Buoyed by the success overseas of its Fairlady 2000 roadster, Datsun knew that a small, six-cylinder sports car would take the US by storm. Brit marques, including MG and Triumph, had the four-cylinder market sewn up, while six-pot offerings were the preserve of Jaguar and Porsche (with a price tag to match).

Domestic sales, unfortunately, weren’t that impressive for either the Fairlady or the exquisite Silvia. Teiichi Hara, head of Nissan’s engineering and development team, knew that US dealers were crying out for a faster six-cylinder coupé to undercut European marques – and that senior exec Yutaka Katayama, head of the firm’s North American import and sales division, wanted a sports car tailored to US tastes.

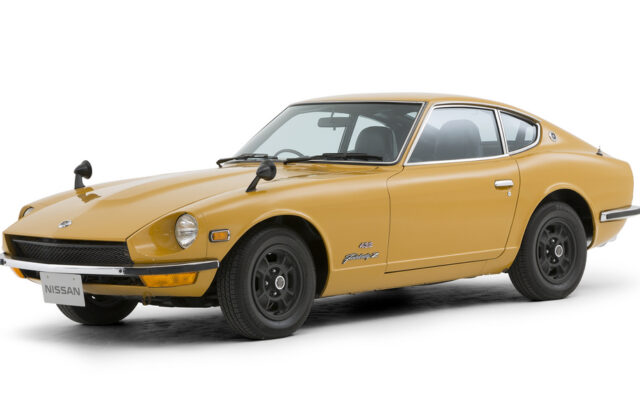

Katayama and Hara created a new Sports Car Design Studio in 1965, installing arch sports car fan Yoshihiko Matsuo as its head. By 1967 Matsuo had started to produce clays that were winning fans within the company – and management approved the new car for production in November that year. After a gruelling 12-month test programme in the US, the Datsun 240Z – otherwise known as the Datsun Fairlady Z – went on sale in October 1969.

Pitched against tough home-grown competition in the UK, the 240Z, despite its sophistication, was not the bargain it was in the US. Import taxes pushed its price beyond £2000, whereas the likes of the MGC, Ford Capri 3000GT, Reliant Scimitar GTE and MGB GT V8 made for a packed marketplace.

Safety legislation, and demands for more space from US buyers, caused the 240Z to pile on the pounds; by 1973, the heavier and more powerful 260Z had taken over across the Atlantic and in Japan. It would be the following year before UK buyers got the wider-tyred, stiffer-sprung 260Z, which was offered not only as a two-seater but also as a 2+2 coupé for the first time. With a foot-longer wheelbase than the 240Z, and a modified roofline, the 2+2 gave rear passengers 33 inches of headroom – but the sleek lines of the Matsuo 240Z had gone.

The Z also inspired ex-Broadspeed engineer Spike Anderson to begin tuning the 240Z (and latterly the 260Z) for fast road, race and rally use. His modifications were sold under the deliberately mis-spelled Super Samuri nameplate to avoid litigation; Samuri Motor Company converted around 74 cars in period.

