Off the back of a highly successful Goodwood Festival of Speed 2024 for Czinger – the auto manufacturer’s 21C broke the production road car record up the hillclimb, with a time of 48.83 seconds – the company is ready to hit send on its ‘printed’ hypercars. As the 21C and the 21C V Max are readied for production, we sat down with chief designer and company co-founder David O’Connell at Goodwood to get the lowdown on the challenges that process holds, plus what the future has in store for Czinger’s technology and the firm itself.

We learned a lot and improved the car – but the best thing about it was that we were able to accomplish all this and we didn't have to change too much

“For a small team, where everyone wears a lot of hats, it was a huge undertaking,” chuckles David. “They’re dedicated hats, but there are a lot of hats.”

As he and I sit mere inches away from the screech of V10 Formula 1 cars atomising rubber on Goodwood’s famous start line, things are looking good for Czinger. Aside from its in-house cars making their way to the company’s own start line, more established names such as Lamborghini and Bugatti are utilising the firm’s innovative tech solutions.

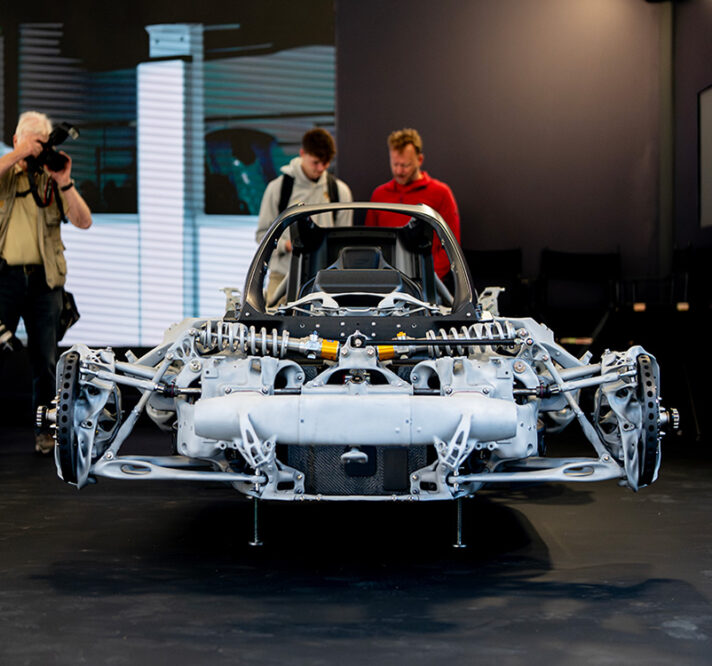

For the uninitiated, Czinger uses generative AI to design structural elements, which is then 3D-printed and assembled by laser-guided robotics. The first two fruits of this labour will be the 21C and 21C V Max; powered by a 2.88-litre flat-plane-crank V8 that’s good for 950bhp and revs to 11,000rpm, matched with a pair of electric motors that boost power to 1250bhp with an option for 1350bhp.

The 21C has a projected top speed of 219mph, but the aerodynamically optimised V Max is gunning for 253mph. The 21C, of which a mere 80 will be built, caused a stir at its UK debut at the Concours on Savile Row in 2022. However, it is one thing to build a fast car, it is another to build one that people can drive, as David explains.

“We brought in safety guys and a regulation specialist, and worked with companies to make sure everything was in place – we now have a car that goes through all the homologation, crash and regulatory processes, not just in Europe but in America and Asia,” he says. “We learned a lot and improved the car – but the best thing about it was that we were able to accomplish all this and we didn’t have to change too much. We didn’t have to make radical design changes for emissions, safety, all of those things.”

The car is now fully crash tested, something that David admits broke his heart a little. “I had to watch it go into a cement wall; that was gross,” he chuckles. The past two years haven’t just been about constructive destruction, however.

“We developed a full range of colour for the exterior and interior of the car – it’s a premium, high-performance brand, so we had to find suppliers that could meet that level of execution we require for the product,” he says. “It was fun, but at the same time the design team were involved at every step of the way, because a lot of small tweaks can really affect the way a car can look. We’ve got to keep our eye on the creative ball so that something doesn’t happen that is detrimental to the aesthetics, which is clean, simple, bold – we call our design language functional art. It’s got to be something that people are excited about, but it also has work – and work really well.”

