WORDS: JOHN SIMISTER | PHOTOS: ASTON MARTIN

Article taken from Magneto issue 11 (Autumn 2021)

Meet the oldest Aston Martin in the world; the third car thus branded to be built by what was originally the Bamford and Martin company, and the most senior survivor. The year 2021 marks its 100th birthday, but despite its age it is fully functional and fighting fit.

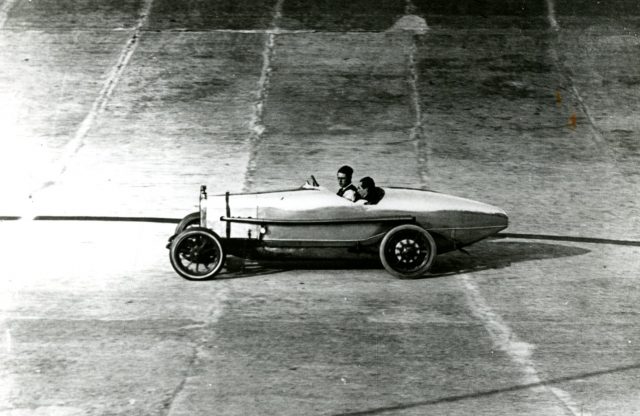

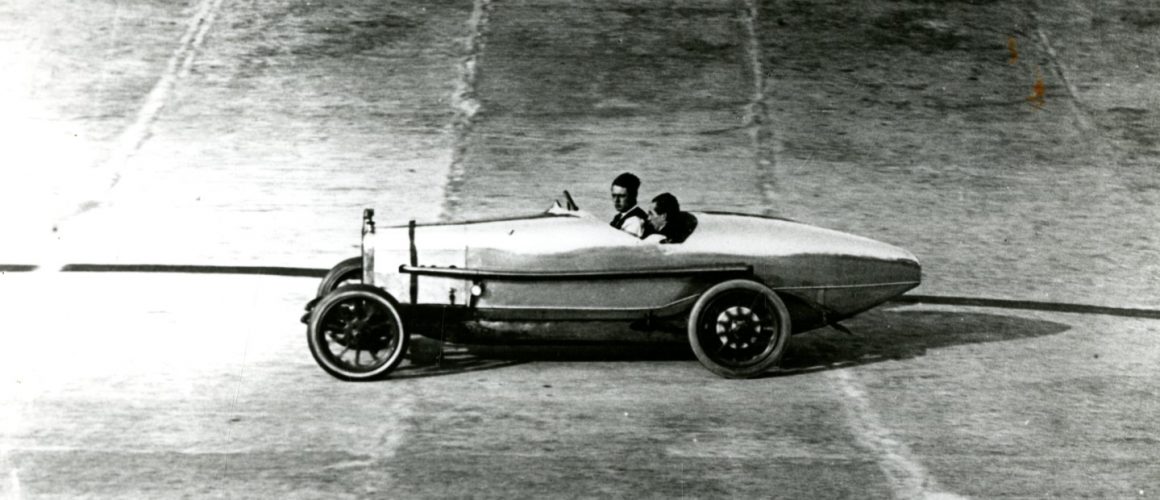

Magneto had the chance to drive chassis no. A3 at Brooklands, where a chunk of its early history was made. Most significantly, driven by Bertie Kensington Moir it took several light-car speed records including 100 miles at an 86.2mph average. That happened in 1921 when A3 was virtually new, meaning that its normal, black-painted bodywork had barely been fitted before it was ousted by a streamlined, long-tailed replacement.

The original look was soon reinstated, but over the years A3 took on other guises. First came a lower, racier one, by which time the factory had renumbered the chassis to 1918 and re-registered the car from AM 270 to XN 2902. Some time later, A3 gained a wire-wheeled, wider-bodied, short-tailed, cycle- winged look redolent of the 1930s (plus, finally, brakes on the front wheels), and its origins faded into history. Not until 2002 did a sharp- eyed expert at the Bonhams auction house spot the A3 marking on the chassis and realise its significance.

The Aston Martin Heritage Trust raised the money to buy A3 a year later, and commissioned a restoration intended to recreate the original as-built look without necessarily honing the mechanicals enough for regular reliable running. Various maladies afflicted the car over the following years, mainly with regard to the gearbox, the differential and, latterly, the engine, but pre-war Aston specialist Ecurie Bertelli has now rendered A3 fully fit at last. When I meet it at Brooklands, the engine is still running in.

Today, A3 looks magnificent with its torpedo-esque bodywork, cast- aluminium artillery-look wheels, ample wood and spindly demeanour. Under the bonnet is a sidevalve, monobloc, four-cylinder engine of 1487cc and maybe 38bhp, fed by a brass SU ‘sloper’ carburettor. Beneath my feet are pedals arranged with the accelerator in the middle; by my right knee is a gearlever whose gate is rotated 180 degrees from normality so the pattern is both back to front and upside down. And no synchromesh, obviously. Not even constant mesh; it’s proper vintage sliding pinions in here.

The A3 starts instantly. It can’t idle for too long because there’s no fan and it gets too hot. It does have a water pump, though; unusual in 1921, when simple convection currents usually did the job. The oil-bath clutch engages smoothly, the throttle feels keen and we are off, soon discovering the optimum double- declutch technique except for fourth, for which crunch-free engagement remains tantalisingly elusive.

The very thought of driving a century-old car might fill one with wonderment, yet in its architecture and the way you make it move A3 is recognisably related to today’s cars. Not in the way you make it stop, though; as part of its reversion to original spec, A3 once again does without front brakes. Pressing hard on the pedal and pulling hard on the handbrake tensions two sets of cables and applies maximum effort to the rear wheels, but that’s no help if the road lacks grip.

This engineering blind spot, found across the motor industry until the mid-1920s, is the only scary aspect to driving this otherwise remarkably capable and usable machine. The oldest Aston in existence lives and breathes, and the final restoration is fabulous. I hope the buyers of today’s Aston Martins appreciate how it all began.