Words: David Lillywhite | Photography: American Speed Festival

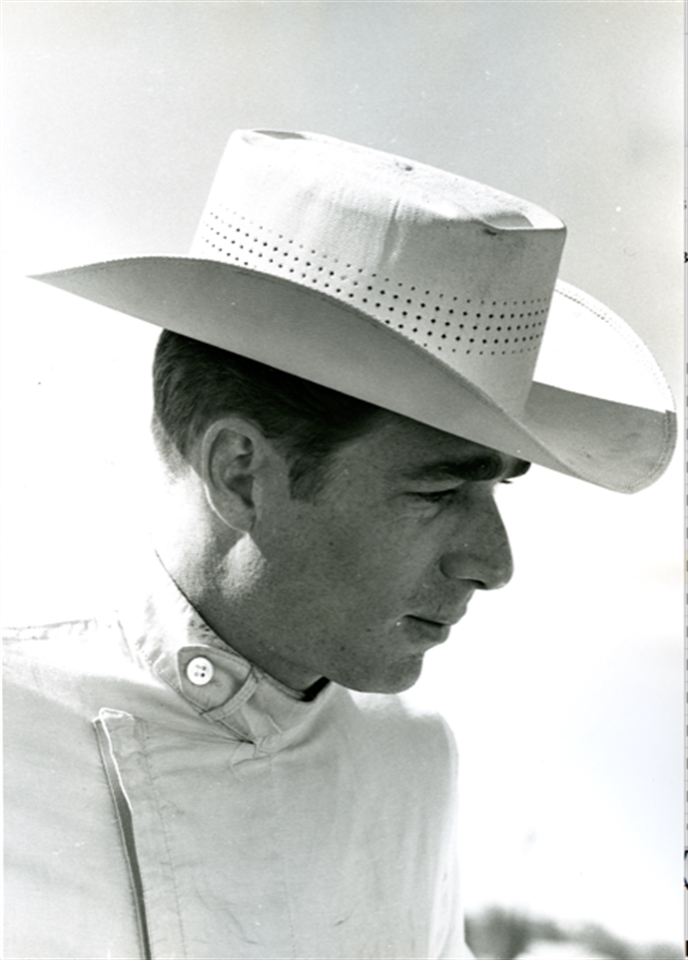

Jim Hall revolutionised motor sport in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, creating cars for Sports Cars, CanAm and Indy that not only changed the face of racing at the time, but which have influenced competition-car design ever since.

Now 86, Hall still owns his Chapparal race cars, which are displayed at the Petroleum Museum in Midland, Texas. Although unable to visit in person due to Covid concerns, he’s loaned four of them to show at the inaugural American Speed Festival at M1 Concourse, Detroit, from September 30 to October 3, 2021.

We talked with Jim at his home, where he explained how he came to use his childhood fascination with cars and his mechanical engineering degree to become one of the most innovative, aerodynamic-savvy race-car designers of all time.

“You know, I don’t remember a whole lot about my childhood. I know I got in trouble like everybody else, but I always wanted to know how everything worked – and that was a real challenge to me to find out, well, how does this work or why does that do that? I think that my curiosity about the physical world around me is probably what made me a little different.

“In racing, I think I had the advantage of sitting in the seat, and feeling the changes and then going back and writing the equations form. I just happened to come along in a good time with the right education.”

There are often comparisons made between Jim Hall and Colin Chapman, but we wondered what Hall himself thought of his British rival. “Well, I tell you I admired him a lot,” says Hall. “I had two cars that really inspired me early in my career. One of them was the Mercedes 300SL. I looked at it and I realised they went to a lot of trouble to get a stiff chassis, and keep it torsionally rigid and do the things you would do that I thought were important for handling, and so I really admired that car.

“And then, I think, Colin’s Lotus 11 was the first car I looked at and thought ‘man that car is shaped right’. You know it’s shaped like it needs to be; it’s got high doors, you can put a stiff frame under it. It’s just really good-looking, and I thought the engineering in that car was quite forward thinking for that period.

“I admired his [Chapman’s] work a lot. For some reason, I think he tended to build stuff a little bit light. But, you know that’s what you’re trying to do, you got to make a compromise there somewhere, ensuring it’s going to make it through the race.”

The first Chaparral race cars were built by Dick Troutman and Tom Barnes. Jim Hall and Hap Sharp bought two of them to race, and when they began building their own cars they asked Troutman and Barnes if they could use the Chaparral name.

