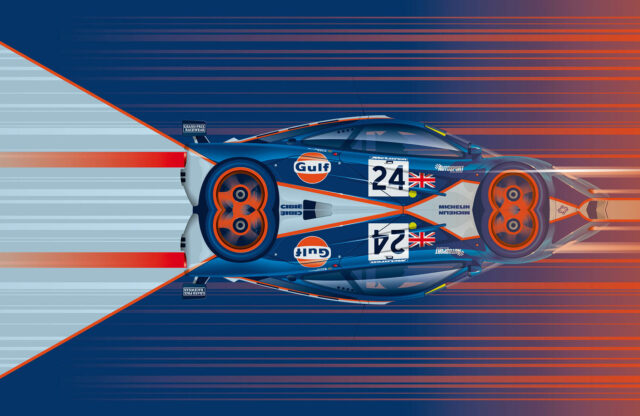

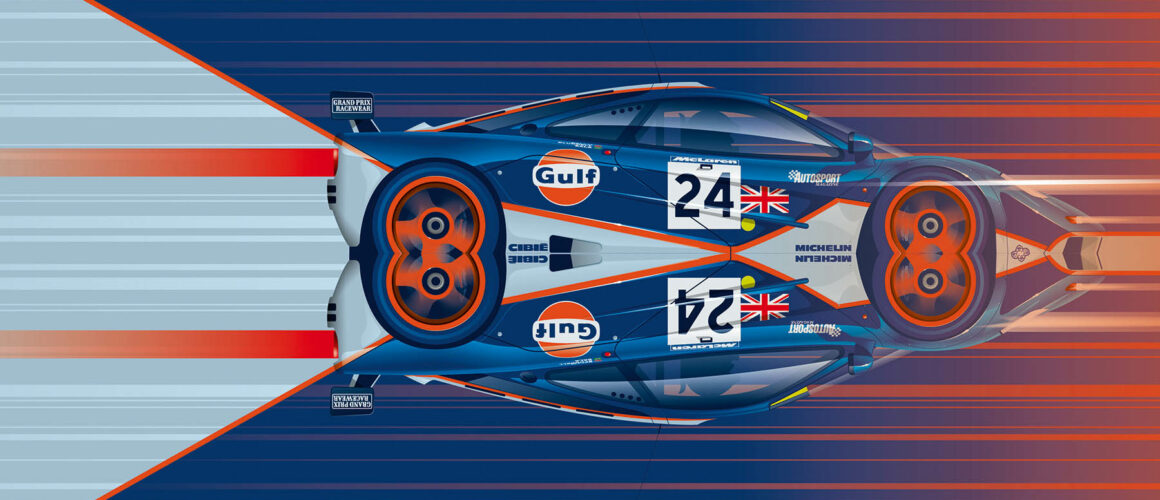

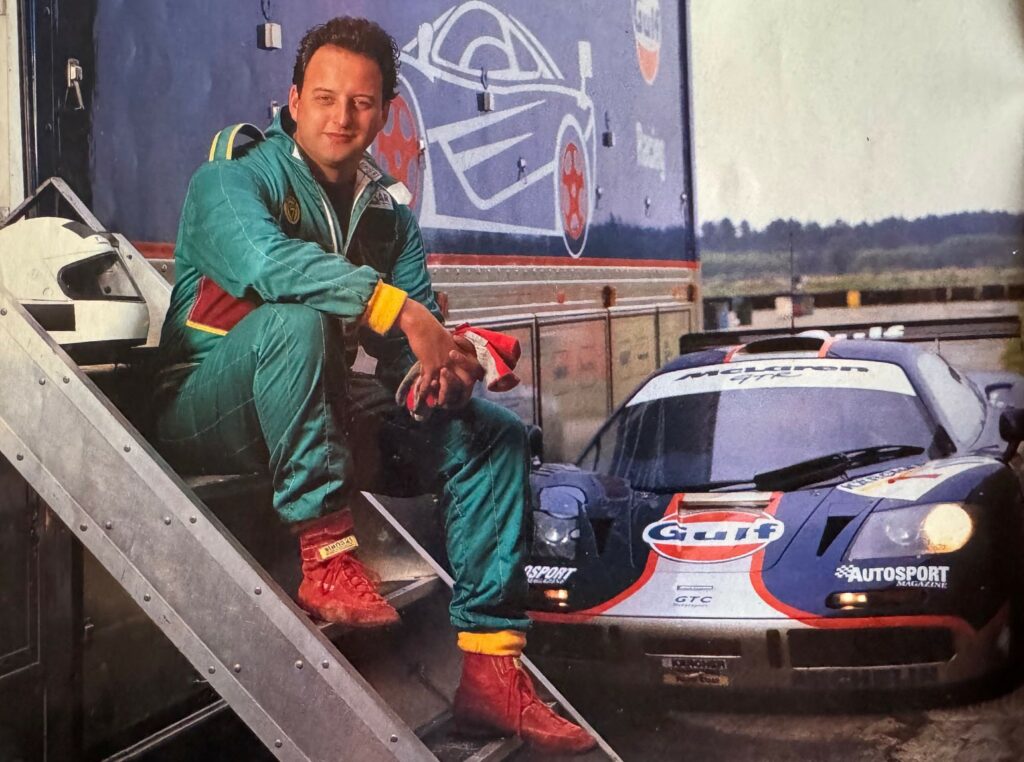

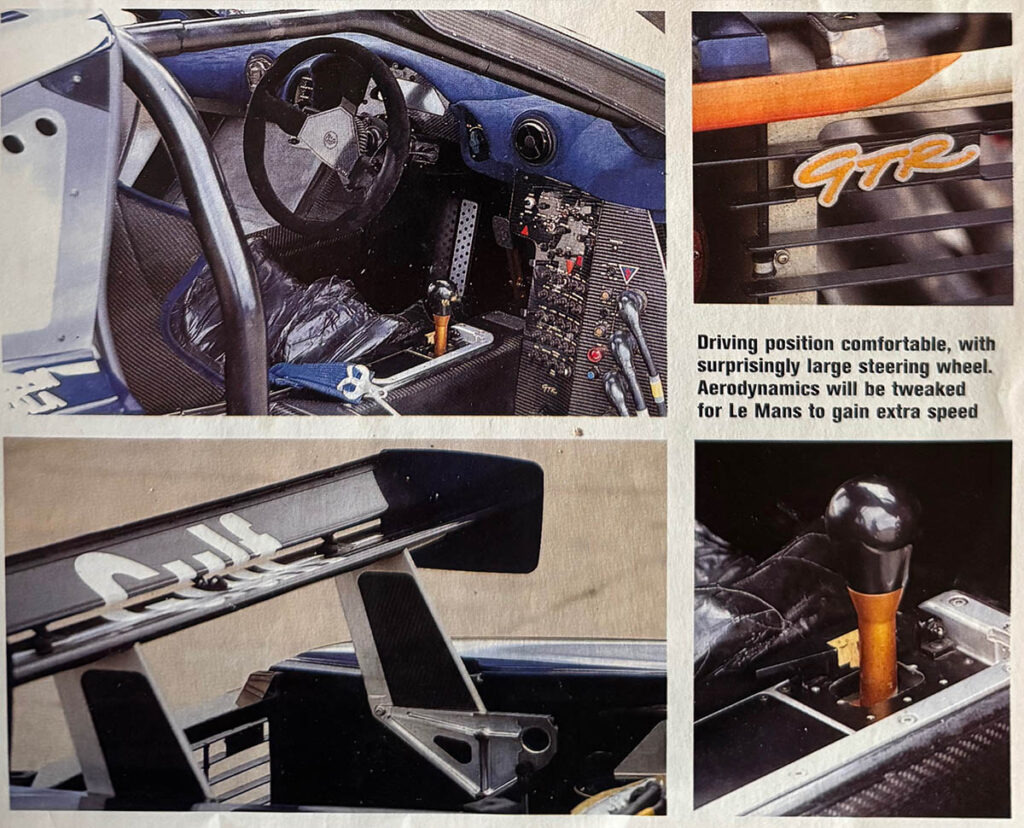

Thirty years ago I perpetrated an absolutely enormous fraud, and to this day I remain slyly proud that I did so, writes Andrew Frankel. I used the fact that I was the road test editor – le plus gros des fromages when it came to car testing – of Autocar magazine to wangle my way into the cockpit of the most hotly fancied of the McLaren F1 GTRs prior to Le Mans in 1995. It was only a few weeks before the race, and this very car, owned by Ray Bellm, operated by Michael Cane at GTC Motorsport and resplendent in Gulf livery, had already won four of the six rounds of the BPR championship held so far that year.