ENGINE AND GEARBOX

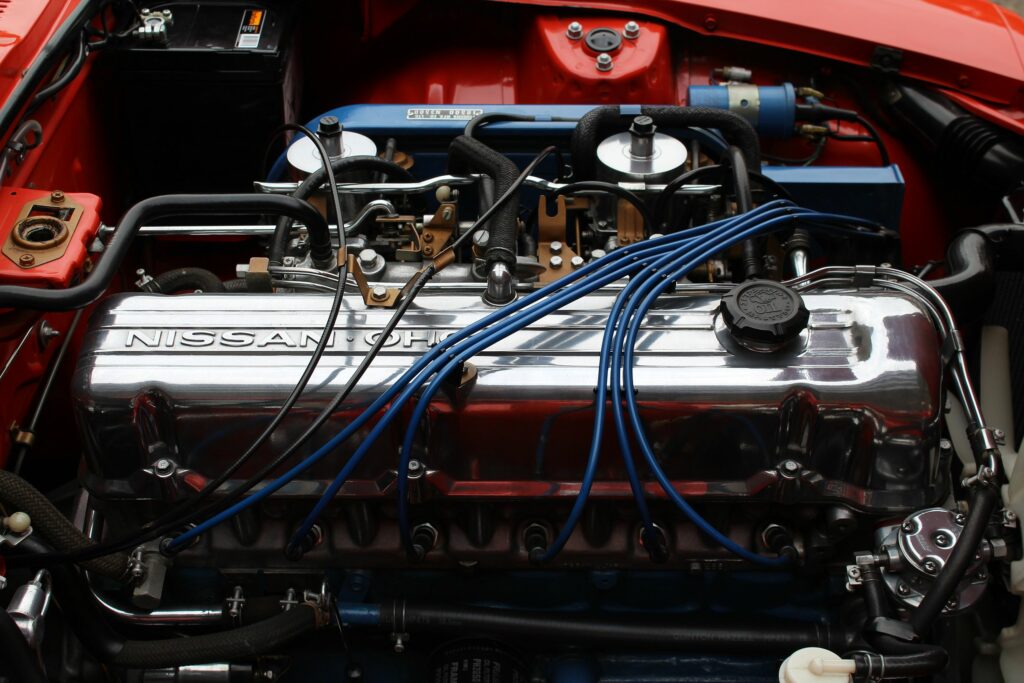

Z specialist Fourways Engineering (www.fourwaysgroup.co.uk), based in Kent, is well versed in keeping 240Z and 260Zs on the road: “It depends what market the car is from,” says technician James Carter. “An imported US model will have a four-ratio gearbox [the five-ratio ‘box didn’t go there until 1977, when it was fitted to the 260Z], whereas a British or Australian car will have a five-speeder, which are better.”

As with the 2.4-litre L-series engine, both four- and five-ratio units have few weaknesses, and they develop problems only if used without maintenance, or abused. Make sure decent coolant or antifreeze has been used; the Z’s alloy head does not appreciate being run on plain water alone.

“We do rebuild these engines, but it’s mostly down to age,” James says. “The powerplants have no inherent problems, and they’re very tuneable.”

Stateside Z models rapidly got more complicated with emissions controls; UK cars kept their licenced SU carburettors, built by Hitachi, which give few issues apart from requiring regular maintenance and adjustment. Parts are hard to source, so many owners upgrade to Weber equivalents, with better spares support.

It’s also not uncommon for 240Zs to be fitted with later, torquier engines from the 260Z and 280Z (“blocks are a nut-and- bolt swap,” says James) or Skyline series – but make sure the work carried out has been declared to the insurance company and done to a good standard.

SUSPENSION AND BRAKES

The twin-pot-caliper front disc brakes give few issues in service; again, upgrades are common, with Z32 300ZX and Skylines being donors.

“Upgrade kits are also available off the shelf,” says James. “They are softly sprung and damped as standard, but coil-over upgrades are easily available.”

Try to drive both a standard and a modified car to see which you prefer; if you want to keep the suspension and brakes as Datsun intended, rebuild kits and spares can be tracked down. Bushes and dampers wear out in the course of service, but again, these are available. Carefully check to make sure mounting points, especially around the front crossmember, haven’t succumbed to rust.

BODYWORK AND INTERIOR

“They rust everywhere,” James says. “Because of the values of the cars now, restoration isn’t uneconomic, however.” While Fourways makes some body panels of its own, such as floor panels, radiator supports, rear valances and sills, front wings are near impossible to source new nowadays, save for a new-old-stock discovery in a dealership or warehouse.

As with front wings, bonnets, tailgates and doors will have to be sourced used, but there is a reasonable market for replacement panels, particularly in the US: “We’ve probably got eight or nine bonnets in stock,” James says. “But getting larger parts over from the US can get quite painful in terms of postage.”

Other rot-spots worth checking are around the arches, the front crossmember (a downfall of many a UK-based 240Z come MoT time), inner wings, suspension turrets, tailgate-closing aperture and corners of the hatch bootlid itself.

“These cars had the bare minimum done to keep them roadworthy when they were worthless,” says James. “Now that they’re valuable, we are having to undo a lot of this work.”

He continues: “You can buy most of the interior new from the US, including door cards, seat foam and seat covers, as well as transmission-tunnel vinyls.”

Dashboards, particularly on US imports, can crack, but these can be repaired or replaced; repro left-hooker items can be bought off the shelf, yet RHD equivalents will need to be revived or changed.

WHICH TO BUY

James would plump for a 240Z over any other HS30-chassised car: “It’s the earliest incarnation of the Z car, and is the most desirable. The 260Z, however, had those few more years of development, and you could argue that it’s a better car.”

Contemporary magazine road tests, while admonishing the 260Z for putting on weight, praised its extra roadholding borne of wider, stickier tyres. They added that the 2.6-litre engine produced a greater spread of torque over a wider rev range than the earlier 2.4-litre unit.

Don’t discount the 260Z 2+2, either, if you’re planning to take family and friends in your new purchase. While the market views these cars as the least desirable (within the remit of this guide) they have two rear seats; the 240Z and 260Z Sports/2-Seaters are just for those up front.

WHAT TO PAY

UK (1972 240Z Coupé)

FAIR: £19,100

GOOD: £25,400

EXCELLENT: £35,000

CONCOURS: £49,000

US (1972 240Z Coupé)

FAIR: $10,100

GOOD: $24,400

EXCELLENT: $55,800

CONCOURS: $86,100

SPECIFICATIONS

2.4-litre inline-six (240Z)

Power: 151bhp

Top speed: 125mph

0-60mph: 8.0 seconds

Economy: 25mpg (est.)