The double-takes are hilarious. Perhaps a few of the passers-by feel they sort of recognise it, but generally the looks are of pure confusion mixed with admiration as they take in the wide, low Valour idling menacingly outside a posh hotel in the chi-chi Cotswolds. Except for the Bentley Continental GT driver, who manages to convey “I’ve just been outdone and I don’t like it” in mere split seconds.

But who can blame any of them for the confusion and envy, for they’ll probably never see another example of the Aston Martin Valour in their neighbourhood ever again. It’s a 5.2-litre 715PS 753Nm V12 monster, with a six-speed Graziano manual transaxle and a mechanical differential rather than the sophisticated autos and electronic diffs of every production Aston. Just 110 are being made, each costing more than £1 million, and all are already sold to customers around the world. Thankfully at least one is staying in the UK.

To me, it looks like the car that petrolheads of a certain age would have scribbled on their school exercise books. Indeed, I suggest to design director Miles Nurnberger that he’d done exactly that. I know I did. The Valour grew out of a private commission that spawned the 2020 Victor (and will lead to the more track focussed Valiant), and it plays on the era of the original V8 Vantage and its contemporary European muscle cars, with a bit of ModSports racing madness thrown in for good measure. Who knew a bit of 1970s/early ’80s style could look this good?

“We don’t normally do retro,” says Miles, “but I think with this car it’s not just the look, it’s the era that it sums up, which has become more relevant in the move to electrification: the antidote has become the 1970s and early ’80s.”

As you can see, though, it’s not pure retro, because the design team has mixed in many of the learnings from the recent Valkyrie hypercar and the forthcoming Valhalla mid-engined V8 supercar {“you can’t unlearn that stuff,” says Miles). Take that Kamm tail for example, so redolent of performance cars of 40-odd years ago: beneath it is an array of rear-light tech straight off the Valkyrie and Valhalla, and a diffuser that looks like it came off a GT3 race car. It’s quite a mix!

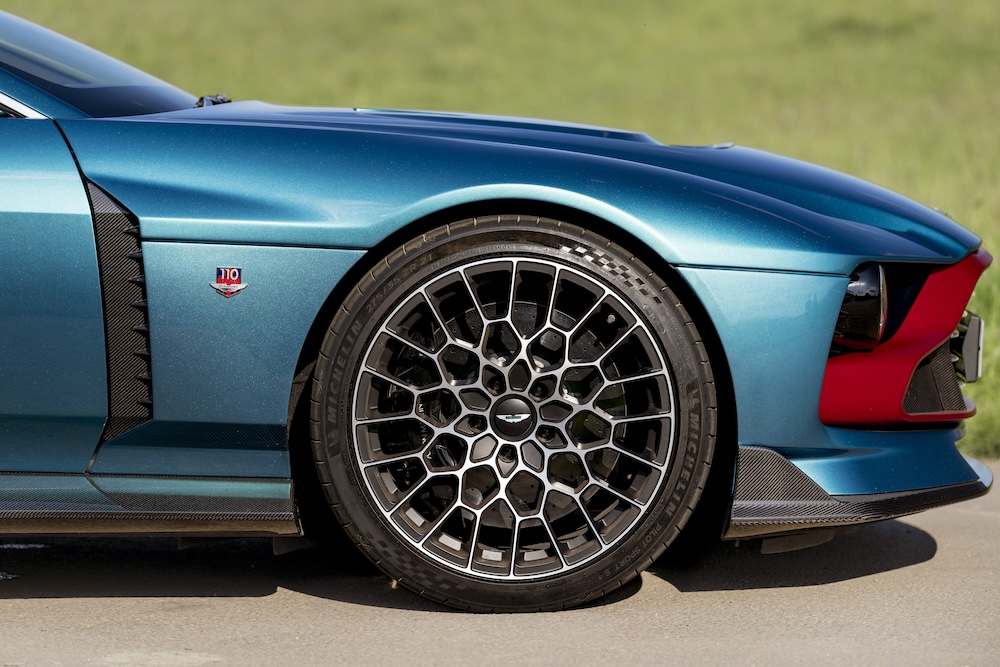

At the other end, we have that aggressive shark nose, made safety-regulations friendly by incorporating a structural bumper under the carbonfibre ‘lipstick’ picked out in red in this car. It’s a neat trick, as is the way the front grille appears smaller – and therefore less current – than it really is. Miles points out that it’s what designers and modifiers would have done back in the era of the V8 Vantage, adding extra grilles and intakes wherever possible. But to that are added touches of the latest aero tech, like the turning vanes on the ends of that low front splitter.

