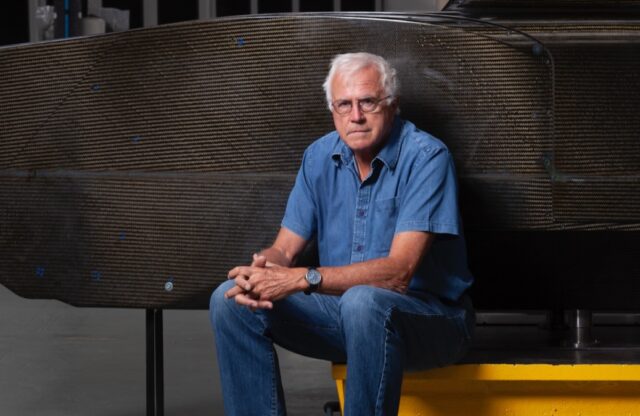

Words and photography: Alain de Cadenet

Alain de Cadenet, who has passed away aged 76, wrote this superb article for Magneto magazine in 2021, recalling meeting Campbell in 1966 and then, 20 years later, being a part of the BBC TV film Across The Lake, starring Anthony Hopkins. The photographs here are Alain’s from filming at Coniston Water.

Destiny, by definition, is what will occur to a person in the future, determined by previous events. Some believe that it is all beyond human control. This is perhaps when fate tangles with destiny to produce undesirable results. Donald Campbell CBE (1921-1967) certainly qualified as a man with a destiny. He knew from an early age, having witnessed his father Sir Malcolm Campbell pursuing his racing and record-breaking career, that he would be following in those footsteps.

During 1966 I was taking on consignments as a freelance photographer in an attempt to pay for motor racing. It’s hardly surprising that when I was asked, in late October, whether I’d like to go up to Coniston Water to take some pictures of Donald and his Bluebird K7 jet-powered boat, I couldn’t wait to get there. I jumped into my race car, the ex-works demonstrator AC Ace-Zephyr. With enough space in the boot for my borrowed Hasselblad and lenses, plus my trusty Leica III and a few rolls of film, it doubled as my daily transport.

I got to the Sun Hotel rather late and checked into the only room available – which was furnished with a stiffly sprung ex-army bed. I was amazed to find that Donald’s team of helpers were, mostly, more of a family of useful dedicated workers rather than pure professionals. Leo Villa, master mechanic and fixer, who had of course orchestrated all of Sir Malcolm’s numerous attempts to set world records on both water and land, was in attendance and very much in charge. He and Donald already had seven Water Speed Record attempts under their belts, with the most recent at 276.33mph taking place in Western Australia on the last day of 1964. Donald had also achieved the world Land Speed Record in Western Australia on the Dumbleyung salt lake the previous July, thereby becoming the only person to reach both milestones in the same year.

Seeing K7 under its makeshift awning at Coniston, watching the team at work and being shown around the encampment was the most inspiring thing I’d ever seen at that time. K7 was comparatively naked; unclothed enough to see through open panels into the Orpheus engine bay. Initially designed by the Norris brothers Ken and Lew for a lesser-powered Metropolitan-Vickers Beryl gas turbine, the craft had recently been fitted with a Bristol Siddeley Orpheus from a Folland Gnat that produced a good 20 percent more thrust.

I duly completed my photographic task, and spent some time over lunch talking to Donald. What I learned was that his whole team totally believed in what he was doing, and that the record could and would be broken. It would need clement weather and attention to every detail for success. I also learned that record breaking was something that, once started, was all but impossible to stop. Donald was the most patriotic man I’d ever met, and utterly pragmatic about the task in front of him. I subsequently discovered that he was highly stressed out by the press and others continually harassing him to ‘get on with it’. None of which helped.

There was also the cost factor. He was in need of success to carry on. I suspect he could find a little peace only when he climbed into his Bluebird Blue Jaguar E-type and headed off for a drive around the lake. It’s difficult to be phlegmatic about the job when you are surrounded by emotion, pressure, well-wishers and a rookie with a camera asking daft questions.

You know what happened next. January 4, 1967 was the worst day. Donald’s initial run went well and he was clocked at just under 300mph on the out run. Anxious to get the record achieved, he opted to do the return run without either refuelling or waiting for the surface shock waves to completely subside. With just a few hundred yards to complete the run, the Orpheus jet likely flamed out, which resulted in the fatal crash.

What I had learned in the couple of days I spent at Coniston was instrumental in how I then tried to go about running my own racing activities. The idea of having an all-British racing machine started to appeal, even if the first effort with a home-made Martin V8 stuffed into a Diva Valkyrie didn’t work. As with Donald, one just keeps at it until the team around you believe in what you’re trying to do. Together, you get the job done.