I duly turned up to a test session at Pembrey, and soon found myself talking turkey with one of its other drivers, a certain Mark Blundell. Dressed head to foot in brand-new Nomex duds, I looked the part – and I sounded it, too.

In my defence, I told no lies about my credentials – they just presumed a man in my position would know what he was doing behind the wheel of a slick-shod, 6.1-litre, V12 racing car on a cold, damp track in Wales. My only sin was one of omission, namely to fail to disabuse them of their entirely natural but utterly misleading impression of me. Because if they’d known the truth…

Which was that in my life to date at that time I’d done a grand total of just under 12 minutes of racing, in a 1.4-litre Caterham on the Indy Circuit at Brands Hatch, which I’d driven to the circuit myself. I may have failed also to mention that despite the extreme brevity of that race, I still managed to fall off. I’d never driven anything on slicks in the wet or dry, and could barely find my way to Pembrey, let alone around it.

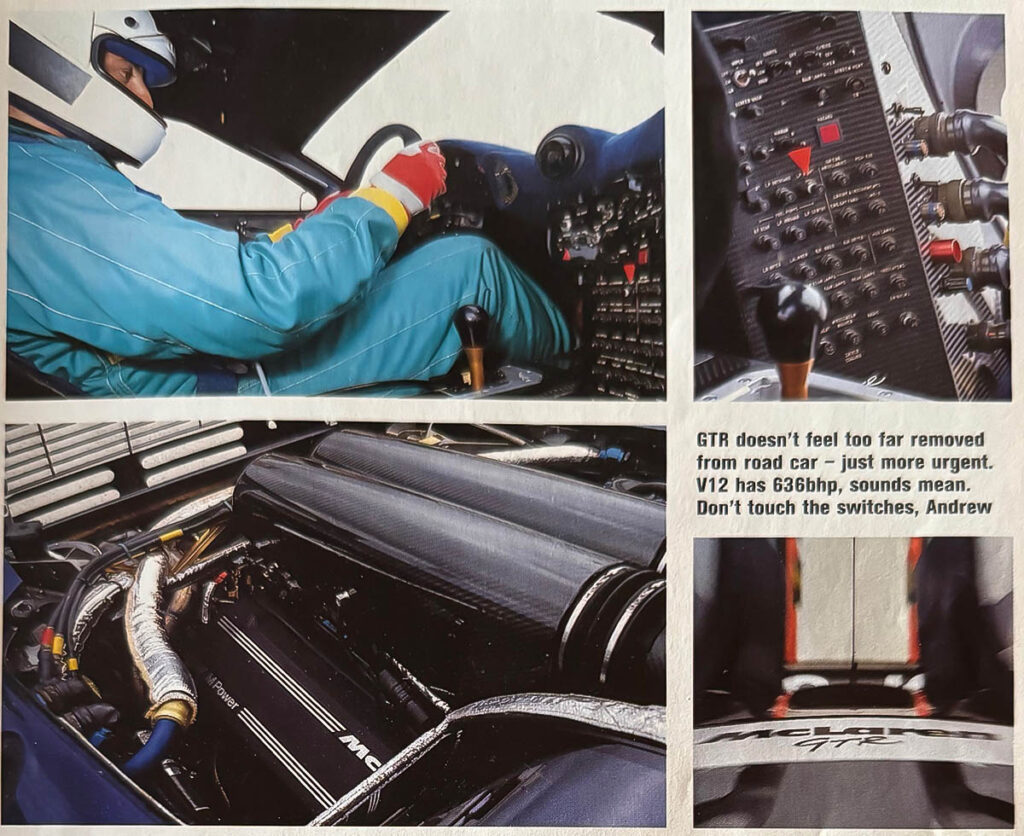

Nevertheless, and to no one’s greater surprise than mine, this was actually the fourth F1 I’d driven, the previous three all being prototype road machines sampled at the time of the car’s first official test drive a year earlier. So with a slightly less powerful engine thanks to Le Mans restrictors, and no great weight loss regardless of a stripped interior (the FIA insisted the car had a full steel rollover structure installed despite the fact this was weaker than the carbonfibre safety cell to which it was attached), the thrust at least would be familiar.

