Ferrari has achieved back-to-back victories at the Le Mans 24 Hours, after 499P no. 50 took the chequered flag 14.2 seconds ahead of the no. 7 Toyota GR010 Hybrid in a nail-biting finish at the 2024 staging of the legendary endurance race. Ferrari’s second triumph comes only one year after the brand dramatically returned to Le Mans in 2023, following a 50-year hiatus, when it beat the likes of Porsche, Toyota and Cadillac on the first time of asking.

Despite Ferrari’s long hiatus from competing at La Sarthe, it is one of the race’s most successful manufacturers, with a grand total of 11 overall victories to its name. Only Porsche and Audi sit above Ferrari on the all-time list, with 19 and 13 wins respectively.

That 14.2-second gap from the winning Ferrari to the no. 7 Toyota is the narrowest winning margin seen since 2011. Ferrari’s winning trio of Antonio Fuoco, Miguel Molina and Nicklas Nielsen completed only 311 laps on their way to victory, with treacherous conditions creating four hours’ worth of safety car running through the night.

Coming home in third place was the sister no. 50 Ferrari of Alessandro Pier Guidi, Antonio Giovinazzi and James Calado, who claimed the win in 2023.

To celebrate Ferrari’s historic second successive victory, we look back at the La Sarthe moments that wove the brand’s storied status, as written about by Richard Heseltine in Magneto issue 11’s Top 50 Le Mans 24 Hours Moments feature.

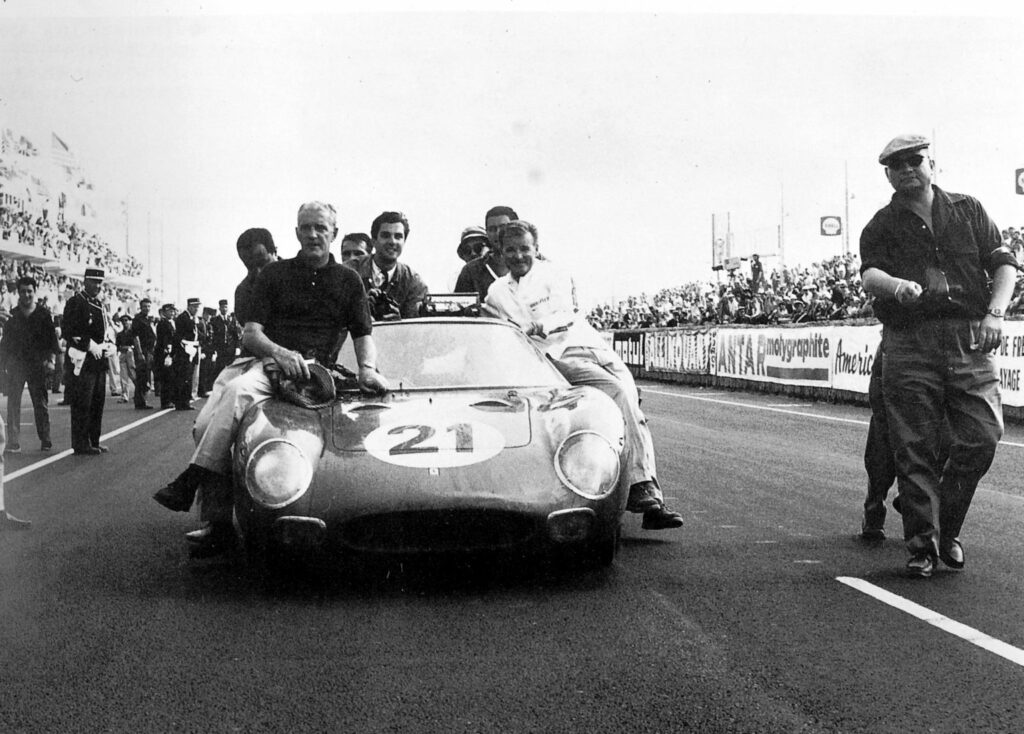

The Third Man, 1965

Oh, where to start? The 1965 Le Mans 24 Hour race has long since passed into legend. It’s a story of how a privateer squad upheld Ferrari’s honour while the Works team fell apart, and Ford’s mega-money bid floundered. Even then, victory was only secured late in the day. The thing is, this is only the amuse-bouche to the big story; that a third, uncredited, driver got behind the wheel of the winning car for a stint. And then there are the reasons why he was installed in it in the first place.