But imagine my surprise 20 years later when filmmaker Tony Maylam asked me to construct a life-size replica of K7 for a forthcoming BBC TV movie to be made about the last 60 days of Donald’s life. Tony was to direct Across The Lake, written by Roger Milner, who had also written BBC’s The Speed King about Sir Malcolm’s life. Tony had signed up Anthony Hopkins to play Donald.

Fortunately Jack Lovell, who’d cast all of my prototype racing-car bodies in glassfibre in his Battersea premises, had also worked in the movie industry. He was more than confident that he could get this built. Armed with photographs, films and copies of the original drawings, archived in London’s Science Museum, he commenced the reconstruction of a movie version of Bluebird K7.

Initially, a small model was made of one half of the boat, to give an accurate three-dimensional impression of the complete craft. Full-size cross-sectional drawings were created and pasted onto plywood, and then cut to size with a bandsaw and jigsaw. These sections were then assembled onto a wooden keel to give an outline overall shape. They were then covered with lath-like strips of wood, and plastered over and styled to the original finish. The BBC was most particular about the detailing, because every rivet had to be accounted for on the original buck. The sponsons on our drawings were the 1955 style, and we needed the 1966 version, which were different. Several days of consternation and midnight oil were burnt altering them.

With the major constituent pieces now prepared, Jack and his crew put it all together – and we had our life-size K7 replica. Moulding came next, after hours of rubbing down and release waxing to ensure the moulds would come off smoothly. GRP panels were produced from these moulds and gel coloured with the correct Bluebird Blue pigment supplied by the same firm who’d made the paint for Donald. The boat was then bonded and screwed together with marine-ply floor and cockpit reinforcement.

The see-through canopy was tricky to reproduce. The only specialist that could do it had produced the Harrier Jump Jet canopies, and it worked with 3/8in polycarbonate. It did a brilliant job, even informing me that I might like to know the unit was bulletproof and virtually indestructible.

The new ‘Bluebird’ had her first airing in the studios of Blue Peter, and thence went to the London Boat Show, where she had a whole stand to herself. We then fitted the two power units. Firstly, the full-size replica of the Bristol Orpheus jet engine, which fitted in just behind the cockpit. This was followed by the actual motive power unit, which was a 200bhp Mercury V6 outboard fitted on the transom into its own well. It was connected via cables to the steering wheel, which had its own starting button and ignition in the cockpit.

‘D-Day’ for launch approached, and the site chosen was the Princes Water Ski Club lake at Feltham in Middlesex. Movement and floatation tests were carried out with the help of 28lb stage weights to achieve the correct trim line. Plenty of tubes of silicone RTV were needed to seal leaks, and expanded polyurethane gave buoyancy around the engine bay.

Coniston Water in February can be very unpleasant indeed. Cold, windy conditions with snow and hail are the norm, and

Maylam was quite apprehensive about his chances of keeping to schedule. However, the production was blessed with the best weather any of the locals could remember. We all felt that Donald was up there, ensuring the right buttons were pressed to help us.

The props department had faithfully recreated the boat ‘house’, launch rails and ramp, and our ’Bird was on her trolley for the press launch on time. Anthony Hopkins came out to meet the media in his blue overalls, RAF-style flying helmet and oxygen mask. Everything was so convincingly represented that one observer, who’d been there for the original run, said it could have been 1966 all over again.

The following four weeks saw our creation working hard for her money. Not just for static shots, but on the move for several hours. Some of the techniques used to achieve results were novel for those very much pre-digital and CGI times. Other than fuel, the only consumables were more tubes of RTV and plenty of hot tea.

Recreating Donald’s exact motions from that fateful day felt eerie. No more so than when I had the ’Bird at the end of the lake in the original start position. I looked through the canopy and saw what Donald had seen; the long expanse of water that stretches away

into the hills at the southern end of Coniston Water. The order to start the engine and give it full throttle came through my headphones. But I was mesmerised.

I suddenly realised what it was all about; it was all very emotional. I told Maylam afterwards that it was perhaps just as well that I didn’t have a live Orpheus in the back, because I would surely have wanted to do a run for real.

And that’s knowing once you start, you can never stop. Donald Campbell lived a life on the edge, determined in his own bloody-minded way to get the job done. Just looking at the Pathé news footage of K7 flat-out on the lake, over 300mph, with only its three points skimming the water surface in the most delicate balance, is evidence that he was right. Perhaps it compares with the Charge of the Light Brigade. The survivors had to know it could have been done, too.