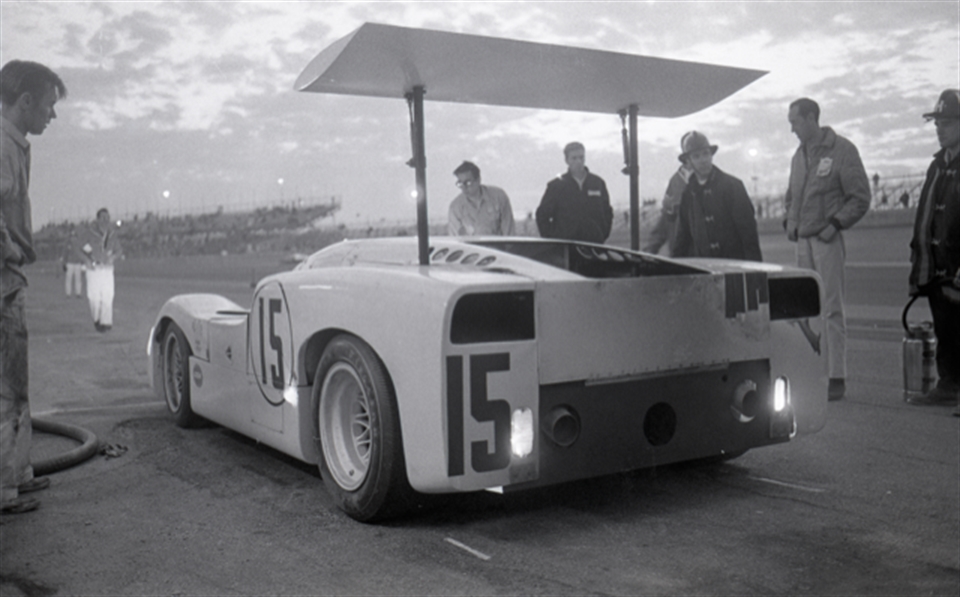

Hall and Sharp’s cars were subsequently all named Chaparral 2s, developing through 2A to 2J for the sports and CanAm cars, and 2K for the 1979-1982 IndyCar (despite winning the Indianapolis 500 in 1980, they left racing in 1982). There was innovation from the start, with extensive use of glassfibre plus a three-speed automatic transmission hooked up to the Chevrolet V8 engine.

New versions followed fast, with the 2C featuring a high rear wing that could be adjusted via a foot pedal in the cockpit (possible because there was no clutch thanks to the auto transmission). It showed great promise, but it was outlawed before long.

Was Jim surprised when it was banned? “Oh, it took us a little by surprise; I felt like those cars were really quite nice to work on and drive because there were so many good adjustments you could make easily. You could tune the car for almost any racetrack and make it feel good for the driver.

“I always thought that was an important feature. It should be not too hard physically, and it should also give you the confidence of where the car is going to be on the race track. So I was disappointed in that, and I didn’t see why we should not be able to do that.”