Predictably, the GT40 army led the charge come 4:00pm on June 19 of that year. It didn’t last long. Ferraris blanked the top six positions as darkness fell. By the early hours of Sunday morning, the 250LM entered by Luigi Chinetti’s NART squad, and shared by Jochen Rindt and Masten Gregory, was lying in a distant third place. By midday, just 14 of the 51 starters were still lapping, with the Franco-Belgian partnership of Pierre Dumay and Gustave Gosselin seemingly on target to take the win aboard their 250LM.

However, Rindt was lapping faster than Dumay in the NART 250LM that was now in second place. And then the leader’s luck took a tumble late in the day; Dumay somehow managed to control his car after it developed a puncture while travelling flat-chat down the Mulsanne Straight. Five laps were lost making repairs. There was no way the deficit could be clawed back, so Rindt and Gregory came home the victors, Chinetti adding a win as an entrant to the three he had accrued as a driver. That would be a great story in itself, but the narrative surrounding how the race was won has since taken on a credibility-stretching life of its own.

These days, reliability tends to be of the bulletproof variety. Way back when, cars tended to be nursed, coaxed and cajoled into completing the distance – and the 250LM’s transmission was notoriously fragile. Some state as gospel that Rindt and Gregory fully expected their car to retire early, so deliberately beat on it. Why flog your guts out and prolong the inevitable? Somehow, though, it stayed together. Asked about this, Luigi Chinetti Jr, who was on site that year, said: “If dad thought for a moment that they were trying to break his car, he would have broken their asses.”

Additional intrigue surrounds claims made by NART regular Ed Hugus that he had picked up the slack during the night; that Gregory didn’t enjoy driving in the dark because he wore glasses, so Hugus took his place. His involvement was purportedly glossed over because it would have led to the car’s disqualification. His version of history has, astoundingly, been accepted as gospel truth in certain circles – and in print, too.

However, there isn’t an iota of a scintilla of a nuisance of evidence to suggest that any of it is true. A lack of proof doesn’t mean something didn’t happen, of course – but without corroboration, you have to doubt the veracity of Hugus’s claim.

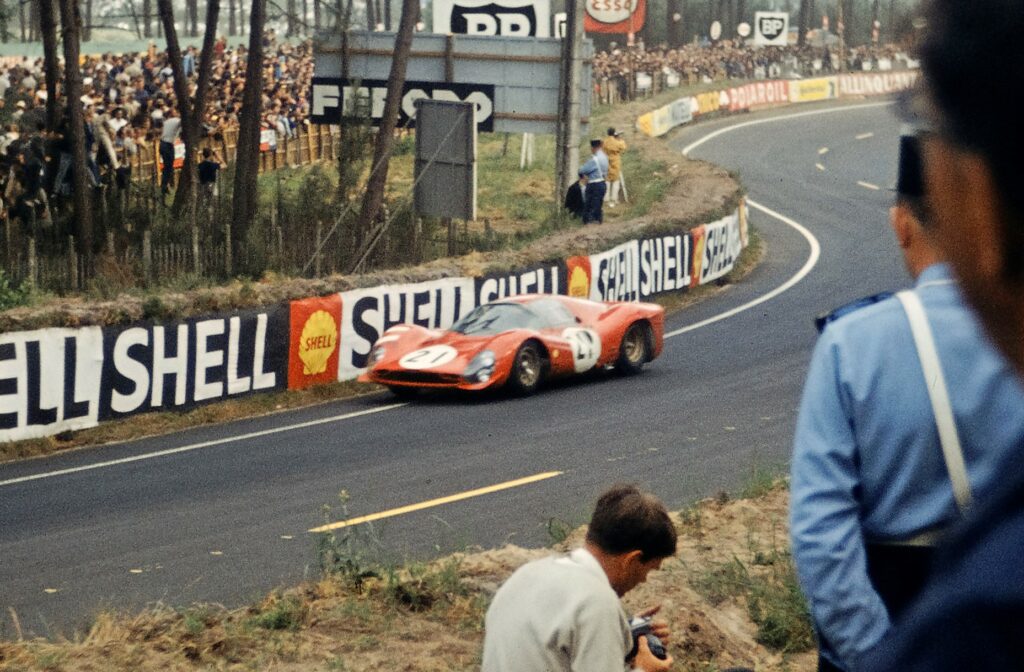

Ford vs Ferrari, 1966

It was a battle for supremacy the likes of which had never been seen before. Henry Ford II, having been jilted at the altar by Enzo Ferrari, vowed revenge. He got it, too. However, the legend behind how the Blue Oval bested the Old Man is precisely that. It has been embellished beyond recognition in print, and reimagined by Hollywood to the point that it’s hard to differentiate the actual from the apocryphal. What is undoubtedly true is that victory for the Ford GT40 wasn’t the work of a moment.

