solution to most any problem meant he usually solved it the first time he tackled it.

Another component to mystique is the test drivers – memorable men with an innate feel for how to make a car better. Guerino Bertocchi at Maserati, Bob Wallace with Lamborghini, and Giotto Bizzarrini at Ferrari, Iso and elsewhere were masters at developing and refining road models and/or competition cars. In southern California, Ken Miles helped transform Shelby’s Cobra, Daytona Coupes, GT40s and GT350s into world-beaters, and in 1966 he would one-up his Italian counterparts by winning Daytona, Sebring and, realistically, Le Mans.

This brings us to the machinery these individuals made and, specifically, the Mustangs seen here. The creators injected their DNA into each, and whether the cars were built by Shelby or the competition, basically all had the same mission; to go faster than whatever was next to you.

Carroll’s organisation may have utilised mass-production parts more than his Italian counterparts, but the results were the same. Race winners emanated from their respective factories, numerous new components were designed and/or machined in house, and that formed an ethos to create seriously engaging road cars. The 1965 and ’66 GT350s are charismatic performers, enthralling driver and passenger alike with nimble handling, superior cornering and braking, and a solid-lifter engine that loves to rev while sounding like music.

At the time of our photoshoot, these Shelbys were part of auction impresario Craig Jackson’s collection; the GT350 coupe is one of 521 made in 1965, and was a single-family-owned, 19,000-mile example that sat untouched for 30-plus years. “I never had a streetcar from 1965,” diehard gearhead Jackson reflects. After the car’s purchase: “An idea came up; could we restore (it) to go win all the awards, which we did… At the Mustang Club of America it won the Thoroughbred Class and the Authenticity Award, which means it has to have 99 percent of the parts it came with on the assembly line.”

While Craig jokes that the difference between production-line and NOS parts is their price, because the ’65 had so much assembly-line ‘unobtanium’ on it, shortly after our shoot he said: “It’s the only car in my Shelby collection I don’t drive. I want to take it out and smoke the tyres.” Not trusting himself to have such restraint, he decided to part with it – and at Barrett-Jackson’s March 2021 sale, it brought a world-record $962,500.

The ’Stang group highlights another element of mystique: rarity. One-offs, hand-built prototypes, experimentation and eye-catching coachwork were Italian hallmarks in the decades after the war. Shelby, too, had its share of such machinery, and also made what in Italy were called fuoriserie cars – which is where the GT350 convertible comes in. Ferrari and coachbuilder Sergio Scaglietti constructed 10 NART Spyders in 1967-68; Shelby built four GT350 convertibles in ’66.

Powering them was a 306bhp 4.7-litre V8, and all were individually specced with different colours and options. Craig’s is one of two four-speed cars, the only one in red, and it’s the Shelby he uses the most. “After I bought it,” he says, “we got all the bugs out. The clutch was chattering away, and the cam had flattened out. It’s restored, but not to the degree of the ’65, and it’s a lot of fun to drive.” He often uses it to commute to work, and it’s the one I most wanted to try, but threatening rain and the need to complete our shoot before the heavens opened up didn’t allow that. About its value, its ’66 green convertible counterpart with an automatic transmission sold last year at auction for $1.1million; this is very likely somewhere north of that.

While a run of just four definitely makes something rare, one-offs may be the most coveted road cars of all. In the 1950s and ’60s Ferrari had a number of models that were peppered with one-offs during their production runs, and Maserati did the same with its A6G2000, 3500GT and 5000GT. In the 1960s, Shelby built the GT500 Super Snake, Green Hornet and Little Red, all one-offs with ‘take no prisoner’ attitudes. The latter two are seen here – and Little Red introduces another element of mystique: urban legends.

In August 1966, Shelby ordered three early big-block Mustangs to start the GT500 development process: a convertible, a fastback that would become the production template, and a notchback. The last of these became known as Little Red – a name given to it by Shelby’s chief engineer Fred Goodell, who used it regularly.

“When it arrived at Shelby American in southern California,” Craig notes, “it became their test bed for engineering innovation.” Changes were numerous, and constant. Jackson’s in-depth research indicates that it came with a 428ci V8 powerplant fitted with two four-barrels; at some point it likely had Lucas mechanical fuel injection, plus it had single and double superchargers (the latter registering 600bhp on the dyno). The three-speed automatic transmission got an experimental tail-shaft, there were special rear brakes and a massaged exhaust system, while the cosmetics saw numerous changes as different ideas were tried.