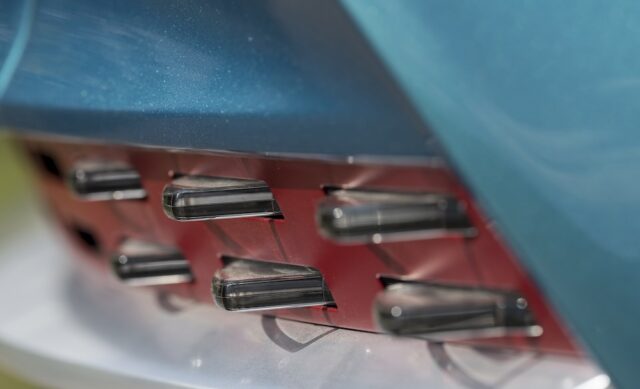

It’s the same with those boxy wheelarches, which the design team refers to as cereal boxes; in period they’d have been added crudely, because the ability to integrate them just wasn’t available as it is now. Or take the most playfully retro feature of all, the faux-louvred rear window, which incorporates little fins that apparently supplement the aero effect of the upturned Kamm tail.

“We tried to be purposely a little bit Neanderthal in the way we did it, and then just refined it at the end to get some of these things,” says Miles. Engineering director Simon Newton backs this up: “From a controls point of view, particularly with the driveline and how that interacts with the dynamics, it’s very analogue. When you get the car into slip, you’re very aware of its mechanical, limited-slip diff and you know what it feels like when you get it locked up. It’s very positive and clear when it does. It’s not the infinitely variable, super-refined unit that we’ve spent a lot of time, money and effort integrating into the Vantage, for example.”

I recall this an hour later, driving the Valour alone in the countryside, listening to the rumble of the exhaust and the faint background whine of that Graziano transmission, feeling the mechanical differential working and revelling in the massive, ridiculous torque propelling this fantastic beast along the curving A-roads so effortlessly. It’s not crude… and yet there is a basic, deliciously dirty mechanical feel to it that’s been lost from most modern performance cars.

Sure, that twin-turbo V12 is deliciously smooth and almost too sophisticated for this car, and its exhaust note is sporty rather than raucous in Sport and Sport+ driving modes (in Track it’s more lairy), but the huge torque delivery means that whatever the gear, whatever the speed, a prod of the accelerator never fails to rocket the Valour forward. The gearbox is remarkable; modern supercars are autos now, mostly because manuals (and their clutches) can’t handle the torque without feeling utterly agricultural, but this is a beauty, with the added bonus of a sensibly weighted clutch, too. For such a brutish car to be so easy but rewarding to drive is a wonder.

It rides equally well, coping with the rough surfaces of British country roads and controlling the power without feeling harsh, as long as the adaptive-damper suspension is kept to its first setting, or the second setting if you’re prepared to put up with a more jarring ride. The final of the three settings is for smooth tracks only; it’s just hard work on the road. So once again, the Valour is more cosseting than it looks.

There are plenty more such entertaining contrasts visible all around me, ensconced in the low, hip-hugging carbonfibre seat. The headline and seat coverings are a gentlemanly tweed, but the gearlever mechanism is exposed to show the greased knuckle joints that link back to the rear-mounted gearbox. That seat can be reclined electrically, yet it needs a tug on a leather tag to slide back or forwards.

The interior door handles are matching leather tags, but the large mirrors are adjusted electrically by controls part-hidden in the door cards. Where there isn’t leather or tweed, just carbonfibre is visible – swathes of the stuff – which can be colour-tinted should the buyer request it. In fact, this being looked after by Q Division, there’s not much that can’t be specced to the customer’s taste.

This car’s spec, though, was chosen by the Aston Martin design studio. It’s even more striking up close than it looks in the pictures, and more subtle, too – surprisingly, with so many neat details to pick out. Even the view out of it is different from the usual, with the creased tops of the front wings in literal sharp contrast to other Astons, and the view of the rear haunches in the door mirrors even more pronounced. Speaking of mirrors, the windscreen-mounted rear-view mirror is actually a screen, fed from a camera in that rear window cover.

There’s a danger that this is making the Valour sound like it’s all about styling, little trinkets to justify the big price tag. That’s not the case. This is more than a top-hat engineering job; even though it’s based on Aston Martin’s familiar aluminium architecture, the underpinnings have been reworked and set up to give the Valour a unique character in the way it handles, steers, rides and reacts to that uprated V12.

Over the past two years I’ve driven the DB11, DB12, outgoing Vantage, last-ever V12 Vantage and new Vantage. This is the one that feels the most special of all, the one that’s the most breathtakingly fast in the dry, the one I’d feel most nervous of in wet weather, the one that will forever conjure up memories of accelerating apparently effortlessly in third gear through long, sweeping bends in some of the UK’s most beautiful countryside. It’s the one that has brought my school exercise book sketches to life in a way that I could never have imagined.