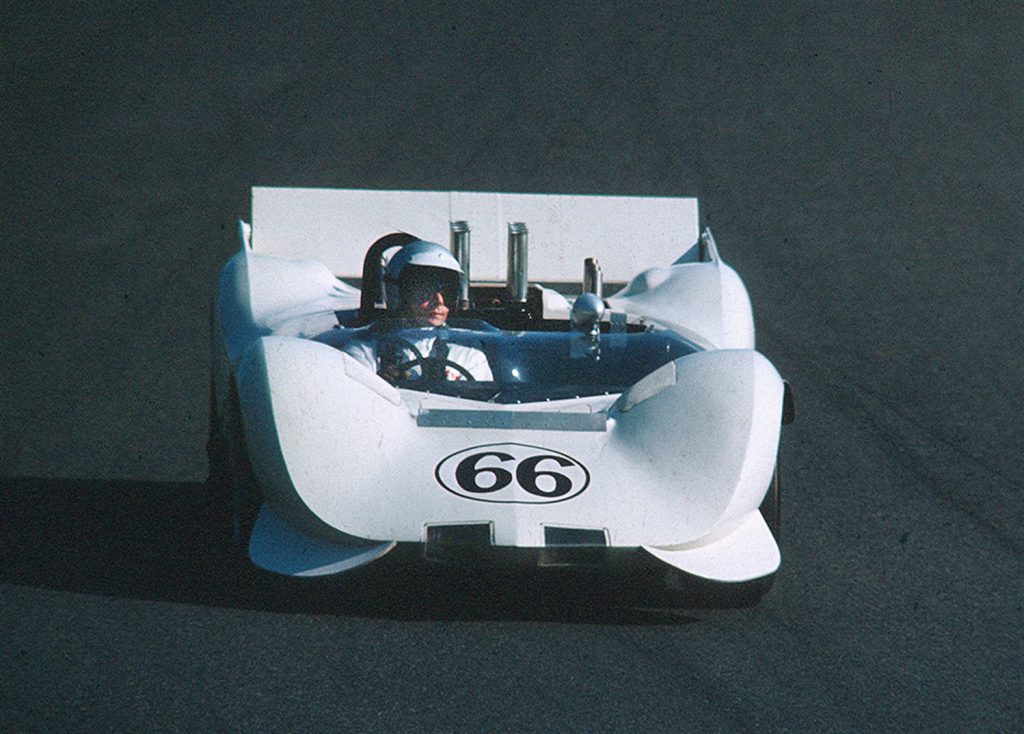

For the 1970 CanAm season, Jim Hall introduced the 2J, which used a small two-stroke engine to run two large fans at the rear of the car to suck it to the track, helped by plastic skirts around the lower bodywork. Once again, it was banned.

“I was not surprised [by the ban] on the suction car, but I thought that at least they would give me a year,” says Jim. “You know, I thought, if you spend all this time and effort, and you bring something exciting to the racetrack. People want to see it run and we want to run it, make it successful.

“We never did really make that car successful, either, but it was so fast it scared everybody and it probably had to be regulated in some way because otherwise it would have made the tracks not be able to handle the cars at that speed. So, I agree that should have happened there, but I thought maybe they’ll give me a year to run the thing, and I was disappointed they didn’t.”

The notoriety makes these the best known of the Chaparrals, but there were many more, in varying styles, open and closed cockpit, with both glassfibre and aluminium bodies. Which is Jim’s favourite, looking back?

“I think probably the 2E. You know, we started with a brand-new sheet of paper, and we decided to put in everything we knew about aerodynamics at that time into that car. It was a major change in how the aerodynamics was handled on race cars. I think it showed everybody that was a major factor in car design at this point.

“Not everybody believed that at the time, but I think after they saw the car they realised that aerodynamics was a very important feature. A lot of aerodynamic work was done before, but generally it was done on the stability and drag; nobody really focused on download.

“When I realised the effect of download on the car in late 1963, I realised what a huge benefit it would be to control the download, and monitor it and make it work for you, instead of having it work against you. I think that was my major discovery during my life.”

While CanAm provided a perfect playground for Jim’s innovation, it’s remarkable that at the same time Chaparral was starting out, Jim was also involved in Formula 1 as a driver for the British Racing Partnership. This at a time when the championship was starting to go through fascinating changes – not unlike it is today.

“Yeah, it was much different when I was in Formula 1. It was probably like the smaller club racing is today. For instance, in our team [BRP] we had two drivers, two mechanics and two helpers. And that’s kind of the way it worked. We did rely on the engine supplier to overhaul the engines and send them back, so the teams didn’t do that, but they maintained the cars, and whatever development we had during the season was quite small.

“One of the most exciting races for me to go to was Monte Carlo. When we went there, we got to practice between 4:00 and 5:30 in the morning, and then they cleared the streets for traffic. So, you know our practice sessions were a little different from the way they do it today.”

Now, Jim Hall has been inducted into the Motorsports Hall of Fame at M1 Concourse, and his son and grandson will demonstrate the Chaparrals on track at the American Speed Festival. How important is it to Jim that the cars are shown in public like this?

“It’s always a thrill to me,” he says. “I think a lot of my real good feelings come from the youngsters who have read about it [Chaparral] but who obviously didn’t see it [at the time]. They’re still excited about it, and I get more fan mail from young folks in Europe than I do from the US.

“I felt like my education, which I worked hard for, really helped me in life, and I want to share that with the younger folks. I know studying math isn’t any fun. But boy, there’s some stuff you can do with it and there’s physics that you could really enjoy. I sure did! So that’s one of my real happy moments in life, when I hear from some young fella who enjoyed finding out about our cars.

“My son and grandson know how to drive the cars – they’ve driven them before, and so it’s an honour for me to have both go up to the American Speed Festival and show the cars.”

A book on Jim Hall’s achievements, written by Motorsports Hall of Fame president George Levy, is about to be released. The Chaparral 2 (USRRC winning car), the 2E (CanAm), the 2F (World Sports Car series) and the 2K (IndyCar) will be demonstrated and displayed at the American Speed Festival on September 30-October 3.

If you liked this, then why not subscribe to Magneto magazine today?