To comprehend Little Red’s reputation, Charles Fox’s column in Car & Driver’s April 1978 issue recounts a drizzly southern California evening spent behind the wheel. “It was as quick as the Vicar’s daughter to a hundred,” he noted, “but the real magic came between a hundred and when the nose started to get airborne (at) 135-140mph. It was annoying having to lift with 1500rpm in hand.” Eye-opening stuff for the era –and even more eye opening was his ending up in jail for exhibiting such speed…

According to the 1965-1967 Shelby Mustang Registry, Fourth Edition, after three years of tearing up southern California and Michigan’s asphalt: “Little Red was sent to Kar Kraft in Brighton, Michigan sometime in 1970, and unceremoniously crushed.” For decades, that’s what Shelby historians and the Mustang world believed, so when noted restorer Jason Billups suggested to Jackson and crew: “What about Little Red?” they rolled their eyes at the thought it might still be out there, somewhere. As Shelby American’s marketing manager Scott Black noted: “You cannot find what cannot be found.”

On a whim, Billups gave the Ford (rather than the Shelby) chassis number to a private detective, and to his great surprise they got a hit from a 1994 registration. Billups ended up tracking the owner down, and Jackson would eventually purchase the dilapidated car out of a field in Texas. (The story is superbly recounted in the video The Hunt for Little Red.)

Because so little was actually known about Little Red and its history, Jackson made an intriguing decision; to create and publicise a website to crowdsource the real story. With new information flowing in from multiple ex-Shelby and Ford employees and their family members, he says: “Restoring this car was an archaeological dig. Going through with everybody… who had anything to do with it… The car spoke to us when we took it apart, for it had many 1968 prototype parts on it.”

Crucially, they found Walter Nelson, the individual who originally built Little Red for Carroll, and the only known period colour photograph he possessed. Today Little Red has been meticulously restored to what Jackson calls “its biggest, baddest self”, complete with twin blowers that, amusingly for a Shelby, look like cobras slithering across its big V8.

The Green Hornet is also a one-off test bed, built in 1968, and it too has undergone a painstaking restoration. “It’s amazing how similar the two are,” Jackson says, “just different technologies. One is brute force, the other high tech – reflections of the different mentalities of southern California hot rodders and Detroit.”

‘GT350s are charismatic performers, with nimble handling, superior cornering and braking, and a solid-lifter engine that sounds like music

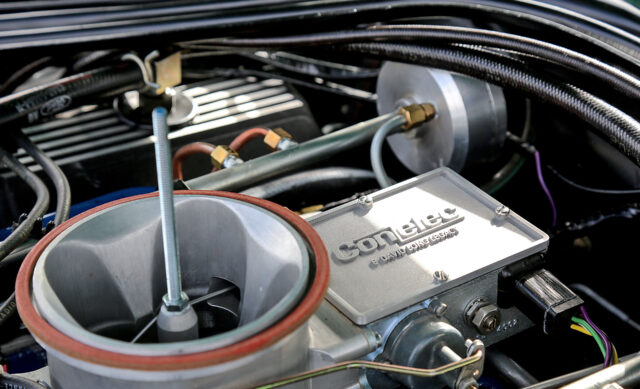

No superchargers are found in the Hornet’s engine bay; instead, there’s a Conelec fuel-injection system augmented by what was likely the world’s first automotive computer. The modified 428 V8 makes 500bhp on the dyno, and unlike Little Red and every other vintage Mustang, the Hornet has an independent rear suspension set-up.

Had Shelby put the car in production, the 2+2 coupe would have played havoc with the competition. At Ford’s Michigan proving grounds, the Hornet hit 0-60mph in 5.7 seconds, 100mph in 11.4, and averaged 157mph over four laps. For comparison, a Vantage-spec Aston Martin DB6 and Ferrari 365 2+2 needed 6.1 and 7.8 seconds to 60mph, 15 and 20.8 seconds to 100mph, and topped out at 148mph and 152mph, respectively.

Which leads into perhaps the most important element of mystique: how something drives. Over the years, I’ve spent time with the Aston Martin, Ferrari, Green Hornet and other 2+2 competitors such as Lamborghini’s Islero, Iso’s Rivolta GT and more. All deliver entirely different experiences behind the wheel, so they feel like nothing else. The same can be said for the 1965 and ’66 GT350s, which ‘taste’ somewhat like Ferrari’s 250 SWB in terms of sensations and noises while maintaining their own distinctive characters.

But these are machines from a different era, one that lasted for decades. Now there is an unrelenting proliferation of electric vehicles, and the eventual disappearance of brand-new internal-combustion cars seems inevitable. Manufacturers continue to engineer out noise, vibration and harshness – those minute characteristics that give automobiles true individuality on the road – all while speaking of achieving Levels 4 and 5 autonomy. When the difference between cars and how they feel completely vanishes, will such mystique survive? Or will it gain additional significance, and become even more revered?