WORDS: MASSIMO DELBO, JAMES NICHOLLS | PHOTOS: BMW, LAMBORGHINI

Reserved and softly spoken, Marcello Gandini – who has died at the age of 85 – was a Piedmont gentleman. More than that, though, he was a creative genius. Indeed, the ‘Gandini wedge shape’ became nothing less than the automobile style of the 1970s.

Marcello grew up in Turin, with a musician father who hoped his son would follow in his path. But Gandini’s life was shaped by a box of Meccano, received as a gift when he was just five years old. After that, his passion for mechanical construction prevailed – and he was proud of how he was able to use his hands away from the drawing board, too, something he often proved by helping out on car models as they were being made.

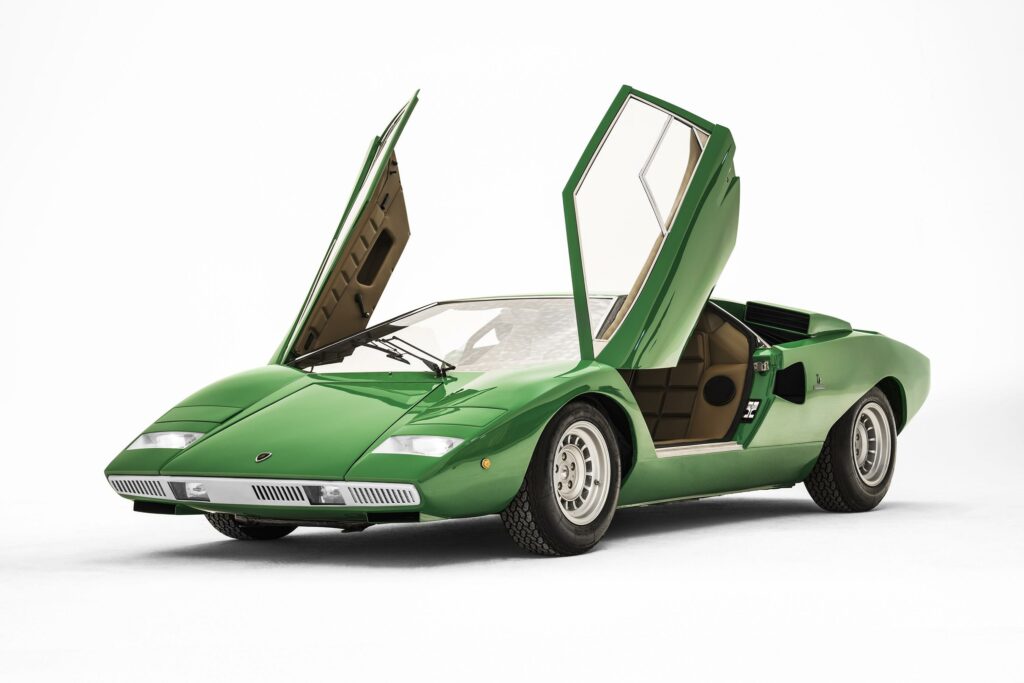

Gandini was hired to manage styling at Carrozzeria Bertone in 1965. He became famous very early on in his career for his seminal work on series cars such as the Lamborghini Miura (1966), Espada (1968), Countach (1971) and Diablo (1989), as well as the Alfa Romeo Montreal (1967), Lancia Stratos (1973) and Ferrari Dino 308 GT4 (1975). In addition, some of the most stunning show cars ever conceived, including the Lamborghini Marzal (1967), Alfa Romeo Carabo (1968), Lancia Stratos HF Zero (1970), Ferrari 308 Rainbow (1976) and Autobianchi A112 Bertone Runabout (1969), all flowed from his pencil.