David is under no illusion that the demands are particularly high in this area of the market, one in which he cites Bugatti, Rimac, Zenvo and Koenigsegg as competitors. Although he won’t be drawn on how many have been sold so far, he’s seeing the split as half 21C and half V Max, although one customer has bought one of each. So far the main source of interest has been from the US, but a small number have been sold in the UK and Germany.

“I think that’s pretty good for a new brand that’s introducing a specialised product,” he says. He’s expecting further sales now that production-specification cars are available to be seen, and a dealer network and serving support team is in place.

However, the Czinger business model is about rather more than its own hypercars. Czinger’s parent company, Divergent, has recently confirmed a relationship with McLaren, and it already has programmes in place with Aston Martin, Lamborghini, Mercedes-AMG and Bugatti – the new Tourbillon uses Czinger technology in its construction.

“It’s interesting: as I sit here [in the Supercar Paddock], I see people come up and know who [we are], and spend a lot of time looking – this is something we want to share and expand, and make a part of our business model,” he says. “Execute these really beneficial structural parts to other companies so they can reap the benefits – the lower cost, the shorter lead times, the flexibility, the stiffness, the lightness – all the attributes that makes the Czinger really different.”

David views the Czinger as an entirely new kind of car thanks to its DNA, the way it’s put together and the core construction process – however, he’s well aware that technology within the sector moves fast.

“The progress we’ve made in two years, from a structural point of view, that’s going to continue. As printer speeds, build volumes and efficiency increases, we’ll be able to print bigger components faster – subframes, wheels, brake [discs] integrated with calipers,” he says. “That’s what this company is about – innovation. The only thing limiting printers at the moment is the speed of the lasers and the build volume, but if you look at where we were five years ago and where we are now, and if you project that curve into the future, it’s pretty exciting what we’ll be able to do.”

David points to other applications for the technology, particularly combining two functions or elements into one part. “You can have fluids that run inside the part so you don’t have to use extra hoses – you can do really wonderful things that reduce part count, which makes things simpler for everybody.”

The other major benefit is lightness, he says. “The lighter the car, the better, and we’re not sacrificing any of the stiffness or structural performance.” Although he won’t be drawn on a precise weight figure, he says it’s a little bit north of 1250kg. While the printing technology is being used on the complex metal structures, the car is based around a carbon tub.

Of course, the carbon-tub concept is very expensive to produce, and has rarely been used out of the £100,000-plus hypercar market – how long will it take for printed technologies to make their way to ‘regular’ cars?

“I come from a background of working for big car companies that are resistant to change, which I totally understand because of the systems they have to make work,” David says. “However, if you stay in one place too long your feet sink into the sand and you can’t walk. So I’m hoping that as we show our accomplishments with what we’re doing at Czinger, our partners and clients will integrate the parts into their cars, and it’ll trickle down the line.”

He points to the efficiency and potential for cost savings. “The footprint of our assembly process is one-tenth of a conventional stamping plate, and with large-format printers you can produce a high number of parts on one build plate, shingling and nesting them together – so you don’t have to pick one part,” he says.

While Czinger is focused on its 80 21C and 21C V Max, and building those, thoughts are already forming about the next project. It’s in the early stages, and the method of propulsion has yet to be settled upon – not that David sees this as a major problem.

“The technology allows you to be ‘powertrain agnostic’ – the flexibility of the manufacturing system allows you to have a subframe that carries a total EV version, or an internal-combustion engine. You’re not tooling two entirely different chassis – you’re printing one subframe, and then another,” he says.

“All powertrain technology is improving. I drive an EV, and the range is great, unbelievable compared to what it was five, three or even two years ago – it’s fun to drive, but maybe too quiet.

“At the same time, nothing much can replace the sensory pleasures of ICE, and ICE units have become more efficient than they were; smaller and more powerful – there are good things out there.”

Despite the challenges the wider automotive industry faces, David is positive about the future. “I think we’re living in a really good time of intelligent automotive design. Cars have become a lot better in the past ten, 20 years, and consumers at every level have become smarter,” he says. “I think we’re living in a really nice renaissance time for automotive development.”

Find out more about Czinger here.