Ford’s budget for its Le Mans bids, let alone the Total Performance programme as a whole, was astronomical. One insider likened it to that of the Moon Landing. Nevertheless, the first attempt at the 24 Hours in 1964 ended with retirement for all three cars. A year later, it was another washout. Then, in 1966, the 7.0-litre Mk2 scorched to victory with a staged close-formation 1-2-3 finish. It marked the end of Ferrari’s run at Le Mans, the Italian marque having won year after year since 1960. However, it is worth pointing out that Ferrari did sports cars, Formula 1 and various other disciplines, spending the sort of lira that wouldn’t cover Ford’s catering budget.

It is also worth recalling that while Ferrari got its bottom kicked on hallowed ground in 1966, it did return the favour at Daytona the following year. It finished 1-2-3 – but we have yet to see a film about that… Joking aside, though, there is no denying the fact that Ford set itself a goal and achieved it. And how. The 1967 Le Mans race saw AJ Foyt and Dan Gurney win in the mighty Mk4, while JW Automotive/Gulf squad famously claimed honours in 1968-69 using the same GT40 (no. 1075). ‘The Deuce’ got his revenge on Il Commendatore. We should all be grateful that Enzo got his back up in the first place.

Bull Fights Jaguar, 1954

Jaguar had claimed a resounding win at Le Mans in 1953. The highest-placed Ferrari was down in fifth spot. A year later the Scuderia returned with three 4.5-litre 340 (375 Plus) sports racers. Jaguar, by contrast, had a new weapon in its armoury; the D-type. And that’s before you factor in other works and privateer squads. Of the 57 cars that made the start, only nine were classified, but the Ferrari-Jaguar battle raged to the end.

By dawn, just one factory Ferrari and a lone D-type were still running. The Jaguar was helmed by the previous year’s winners, Duncan Hamilton and Tony Rolt; the scarlet car by Maurice Trintignant and José Froilán González. The latter pairing appeared comfortable until the heavens opened again, with two hours to go. The Jaguar started making inroads; even more so after the sodden Ferrari pitted for the final time and took an age to fire again. Hamilton charged in a manner he later deemed almost suicidal, but the ‘Pampas Bull’ responded in kind. Nevertheless, they were just 87 seconds apart as the chequered flag descended.

Ferrari’s Maiden Win, 1949

The fledgling Ferrari marque claimed its maiden win in 1949, this being the first year the 24 Hours had been staged in peacetime. And it fell to long-time Ferrari ally Luigi Chinetti to make it happen. Already a double victor, having claimed honours in 1932 and ’34 aboard Alfa Romeos, the racer/concessionaire was paired with Peter Mitchell-Thomson (Lord Selsdon) in the latter’s 166MM. However, the British blueblood was a team-mate in only the most nominal sense.

Chinetti, who was 47 years old at the time, did the bulk of the driving. And how. According to Motor Sport magazine’s race report, Selsdon didn’t take the wheel until 4:26am, by which time his 2.0-litre barchetta was comfortably in the lead. He reputedly felt unwell and relinquished it again at 5:38am. There were weird parallels with the 1932 race, where Raymond Sommer did the bulk of the driving en route to victory after Chinetti was stricken with a fever. Here, he battled fatigue, a slipping clutch and a lot more besides to become the first three-time winner.

Mexican’s Rave, 1961

That Ferrari scorched to victory in 1961’s 24 Hours surprised nobody. Eleven cars featured among the 55-strong entry, the works team having set tongues wagging during the April test weekend when Richie Ginther’s V6 Dino 246 SP lapped three seconds faster than second-place Phil Hill’s 250 Testa Rossa. Pedro and Ricardo Rodríguez in the privateer NART 250 TRI/61 stole the actual race.

By 11:00pm, the supremely fast Mexicans were dicing with the works Ferraris on a drying track. On the Sunday morning, they lost nearly 30 minutes due to a misfire, but soon recovered. However, with two hours to go, their engine let go at Maison Blanche. They’d been running in second place and were in contention for victory. Their retirement gave Olivier Gendebien/Hill breathing room, and they recorded Ferrari’s fifth win to equal Bentley and Jaguar’s record.