Stunning show cars, including the Lamborghini Marzal, Alfa Romeo Carabo, Lancia Stratos HF Zero, Ferrari 308 Rainbow and Autobianchi A112 Bertone Runabout, all flowed from his pencil

After 14 years with Bertone, Gandini moved on to work freelance, but he always cherished his time at the carrozzeria. “Bertone was something special in my life, and was not supposed to last for so long. Indeed, I always thought I would have lasted six months, no more. And that was a benefit, as I was left free to create, and able to dare more.”

His extreme sports cars got all the headlines but, talking to him, it was clear that his love was for small, utilitarian cars. “It is easy to create a supercar: you have very few limits in terms of budget and fantasy. It is much more difficult to create a normal production car, where budget, reliability and practicality are the fierce enemies against which a stylist has to fight,” he once said. This is why the 1972 Fiat X1/9, BMW Series 5 E12, 1974 Innocenti Mini 90/120, 1982 Citroen BX and 1984 Renault Supercinq were among his favourite creations. Indeed, he had a soft spot for his revolutionary Renault AE Magnum truck of 1982.

Marcello Gandini’s hugely influential and inspirational body of work left an indelible mark on the automotive world – indeed, he was recently honoured at the Politecnico di Torino.

Farewell, Maestro Gandini.

After hearing the sad news about Marcello’s passing, we were reminded of an interview Sydney Harbour Concours of Elegance founder James Nicholls did with him back in Magneto issue 3. You can read it in full below.

How are you, signor Gandini?

Well, I am 80 years old and still working. I am not moving as well as I would like as I have a bad back at the moment, which is slowing me down a little.

How did you start out in automotive design?

I am the son of a composer and orchestra conductor. Since children never want to do what their parents did, they always try to take different roads – I, too… I dedicated myself to cars and design, and this caused my father some grief. When I was four I started playing the piano, and I had to exercise for years all the time at the instrument, but I did not like it at all. So, it’s important for me because of my parents and my memories, but I am not a musician, I am a designer.

Was there a particular designer you really admired?

The designer who made the greatest impression in my life, and I also got to know him later, was Mr Bertoni, who designed the Citroën DS.

What was so special about the Citroën DS for you?

I particularly like the fact that the DS is one of the few cars that has been constructed freely, not at all worrying about marketing, or product placement, no worries about technicians involved – or indeed the costs. As a matter of fact, the DS almost caused Citroën to go bankrupt, because of all the problems the company had to face in the production of this car. But what is exceptional about this model is the fact that, for once, the designer was really able to do exactly what he had in mind without any constraints. That is very important… isn’t it?

Of your own automotive designs, do you have a favourite?

I don’t like to say which is the favourite of my designs. Is it the Miura or the Countach, the Carabo or the Marzal? I don’t even ask myself what I prefer of my old designs, because I don’t like to look back. I always say that my favourite is the next one that I will do, as even at my age I’m still a designer and continually working on various projects.

Do you still enjoy designing cars?

I still do draw cars, but my job has changed a lot in the past 20 years – even a bit more – because now there are loads of stylists, thousands of stylists, all brands have 500 stylists. And I, by choice and also because it was something I had to do, dedicated my research to the most technical part, to design cars with innovations starting from a blank sheet of paper, up to building a prototype able to run. This is what I like doing most – and I hope I will be able to continue for a long time yet.

What else do you design?

Many things. For sure, there is a connection of some sort between cars and architecture, but I like the design of moving things, not of still things. Having said that, I have also designed many houses, but there is a different feeling from a car, an aeroplane, a helicopter, a motorcycle… because movement modifies, it enhances and gives value to the design and the sensations.

So, do you enjoy designing houses as much as you enjoy designing automobiles?

I like houses, especially the beautiful ones. I’ve designed a lot of houses and I really do love them, but as I say, there’s not the same spirit as in a moving piece of architecture. The moving object has a life of its own, whereas a house can only have a life if someone lives in it. It’s different – it’s a different feeling and sensation. The movement of people in a house gives it soul and spirit – without people it’s only an object. But a car has a life of its own.

More in Magneto issue 3: buy it here.