As he always is, Mark was kind and solicitous. He could probably tell I was terrified. He told me not to be worried, to use the torque and to always be a gear higher than you’d expect. All I had to watch was getting on the power too early at the exit of a corner, lighting up what would be at best tepid rear slicks. The team made no secret of the fact they didn’t want me in the car: it was far too close to the race to be taking such a risk, and they had many better things to do with their time. I’m not sure why they agreed in the first place.

All of which I understood, and none of which did anything to allay my rising sense of trepidation as I was strapped into the car and that carbon door was slammed behind me.

The interior was simple, spacious and spare, light years from the Star Wars cocoons of modern Le Mans cars. There was a basic LCD instrument display, a big, round, unadorned steering wheel for grappling with the unassisted rack, and a bank of switches, fuses and relays for relatively easy access by a knackered gentleman driver trying to understand why his F1 GTR has failed to proceed at 3:00am on Mulsanne. I flicked on the ignition, pressed the starter and nearly leapt straight back out the car. Liberated from the suffocating embrace of silencers and catalysts, the noise of the V12 ricochetting off the bare cockpit walls filled all the available space, including that located between my ears. It’s just a car, Andrew; it’s just a car.

Which is what it turned out to be. Today there are Tesla owners who’d scarcely raise an eyebrow at its acceleration, and even to 30-years-younger me it was nothing I wasn’t already fully prepared for. The gearbox was precisely how I remembered the road car’s to be. Only the chassis appeared to have dramatically changed.

Compare a standard F1 road car back to back with a more modern McLaren hypercar such as a Senna or P1 – as I have been lucky to do – and what will strike you most is how softly sprung it is. Not so the GTR. Where the street machine dove and swooped into corners, the GTR darted and flicked. It was alarming at first, but the more I came to trust the car, the more its precision and response actually felt rather reassuring: I may not have known what I was doing, but my car certainly did.

Confidence blossomed until I found myself hammering along, throwing gear after gear at that insatiable engine, and feeling I was even doing a decent enough job in the corners. I thought the team would be relieved, they might even be a bit surprised at the pace at which I was lapping. Sadly not: years later Bellm was kind enough to tell me they’d never seen a racing car being driven so slowly.

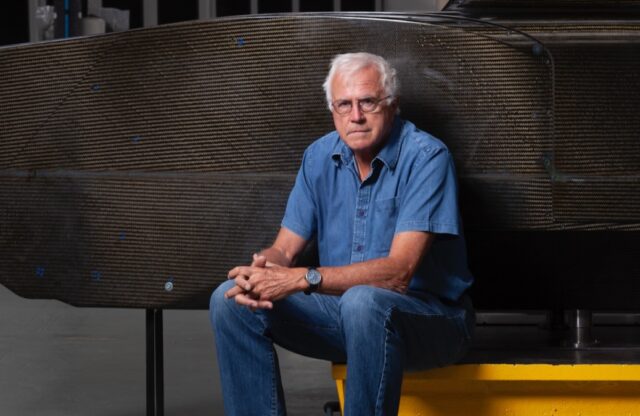

But I didn’t crash it which, on a damp and unknown track, on slicks and with my non-existent level of experience, felt like some kind of accomplishment in its own right. We got our story, too – which is what I’d gone there to do. It was only later when I got to know Andy Wallace that I discovered the early and undeveloped F1 GTR was by no means an easy car, and had to be commanded with great skill and steely composure… not that I ever got close to a point where that was likely to be a problem.

Even so, of the seven F1 GTRs that started Le Mans, two crashed out altogether, while Bellm himself crashed heavily in the car I’d driven, the strength of its all carbon construction being the only reason it was able to continue after lengthy repairs. I finished the story I wrote at the time with the line: “If the just reward for guts is glory, then victory in France is the very least they [the team] deserve for letting me drive their GTR.” Sadly, for this car at least, it wasn’t to be.